Steve Blake and John Stanaway’s book Adorimini is a comprehensive, detailed, well-written, and beautifully produced history of the 82nd Fighter Group. The 82nd, equipped with Lockheed’s P-38 Lightning, served under the 12th and 15th Air Forces in the Mediterranean Theater of War, and was credited with 548 enemy planes destroyed, 88 probably destroyed, and 227 damaged. In terms of the Group’s losses, Adorimini lists the names of 267 casualties, comprising men who were killed in action, missing in action, prisoners of war, or who lost their lives from other causes. As mentioned in the book’s appendix, these figures indicate that 41% of the Group’s pilots became casualties.

Among the 267 are nine men who evaded capture. These include 2 Lt. Earl T. Green, 2 Lt. Clayton A. Bennett, 2 Lt. Stephen A. Plutt, 2 Lt. Edwin R. English, Jr., 2 Lt. Walter T. Leslie, 2 Lt. John N. Girling, 2 Lt. Elwood L. Howard, Capt. Charles King, and 2 Lt. Lawrence W. Zellman.

Certainly all of these men had a “story”, but, as in “life” – “in general”, for all people – not all stories are recorded. Not all stories that have been recorded are known. And, not all stories that are known, are remembered. But, at least two such stories of men mentioned in Adorimini – stories of survival upon the thinnest margins of probability and luck; stories of endurance and fortitude; stories of courage – are known, and are here presented.

The aviators in question were Bennett and English, both shot down on combat missions in 1943: Bennett on October 8, and English on December 6. Reference to Bennett’s survival, and a compelling excerpt from an account about English’s experience are given in Adormini. These follow below:

2 Lt. Clayton A. Bennett

Most of the missions tended to be escorts of B-25s to targets in Greece and Albania throughout the first half of October. On the 8th the 95th and 96th Squadrons escorted the 321st BG once again, to Athens’ Eleusis Airdrome. As the formation left the target, a dozen or so Me-109s from III and IV / JG 27 attacked the 95th from above and behind, utilizing the cloud cover to their advantage. A running fight then ensued over the Gulf of Corinth.

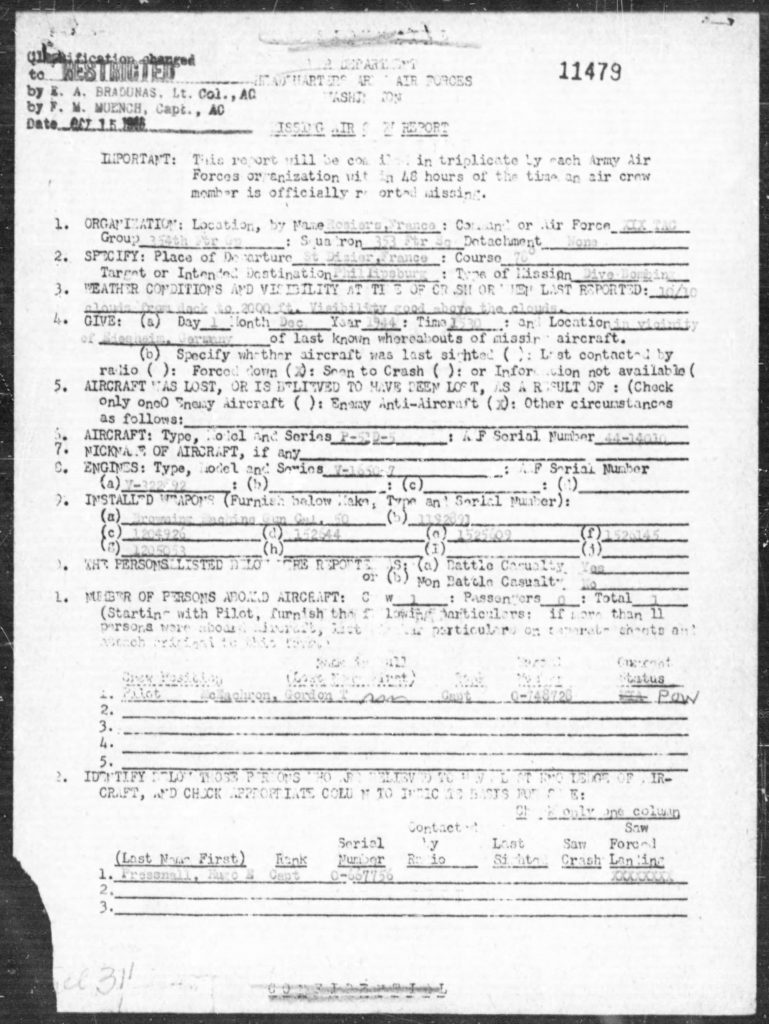

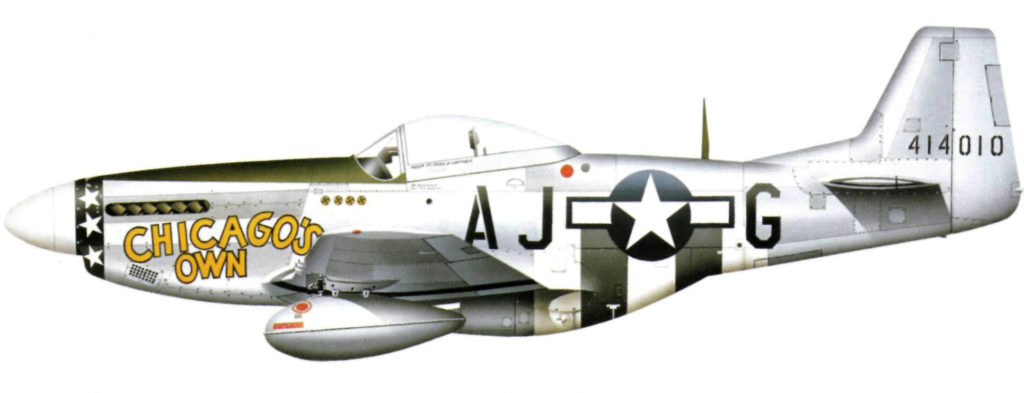

Lts. Bob Muir and Stoutenborough each claimed an Me-109 destroyed and other 95th pilots claimed four more as damaged. Two of the squadron’s P-38s were lost in return; one was seen to crash into the hills west of the target and another fell in flames into the gulf. The latter was flown by Lt. Clayton Bennett, who miraculously survived, although badly wounded. He was also fortunate enough to be rescued and assisted by Greek Partisans. Bennett made it back to Italy in February and soon thereafter was on his way home. The other pilot, Lt. Jim Shawver, was MIA. JG 27 pilots claimed to have shot down eight (!) Lightnings for the loss of one Me-109 and its pilot plus serious damaged to another. (p. 111) (Lt. Bennett was flying P-38G 43-2332, which carried the squadron code “AJ“. His loss is covered in MACR 925A.)

***

2 Lt. Edwin R. English, Jr.

The 82nd returned to Greece on December 6, escorting Liberators of the 98th and 376th Bomb Groups to Eleusis Airdrome. Enemy fighters intervened and the 97th Sq. claimed two destroyed – an Me-109 by Lt. Bill Clark and an FW-190 by Lt. Gene Chatfield, who was on his first mission (!). The 96th claimed 2-1-1 109s, both of the confirmed kills being credited to Lt. Leslie Anderson. (IV / JG 27 lost two of its Messerschmitts that day.) For Lt. C.O. Seltz of the 97th this mission was the magic #50.

The mission was #18 for Lt. Edwin English of the 96th Sq., for whom it was at least equally memorable. He was the only 82nd pilot lost that day. In a report filed after his eventually – and almost miraculous – return, English recalled that he didn’t see any enemy fighters until the American formation was coming off the target:

It was then that I saw 3 ME 109s coming down on the tail of the last group of bombers; I called them in to Andy, and we turned back. To my surprise, we found at least 15 to 20 enemy fighters coming in from above us, by twos and threes. Andy turned into two that were coming in on our left, so Dolezal and I broke off and turned into two that were coming at us from in front, leaving him and his wingman to take care of the ones from the rear.

One of our two started down, with Dolezal after him; the other made a head-on pass at me. My gunsight was flickering, so I turned it off, and fired steadily by my tracers as we closed. Apparently I was hit just as we made our range, for I noticed smoke in the cockpit, but I was too busy to give a damn just then. I started hitting him just as we got in range, with my tracers pouring in, and he pushed his nose down to dodge; I kept them on with forward pressure, and saw cannon shells explode in his engine, with pieces flying off his plane; as he passed fifty feet below me.

I could see the pilot slumped ever to the side of the cockpit. I made a quick break to the left, and saw him start straight down, smoking heavily; I watched him fall straight down for 5,000 feet, and would have followed, but there were too many planes around. So I broke to the right and picked up Dolezal again; we started a two ship weave back towards the bombers, when I found that I was on fire. I noticed that on the leading edge just inside the right engine nacelle was a hole the size of my fist; a 20 mm shell must have exploded in there, and it was rapidly getting worse.

I tried to turn off the right engine gas, but the valve was jammed; I cut the mixture control, stopped the engine and feathered the prop. I saw I couldn’t get up under the bombers, and as there were still a number of fighters around, I decided the best thing to do was to hit the deck and get away, so I called Dolezal and said I was going down. I peeled off and went straight down, pulling out on one engine at close to five hundred miles an hour at about 1500 feet over the plains, and heading west for the mountains pulling 40 or 45 inches on my left engine; nobody was following me.

I thought the fire might blow itself out so I could get home on one engine, but by the time I made the mountains the fire was much worse, with the hole in the wing two feet wide and three feet long, burning fiercely; there was so much smoke in the cockpit that I couldn’t take off my mask. I cleared the top of the mountain at tree top level end saw a nice little valley ahead of me where I thought I might be able to land.

Someone called me, asking if I was all right; I answered that I was on the desk with one engine on fire and that I might make it; I repeated this, and someone asked my heading; I told them northwest. But just as I cleared the mountain, my left engine started cutting out, and I stalled out in a spiral spin to the right, the piano being at a 45° list to the right, and about 45° nose down.

I was plenty close to the ground, so I had to get out, and soon. I called “I’m bailing out,” grabbed the emergency canopy release and started out, but forgot to release my safety belt; I unsnapped it, put both hands on the top and pulled myself up; maybe I even jumped up and out, but I’m not sure.

I have no idea how I went through the boom, as I went straight out the top without rolling down the windows; I probably went over it. My air speed was then about 110 or 115, just above stalling, having lost my speed in clearing the mountain top. The wind and flame hit me at that instant, and I threw my hands up to protect my face; after I was out of the flame, I grabbed for the rip cord, missed it, and got it the second time. I tore off my mask and helmet, which were afire, saw the around coming right up at me, end just had time to reach for the shroud lines and pull my feet up when I hit.

Luckily, I landed on the slope of the mountain aids and broke my fall; I rolled about ten or fifteen feet down the hill, getting all tangled up. I immediately got untangled and out of my chute, for my plane crashed and exploded about 100 yards downhill from me, pointed up hill, and the guns started to go off right in my direction. I ran down past the plane. My flying suit had been burned off, with my escape kit and escape purse, and I later found that the bask strap of my harness was burned nearly through and my clothes covered with the white stuff that the nylon of my chute burning left on me, so I guess that I had a mighty close shave.

“A might close shave,” indeed! Lt. English’s luck continued to hold, as he was assisted by some nearby shepherds, who turned him over to members of the Greek Resistance. The latter took him to a hospital, where his burns were attended to, after which he recovered rapidly. Later English and some other American and British evaders were escorted by foot to the east coast of Greece, where they boarded a boat for Turkey; they eventually made their way to Cairo via Syria. He was back with the group by the middle of February and was sent home shortly thereafter. (pp. 123-125) (Lt. English was flying P-38G 43-2531, with carried a squadron code of “B10“. His loss is covered in MACR 1469.)

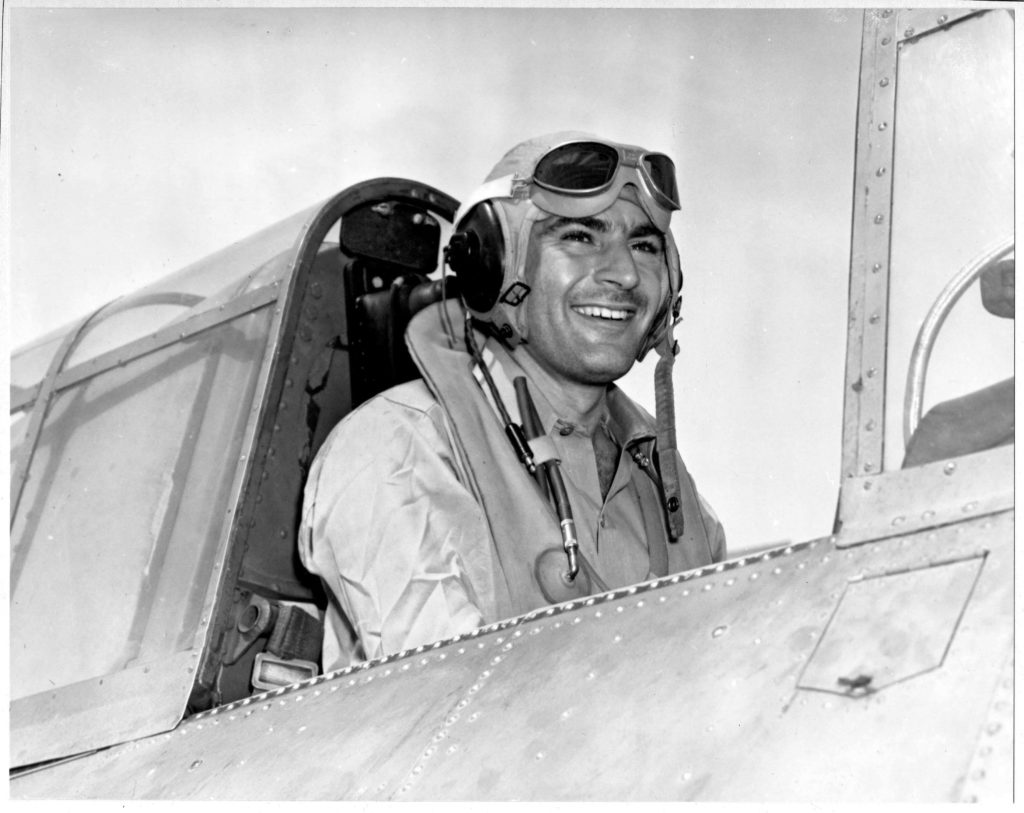

The above photograph, from Adorimini, shows a group of 96th Fighter Squadron pilots prior to a combat mission. According to the caption, the men are (left to right): Lt. Art Larkin, Lt. Jim “Never Nervous” Nuckols, squadron intelligence officer Lt. Bob Cutting, Capt. Dan “Mac” MacDonald, and – lastly – Lt. Edwin English himself.

To gain an appreciation of the nature of Lt. English’s experience, I’d like to direct the reader to the Nathaniel G. Raley collection, at the Veterans History Project of the Library of Congress. Lt. Raley, a 1st Lieutenant, was also a P-38 fighter pilot and member of the 14th Fighter Group’s 48th Fighter Squadron. Shot down over Italy on February 10, 1944, he – too – survived a very (very) low-altitude, last-moment bailout, after his fighter has been struck by ground fire. (P-38G 42-12962; MACR 2306) Captured, he was imprisoned by the Germans at Stalag Luft I. Mr. Raley’s account, which is presented in two video interviews, is detailed, moving, and enlightening, especially in terms of Mr. Raley’s experiences as a POW in Italy and his postwar reflections. It is available in two sections.

***

However – !

While reviewing my files, I found a document comprised of the reports given by Bennett and English to Captain David Weld, a 15th Air Force Intelligence Officer, upon their return from Greece. (Also included is an account by Lt. Walter T. Leslie, shot down during the mission of the 1st and 82nd Fighter Groups to Ploesti, on June 10, 1944.) This document was copied during a visit to the Albert F. Simpson Historical Research Center at Maxwell Air Force Base, in 1986. The accounts are riveting and detailed, especially in terms of their experiences while recovering from serious injuries with limited medical resources, living with Greek Partisans and civilians, evading capture by the Germans, and returning to Allied control.

Having not seen these reports elsewhere, I thought it would be worthwhile to share them with a wider readership. Accordingly, I’ve transcribed the accounts in a format and font style (Times New Roman) as close as possible to the original document, and have created this post to make them freely available.

Escape and Evasion Reports for Clayton A. Bennett and Edwin R. English

– References –

Blake, Steve, and Stanaway, John, Adorimini (“Up and at ‘Em!”) – A History of the 82nd Fighter Group in World War II, The 82nd Fighter Group History, Marceline, Mo, The Walsworth Publishing Company, 1992.

Rob Brown’s RAF No. 112 Squadron website includes pages devoted to each Fighter Group in the USAAF’s 12th and 15th Air Forces. The website for the 82nd FG can be found at: http://raf-112-squadron.org/82ndfghonor_roll.htm