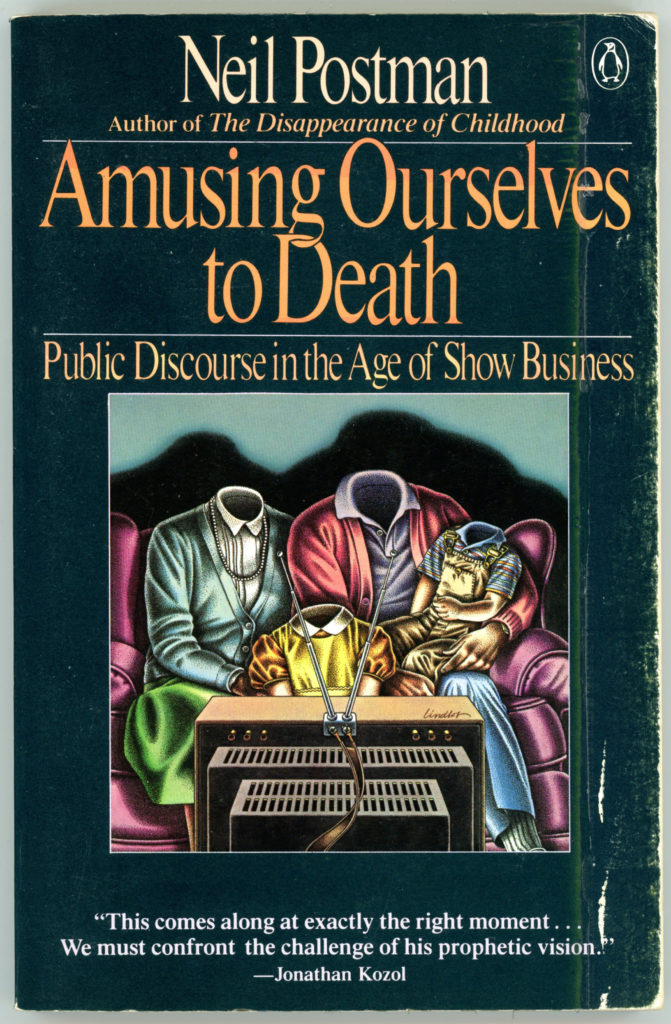

Amusing Ourselves to Death – Public Discourse in The Age of Show Business

by Neil Postman

Penguin Books, 1985 (1986)

____________________

“Ignorance is always correctable. But what shall we do if we take ignorance to be knowledge?”

“But the Founding Fathers did not foresee that tyranny by government might be superseded by another sort of problem altogether, namely, the corporate state…”

“[Huxley] believed that it is far more likely that the Western democracies will dance and dream themselves into oblivion than march into it, single file and manacled. Huxley grasped, as Orwell did not, that it is not necessary to conceal anything from a public insensible to contradiction and narcoticized by technological diversion.”

In both oral and typographic cultures, information derives its importance from the possibilities of action. Of course, in any communication environment, input (what one is informed about) always exceeds output (the possibilities of action based on information). But the situation created by telegraphy, and then exacerbated by later technologies, made the relationship between information and action both abstract and remote. For the first time in human history, people were faced with the problem of information glut, which means that simultaneously they were faced with the problem of a diminished social and political potency. (68)

In both oral and typographic cultures, information derives its importance from the possibilities of action. Of course, in any communication environment, input (what one is informed about) always exceeds output (the possibilities of action based on information). But the situation created by telegraphy, and then exacerbated by later technologies, made the relationship between information and action both abstract and remote. For the first time in human history, people were faced with the problem of information glut, which means that simultaneously they were faced with the problem of a diminished social and political potency. (68)

You may get a sense of what this means by asking yourself another series of questions: What steps do you plan to take to reduce the conflict in the Middle East? Or the rates of inflation, crime and unemployment? What are your plans for preserving the environment or reducing the risk of nuclear war? What do you plan to do about NATO, OPEC, the CIA, affirmative action, and the monstrous treatment of the Baha’is in Iran? I shall take the liberty of answering for you: You plan to do nothing about them. You may, of course, cast a ballot for someone who claims to have some plans, as well as the power to act. But this you can do only once every two or four years by giving one hour of your time, hardly a satisfying means of expressing the broad range of opinions you hold. Voting, we might even say, is the next to last refuge of the politically impotent. The last refuge is, of course, giving your opinion to a pollster, who will get a version of it through a desiccated question, and then will submerge it in a Niagara of similar opinions, and convert them into – what else? – another piece of news. Thus, we have here a great loop of impotence: The news elicits from you a variety of opinions about which you can do nothing except to offer them as more news, about which you can do nothing. (68-69)

Prior to the age of telegraphy, the information-action ratio was sufficiently close so that most people had a sense of being able to control some of the contingencies in their lives. What people knew about had action-value. In the information world created by telegraphy, this sense of potency was lost, precisely because the whole world became the context for news. Everything became everyone’s business. For the first time, we were sent information which answered no question we had asked, and which, in any case, did not permit the right of reply. (69)

We may say then that the contribution of the telegraph to public discourse was to dignify irrelevance and amplify impotence. But this was not all: Telegraphy also made public discourse essentially incoherent. It brought into being a world of broken time and broken attention, to use Lewis Mumford’s phrase. The principal strength of the telegraph was its capacity to move information, not collect it, explain it or analyze it. In this respect, telegraphy was the exact opposite of typography. Books, for example, are an excellent container for the accumulation, quiet scrutiny and organized analysis of information and ideas. It takes time to write a book, and to read one; time to discuss its contents and to make judgments about their merit, including the form of their presentation. A book is an attempt to make thought permanent and to contribute to the great conversation conducted by authors of the past. Therefore, civilized people everywhere consider the burning of a book a vile form of anti-intellectualism. But the telegraph demands that we burn its contents. The value of telegraphy is undermined by applying the tests of permanence, continuity or coherence. The telegraph is suited only to the flashing of messages, each to be quickly replaced by a more up-to-date message. Facts push other facts into and then out of consciousness at speeds that neither permit nor require evaluation. (69-70)

The telegraph introduced a kind of public conversation whose form had startling characteristics: Its language was the language of headlines – sensational, fragmented, impersonal. News took the form of slogans, to be noted with excitement, to be forgotten with dispatch. Its language was also entirely discontinuous. One message had no connection to that which preceded or followed it. Each “headline” stood alone as its own context. The receiver of the news had to provide a meaning if he could. The sender was under no obligation to do so. And because of all this, the world as depicted by the telegraph began to appear unmanageable, even undecipherable. The line-by-line, sequential, continuous form of the printed page slowly began to lose its resonance as a metaphor of how knowledge was to be acquired and how the world was to be understood. “Knowing” the facts took on a new meaning, for it did not imply that one understood implications, background, or connections. Telegraphic discourse permitted no time for historical perspectives and gave no priority to the qualitative. To the telegraph, intelligence meant knowing of lots of things, not knowing about them. (70)

Thus, to the reverent question posed by Morse – What hath God wrought? – a disturbing answer came back: a neighborhood of strangers and pointless quantity; a world of fragments and discontinuities. God, of course, had nothing to do with it. And yet, for all of the power of the telegraph, had it stood alone as a new metaphor for discourse, it is likely that print culture would have withstood its assault; would, at least, have held its ground. As it happened, at almost exactly the same time Morse was reconceiving the meaning of information, Louis Daguerre J was reconceiving the meaning of nature; one might even say, of reality itself. As Daguerre remarked in 1838 in a notice designed to attract investors, “The daguerreotype is not merely an instrument which serves to draw nature … [it] gives her the power to reproduce herself.” (70-71)

Of course both the need and the power to draw nature have always implied reproducing nature, refashioning it to make it comprehensible and manageable. The earliest cave paintings were quite possibly visual projections of a hunt that had not yet taken place, wish fulfillments of an anticipated subjection of nature. Reproducing nature, in other words, is a very old idea. But Daguerre did not have this meaning of “reproduce” in mind. He meant to announce that the photograph would invest everyone with the power to duplicate nature as often and wherever one liked. He meant to say he had invented the world’s first “cloning” device that the photograph was to visual experience what the printing press was to the written word. (71)

In point of fact, the daguerreotype was not quite capable of achieving such an equation. It was not until William Henry Fox Talbot, an English mathematician and linguist, invented the process of preparing a negative from which any number of positives could be made that the mass printing and publication of photographs became possible. The name “photography” was given to this process by the famous astronomer Sir John F.W. Herschel. It is an odd name since it literally means “writing with light.” Perhaps Herschel meant the name to be taken ironically, since it must have been clear from the beginning that photography and writing (in fact, language in any form) do not inhabit the same universe of discourse. (71)

But it is not time constraints alone that produce such fragmented and discontinuous language. When a television show is in process, it is very nearly impermissible to say, “Let me think about that” or “I don’t know” or “What do you mean when you say …?” or “From what sources does your information come?” This type of discourse not only slows down the tempo of the show but creates the impression of uncertainty or lack of finish. It tends to reveal people in the act of thinking, which is as disconcerting and boring on television as it is on a Las Vegas stage. Thinking does not play well on television, a fact that television directors discovered long ago. There is not much to see in it. It is, in a phrase, not a performing art. But television demands a performing art, and so what the ABC network gave us was a picture of men of sophisticated verbal skills and political understanding being brought to heel by a medium that requires them to fashion performances rather than ideas. Which accounts for why the eighty minutes were very entertaining, in the way of a Samuel Beckett play: The intimations of gravity hung heavy, the meaning passeth all understanding. The performances, of course, were highly professional. Sagan abjured the turtle-neck sweater in which he starred when he did “Cosmos.” He even had his hair cut for the event. His part was that of the logical scientist speaking in behalf of the planet. It is to be doubted that Paul Newman could have done better in the role, although Leonard Nimoy might have. Scowcroft was suitably military in his bearing – terse and distant, the unbreakable defender of national security. Kissinger, as always, was superb in the part of the knowing world statesman, weary of the sheer responsibility of keeping disaster at bay. Koppel played to perfection the part of a moderator, pretending, as it were, that he was sorting out ideas while, in fact, he was merely directing the performances. At the end, one could only applaud those performances, which is what a good television program always aims to achieve; that is to say, applause, not reflection.

I do not say categorically that it is impossible to use television as a carrier of coherent language or thought in process. William Buckley’s own program, “Firing Line,” occasionally shows people in the act of thinking but who also happen to have television cameras pointed at them. There are other programs, such as “Meet the Press” or “The Open Mind,” which clearly strive to maintain a sense of intellectual decorum and typographic tradition, but they are scheduled so that they do not compete with programs of great visual interest, since otherwise, they will not be watched. After all, it is not unheard of that a format will occasionally go against the bias of its medium. For example, the most popular radio program of the early 1940’s featured a ventriloquist, and in those days, I heard more than once the feet of a tap dancer on the “Major Bowes’ Amateur Hour.” (Indeed, if I am not mistaken, he even once featured a pantomimist.) (90-91)

Ignorance is always correctable. But what shall we do if we take ignorance to be knowledge? (108)

For all his perspicacity, George Orwell would have been stymied by this situation: there is nothing “Orwellian” about it. The President does not have the press under his thumb. The New York Times and The Washington Post are not Pravda; the Associated Press is not Tass. And there is no Newspeak here. Lies have not been defined as truth nor truth as lies. All that has happened is that the public has adjusted to incoherence and been amused into indifference. Which is why Aldous Huxley would not in the least be surprised by the story. Indeed, he prophesied its coming. He believed that it is far more likely that the Western democracies will dance and dream themselves into oblivion than march into it, single file and manacled. Huxley grasped, as Orwell did not, that it is not necessary to conceal anything from a public insensible to contradiction and narcoticized by technological diversion. Although Huxley did not specify that television would be our main line to the drug, he would have no difficulty accepting Robert MacNeil’s observation that “Television is the soma of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World.” Big Brother turns out to be Howdy Doody. (110-111)

As Xenophanes remarked twenty-five centuries ago, men always make their gods in their own image. But to this, television politics had added a new wrinkle: Those who would be gods refashion themselves into images the viewers would have them be.

It follows from this that history can play no significant role in image politics. For history is of value only to someone who takes seriously the notion that there are patterns in the past which may provide the present with nourishing traditions. “The past is a world,” Thomas Carlyle said, “and not a void of grey haze.” But he wrote this at a time when the book was the principal medium of serious public discourse. A book is all history. Everything about it takes one back in time – from the way it is produced to its linear mode of exposition to the fact that the past tense is its most comfortable form of address. As no other medium before or since, the book promotes a sense of a coherent and usable past. In a conversation of books, history, as Carlyle understood it, is not only a world but a living world. It is the present that is shadowy.

But television is a speed-of-light medium, a present-centered medium. Its grammar, so to say, permits no access to the past. Everything presented in moving pictures is experienced as happening “now,” which is why we must be told in language that a videotape we are seeing was made months before. Moreover, like its forefather, the telegraph, television needs to move fragments of information, not to collect and organize them. Carlyle was more prophetic than he could imagine: The literal gray haze that is the background void on all television screens is an apt metaphor of the notion of history the medium puts forward. In the Age of Show Business and image politics, political discourse is emptied not only of ideological content but of historical content, as well.

Czeslaw Milosz, winner of the 1980 Nobel Prize for Literature, remarked in his acceptance speech in Stockholm that our age is characterized by a “refusal to remember”; he cited, among other things, the shattering fact that there are now more than one hundred books in print that deny that the Holocaust ever took place. The historian Carl Schorske has, in my opinion, circled closer to the truth by noting that the modern mind has grown indifferent to history because history has become useless to it; in other words, it is not obstinacy or ignorance but a sense of irrelevance that leads to the diminution of history. Television’s Bill Moyers inches still closer when he says, “I worry that my own business … helps to make this an anxious age of agitated amnesiacs. … We Americans seem to know everything about the last twenty-four hours but very little of the last sixty centuries or the last sixty years.” Terence Moran, I believe, lands on the target in saying that with media whose structure is biased toward furnishing images and fragments, we are deprived of access to an historical perspective. In the absence of continuity and context, he says, “bits of information cannot be integrated into an intelligent and consistent whole.” We do not refuse to remember; neither do we find it exactly useless to remember. Rather, we are being rendered unfit to remember. For if remembering is to be something more than nostalgia, it requires a contextual basis – a theory, a vision, a metaphor – something within which facts can be organized and patterns discerned. The politics of image and instantaneous news provides no such context, is, in fact, hampered by attempts to provide any. A mirror records only what you are wearing today. It is silent about yesterday. With television, we vault ourselves into a continuous, incoherent present. “History,” Henry Ford said, “is bunk.” Henry Ford was a typographic optimist. “History,” the Electric Plug replies, “doesn’t exist.”

If these conjectures make sense, then in this Orwell was wrong once again, at least for the Western democracies. He envisioned the demolition of history, but believed that it would be accomplished by the state; that some equivalent of the Ministry of Truth would systematically banish inconvenient facts and destroy the records of the past. Certainly, this is the way of the Soviet Union, our modern-day Oceania. But as Huxley more accurately foretold it, nothing so crude as all that is required. Seemingly benign technologies devoted to providing the populace with a politics of image, instancy and therapy may disappear history just as effectively, perhaps more permanently, and without objection.

We ought also to look to Huxley, not Orwell, to understand the threat that television and other forms of imagery pose to the foundation of liberal democracy – namely, to freedom of information. Orwell quite reasonably supposed that the state, through naked suppression, would control the flow of information, particularly by the banning of books. In this prophecy, Orwell had history strongly on his side. For books have always been subjected to censorship in varying degrees wherever they have been an important part of the communication landscape. In ancient China, the Analects of Confucius were ordered destroyed by Emperor Chi Huang Ti. Ovid’s banishment from Rome by Augustus was in part a result of his having written Ars Amatoria. Even in Athens, which set enduring standards of intellectual excellence, books were viewed with alarm. In Areopagitica, Milton provides an excellent review of the many examples of book censorship in Classical Greece, including the case of Protagoras, whose books were burned because he began one of his discourses with the confession that he did not know whether or not there were gods. But Milton is careful to observe that in all the cases before his own time, there were only two types of books that, as he puts it, “the magistrate cared to take notice of”: books that were blasphemous and books that were libelous. Milton stresses this point because, writing almost two hundred years after Gutenberg, he knew that the magistrates of his own era, if unopposed, would disallow books of every conceivable subject matter. Milton knew, in other words, that it was in the printing press that censorship had found its true metier; that, in fact, information and ideas did not become a profound cultural problem until the maturing of the Age of Print. Whatever dangers there may be in a word that is written, such a word is a hundred times more dangerous when stamped by a press. And the problem posed by typography was recognized early; for example, by Henry VIII, whose Star Chamber was authorized to deal with wayward books. It continued to be recognized by Elizabeth I, the Stuarts, and many other post-Gutenberg monarchs, including Pope Paul IV, in whose reign the first Index Librorum Prohibitorum was drawn. To paraphrase David Riesman only slightly, in a world of printing, information is the gunpowder of the mind; hence come the censors in their austere robes to dampen the explosion.

Thus, Orwell envisioned that (1) government control over (2) printed matter posed a serious threat for Western democracies. He was wrong on both counts. (He was, of course, right on both counts insofar as Russia, China and other pre-electronic cultures are concerned.) Orwell was, in effect, addressing himself to a problem of the Age of Print – in fact, to the same problem addressed by the men who wrote the United States Constitution. The Constitution was composed at a time when most free men had access to their communities through a leaflet, a newspaper or the spoken word. They were quite well positioned to share their political ideas with each other in forms and contexts over which they had competent control. Therefore, their greatest worry was the possibility of government tyranny. The Bill of Rights is largely a prescription for preventing government from restricting the flow of information and ideas. But the Founding Fathers did not foresee that tyranny by government might be superseded by another sort of problem altogether, namely, the corporate state, which through television now controls the flow of public discourse in America. (135-139)

What Huxley teaches is that in the age of advanced technology, spiritual devastation is more likely to come from an enemy with a smiling face than from one whose countenance exudes suspicion and hate. In the Huxleyan prophecy, Big Brother does not watch us, by his choice. We watch him, by ours. There is no need for wardens or gates or Ministries of Truth. When a population becomes distracted by trivia, when cultural life is redefined as a perpetual round of entertainments, when serious public conversation becomes a form of baby-talk, when, in short, people become an audience and their public business a vaudeville act, then a nation finds itself at risk; culture-death is a clear possibility. (155-156)

To be unaware that a technology comes equipped with a program for social change, to maintain that technology is neutral, to make the assumption that technology is always a friend to culture is, at this late hour, stupidity plain and simple. Moreover, we have seen enough by now to know that technological changes in our modes of communication are even more ideology-laden than changes in our modes of transportation. Introduce the alphabet to a culture and you change its cognitive habits, its social relations, its notions of community, history and religion. Introduce the printing press with moveable types, and you do the same. Introduce speed-of-light transmission of images and you make a cultural revolution. Without a vote. Without polemics. Without guerilla resistance. Here is ideology, pure if not serene. Here is ideology without words, and all the more powerful for their absence. All that is required to make it stick is a population that devoutly believes in the inevitability of progress. And in this sense, all Americans are Marxists, for we believe nothing if not that history is moving us toward some preordained paradise and that technology is the force behind that movement. (157-158)

It is an irony that I have confronted many times in being told that I must appear on television to promote a book that warns people against television. Such are the contradictions of a television-based culture. (159)