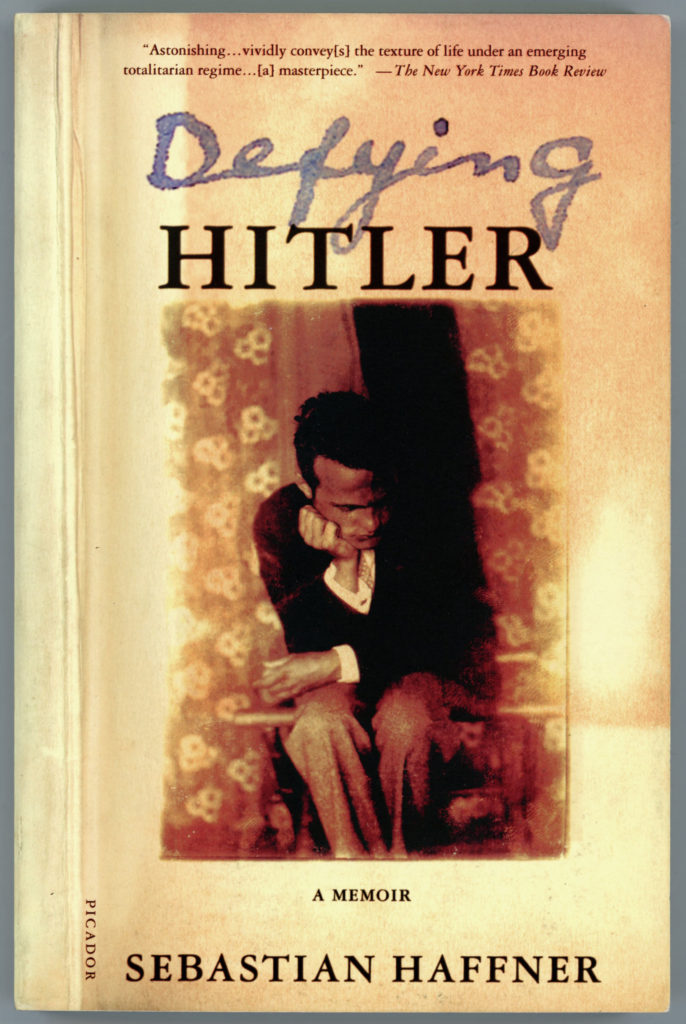

Defying Hitler – A Memoir

by Sebastian Haffner (Raimund Pretzel)

Picador (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) – 2000 (2002)

(First published in Germany by Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt as

Geschichte eines Deutschen: Die Erinnerungen 1914-1933)

__________

Is it not said that in peacetime the chiefs of staff always prepare their armies as well as possible – for the previous war? I cannot judge that truth of that, but it is certainly true that conscientious parents always educate their sons for the era that is just over. I had all the intellectual endowments to play a decent part in the bourgeois world of the period before 1914. I had an uneasy feeling, based on what I had experienced, that it would not be much help to me. That was all. At best I smelled a warning whiff of what was about to confront me, but I did not have an intellectual system that would help me deal with it.

Defying Hitler is an account of the political, economic, social, and cultural changes that Sebastian Haffner (pen name of Raimund Pretzel) observed and experienced from the 1920s through the 1930s, during Germany’s descent into a totalitarian dictatorship. Superbly written, the book proceeds in a generally chronological fashion, counterposing observation and analysis of events in German society as a whole, against moving, detailed, emotionally intimate anecdotes concerning the live of Haffner’s family members, friends, and social acquaintances. A particular strength of the book is the style of Haffner’s writing, which delivers accounts of events in the (then) “here and now” through an urgent, morally impassioned, almost novelistic tone. If a single word can be used – albeit inadequately – to characterize Haffner’s message, that word would be “wisdom”, for his thoughts about human nature, whether that nature be individual or collective, are applicable to all eras and societies.

Defying Hitler is an account of the political, economic, social, and cultural changes that Sebastian Haffner (pen name of Raimund Pretzel) observed and experienced from the 1920s through the 1930s, during Germany’s descent into a totalitarian dictatorship. Superbly written, the book proceeds in a generally chronological fashion, counterposing observation and analysis of events in German society as a whole, against moving, detailed, emotionally intimate anecdotes concerning the live of Haffner’s family members, friends, and social acquaintances. A particular strength of the book is the style of Haffner’s writing, which delivers accounts of events in the (then) “here and now” through an urgent, morally impassioned, almost novelistic tone. If a single word can be used – albeit inadequately – to characterize Haffner’s message, that word would be “wisdom”, for his thoughts about human nature, whether that nature be individual or collective, are applicable to all eras and societies.

Published in 2002, the book was the focus of discussion at the chicagoboyz blog (and subsequently at neoneocon), where David Foster’s two blog posts generated a variety of substantive and insightful responses.

Presented below are a variety of passages from Defying Hitler, which give only a small inkling of the book’s power and message, which are difficult to overstate.

____________________

A childish illusion, fixed in the minds of all children born in a certain decade and hammered home for four years, can easily reappear as a deadly serious political ideology twenty years later.

__________

The young and quick-witted did well. Overnight they became fine, rich, and independent. It was a situation in which mental inertia and reliance on past experience were punished by starvation and death, but rapid appraisal of new situations and speed of reaction were rewarded with sudden, vast riches.

__________

It took me quite a while to realize that my youthful excitability was right and my father’s wealth of experience was wrong; that there are things that cannot be dealt with by calm skepticism.

__________

It is a commonly held belief that caution is just as dangerous as recklessness, and that caution deprives one of the pleasure of taking risks. Incidentally, everything I have experienced in my life reinforces the truth of this perception.

____________________

…in its reactions the mass psyche greatly resembles the child psyche. Our cannot overstate the childishness of the ideas that feed and stir the masses. Real ideas must as a rule be simplified to the level of a child’s understanding if they are to arouse the masses to historic actions. A childish illusion, fixed in the minds of all children born in a certain decade and hammered home for four years, can easily reappear as a deadly serious political ideology twenty years later.

From 1914 to 1918 a generation of German schoolboys daily experienced war as a great, thrilling, enthralling game between nations, which provided far more excitement and emotional satisfaction than anything peace could offer; and that has now become the underlying vision of Nazism. That is where it draws its allure from: its simplicity, its appeal to the imagination, and its zest for action; but also its intolerance and its cruelty towards internal opponents. Anyone who does not join in the game is regarded not as an adversary but as a spoilsport. Ultimately that is also the source of Nazism’s belligerent attitude towards neighboring states. Other countries are not regarded as neighbors, but must be opponents, whether they like it or not. Otherwise the march would have to be called off!

Many things later bolstered Nazism and modified its character, but its roots lie here: in the experience of war – not by German soldiers at the front, but by German schoolboys at home. Indeed, the front-line generation produced relatively few genuine Nazis and is better known for its “critics and carpers.” (16-17)

_____________________

It is interesting to note that, in the spring of 1919, when the revolution of the left tried in vain to establish itself, the Nazi revolution was already fully formed and potent. It lacked only Hitler. (34)

______________________

…Soon after the beginning of the Ruhr War, the dollar shot to twenty thousand marks, rested there for a time, jumped to forty thousand, paused again, and then, with small periodic fluctuations, coursed through the ten thousands and then the hundred thousands. No one quite knew how it happened. Rubbing our eyes, we followed its progress like some astonishing natural phenomenon. It became the topic of the day. Then suddenly, looking around, we discovered that this phenomenon had devastated the fabric of our daily lives.

Anyone who had savings in a bank or bonds saw their value disappear overnight. Soon it did not matter whether it was a penny put away for a rainy day or a vast fortune. Everything was obliterated. Many people quickly moved their investments only to find that it made no difference. Very soon it became clear that something had happened that forced everyone to forget about their savings and attend to a far more urgent matter.

The cost of living had begun to spiral out of control. Traders followed hard on the heels of the dollar. A pound of potatoes which yesterday had cost fifty thousand marks now cost a hundred thousand. The salary of sixty-five thousand marks brought home the previous Friday was no longer sufficient to buy a pack of cigarettes on Tuesday.

***

The old and unworldly had the worst of it. Many were driven to begging; many to suicide. The young and quick-witted did well. Overnight they became fine, rich, and independent. It was a situation in which mental inertia and reliance on past experience were punished by starvation and death, but rapid appraisal of new situations and speed of reaction were rewarded with sudden, vast riches. The twenty-one year old bank director appeared on the scene, and also the high school senior who earned his living from the stock-market tips of his slightly older friends. He wore Oscar Wilde ties, organized champagne parties, and supported his embarrassed father. (55-56)

______________________

We had the great war game behind us and the shock of defeat, the disillusionment of the revolution that had followed, and now the daily spectacle of the failure of all the rules of life, and the bankruptcy of age and experience. We had lived through a series of contradictory creeds: pacifism, nationalism, and then Marxism. (This last has much in common with sexual infatuation: both are unofficial, slightly illicit, both use shock tactics, both mistake an important though officially taboo part for the whole, sex in the one case and economics in the other.) (61)

______________________

Now something strange happened – and with this I believe I am about to reveal one of the most fundamental political events of our time, something that was not reported in any newspaper: by and large that invitation was declined. It was not what was wanted. A whole generation was, it seemed, at a loss as to how to cope with the offer of an unfettered private life.

A generation of young Germans had become accustomed to having the entire content of their lives delivered gratis, so to speak, by the public sphere, all the raw material for their deeper emotions, for love and hate, joy and sorrow, but also all their sensations and thrills – accompanied though they might be by poverty, hunger, death, chaos and peril. Now that these deliveries suddenly ceased, people were left helpless, impoverished, robbed, and disappointed. They had never learned to live from within themselves, how to make an ordinary private life great, beautiful, and worthwhile, how to enjoy it and make it interesting. So they regarded the end of the political tension and the return of private liberty not as a gift, but as a deprivation. They were bored, their minds strayed to silly thoughts, and they began to sulk. In the end they waited eagerly for the first disturbance, and first setback or incident, so that they could put this period of peace behind them and set out on some new collective adventure. (68-69)

______________________

…the younger generation had grown up without fixed customs and traditions.

Outside this cultured class, the great danger of life in Germany has always been emptiness and boredom (with the exception perhaps of certain geographical border regions such as Bavaria and the Rhineland, where a whiff of the south, some romance, and a sense of humor enter the picture.) The menace of monotony hangs, as it has always hung, over the great plains of northern and eastern Germany, with their colorless towns and their all too industrious, efficient, and conscientious businesses and organizations. With it comes a horror vacui and the yearning for ‘salvation’: through alcohol, through superstition, or, best of all, through a vast, overpowering, cheap mas intoxication.

The basic fact that in Germany only a minority (not necessarily from the aristocracy or the moneyed class) understands anything of life and knows how to lead it – a fact that, incidentally, makes the country inherently unsuitable for democratic governments – had been dangerously exacerbated by the events of the years from 1914 to 1924. The older generation had become uncertain and timid in its ideals and convictions and began to focus on “youth,” with thoughts of abdication, flattery, and high expectations. Young people themselves were familiar with nothing but political clamor, sensation, anarchy, and the dangerous lure of irresponsible numbers games. They were only waiting to put that they had witnessed into practice themselves, but on a far larger scale. Meanwhile, they viewed private life as “boring,” “bourgeois,” and “old-fashioned.” The masses, too, were accustomed to all the varied sensations of disorder. Moreover, they had become weak and doubtful about their most recent great superstition: the creed, celebrated with pedantic, orthodox fervor, of the magical powers of the omniscient Saint Marx and the inevitability of the automatic course of history prophesized by him. (70-71)

______________________

Many of those who began to acclaim Hitler at the Sportpalast in 1930 would probably have avoided asking him for a light if they had met him in the street. That was the strange thing: their fascination with the boggy, dripping cesspool he represented, repulsiveness taken to extremes. No one would have been surprised if a policeman had taken him by the scruff of the neck in the middle of his first speech and removed him to some place from which he would never have emerged again, and where he doubtless belonged. As nothing of the sort happened and, on the contrary, the man surpassed himself, becoming ever more deranged and monstrous, and also ever more notorious, more impossible to ignore, the effect was reversed. It was then that the real mystery of the Hitler phenomenon began to show itself: the strange befuddlement and numbness of his opponents, who could not cope with his behavior and found themselves transfixed by the gaze of the basilisk, unable to see that it was hell personified that challenged them. (88-89)

______________________

…I can only smile ruefully when I consider how prepared I was for the adventure that awaited me. I was not prepared at all. I had no skills in boxing or jujitsu, not to mention smuggling, crossing borders illegally, using secret codes, and so on; skills that would have stood me in good stead in the coming years. My spiritual preparation for what was ahead was almost equally inadequate. Is it not said that in peacetime the chiefs of staff always prepare their armies as well as possible – for the previous war? I cannot judge that truth of that, but it is certainly true that conscientious parents always educate their sons for the era that is just over. I had all the intellectual endowments to play a decent part in the bourgeois world of the period before 1914. I had an uneasy feeling, based on what I had experienced, that it would not be much help to me. That was all. At best I smelled a warning whiff of what was about to confront me, but I did not have an intellectual system that would help me deal with it. (102)

______________________

…In each individual case the process of becoming a Nazi showed the unmistakable symptoms of nervous collapse.

The simplest and, if you looked deeper, nearly always the most basic reason was fear. Join the thugs to avoid being beaten up. Less clear was a kind of exhilaration, the intoxication of unity, the magnetism of the masses. Many also felt a need for revenge against those who had abandoned them. Then there was a peculiarly German line of thought: “All the predictions of the opponents of the Nazis have not come true. They said the Nazis would not win. Now they have won. Therefore the opponents were wrong. So the Nazis must be right.” There was also (particularly among intellectuals) the belief that they could change the face of the Nazi Party by becoming a member, even now shift its direction. Then, of course, many just jumped on the bandwagon, wanting to be a part of a perceived success. Finally, among the more primitive, inarticulate, simpler souls there was a process that might have taken place in mythical times when a beaten tribe abandoned its faithless god and accepted the god of the victorious tribe as its patron. Saint Marx, in whom one had always believed, had not helped. Saint Hitler was obviously more powerful. So let’s destroy the images of Saint Marx on the altars and replace them with images of Saint Hitler. Let us learn to pray: “It is the Jews’ fault” rather than “It is the capitalists’ fault.” Perhaps that will redeem us. (134-135)

______________________

In spite of all our historical and cultural education, how completely helpless we were to deal with something that just did not feature in anything we had learned! (136)

______________________

Yes, roared and raged during that March of 1933. Yes, I frightened my parents with wild proposals: I would leave the law courts; I would emigrate and demonstratively convert to Judaism. But it went no further than the expression of these intentions. Though it was not really relevant to current events, my father’s immense experience of the period from 1870 to 1933 was deployed to calm me down and sober me up. He treated my heated emotions with gentle irony. I must admit that calm skepticism has always had a stronger influence on me than emotionally proclaimed conviction. It took me quite a while to realize that my youthful excitability was right and my father’s wealth of experience was wrong; that there are things that cannot be dealt with by calm skepticism. I lacked the self-confidence to draw active conclusions from my feelings. (138)

______________________

Apart from the terror, the unsettling and depressing aspect of the first murderous declaration of intent was that it triggered a flood of arguments and discussions all over Germany, not about anti-Semitism but about the “Jewish question”. This is a trick the Nazis have since successfully repeated many times on other “questions” and in international affairs. By publicly threatening a person, an ethnic group, a nation, or a region with death and destruction, they provoke a general discussion not about their own existence, but about the right of their victims to exist. In this way that right is put in question. (142)

______________________

What is history, and where does it take place?

If you read ordinary history books – which, it is often overlooked, contain only the scheme of events, not the events themselves – you get the impression that no more than a few dozen people are involved, who happen to be “at the helm of the ship of state” and whose deeds and decisions form what is called history. According to this view, the history of the present decade is a kind of chess game among Hitler, Mussolini, Chiang Kai-shek, Roosevelt, Chamberlain, Daladier, and a number of other men whose names are on everybody’s lips. We anonymous others seem at best to be the objects of history, pawns in the chess game, who may be pushed forward or left standing, sacrificed or captured, but whose lives, for what they are worth, take place in a totally different world, unrelated to what is happening on the chessboard, of which they are quite unaware.

It may seem a paradox, but it is nonetheless the simple truth, to say that on the contrary, the decisive historical events take place among us, the anonymous masses. The most powerful dictators, ministers, and generals are powerless against the simultaneous mass decisions taken individually and almost unconsciously by the population at large. It is characteristic of these decisions that they do not manifest themselves as mass movements or demonstrations. Mass assemblies are quite incapable of independent action. Decisions that influence the course of history arise out of the individual experiences of thousands of millions of individuals. (182-183)

______________________

There is an unsolved riddle in the creation of the Third Reich. I think it is much more interesting than the question of who set fire to the Reichstag. It is the question “What became of the Germans?” Even on March 5, 1933, a majority of them voted against Hitler. What happened to that majority? Did they die? Did they disappear from the face of the earth? Did they become Nazis at this late stage? How was it possible that there was not the slightest visible reaction from them?

Most of my readers will have met one or more Germans in the past, and most of them will have looked on their German acquaintances as normal, friendly, civilized people like anyone else – apart from the usual idiosyncrasies. When they hear the speeches coming from Germany today (and become aware of the foulness of the deeds emanating from them), most of these people will think of their acquaintances and be aghast. They will ask, “What’s wrong with them? Don’t they see what’s happening to them – and what is happening in their name? Do they approve of it? What kind of people are they? What are we to think of them?”

Indeed, behind these questions there are some very peculiar, very revealing mental processes and experiences, whose historical significance cannot yet be fully gauged. These are what I want to write about. You cannot come to grips with them if you do not track them down to the place where they happen: the private lives, emotions, and thoughts of individual Germans. They happen there all the more since, having cleaned the sphere of politics of all opposition, the conquering, ravenous state has moved into formerly private spaces in order to clear these, too, of any resistance or recalcitrance and to subjugate the individual. There, in private, the fight is taking place in Germany. You will search for it in vain in the political landscape, even with the most powerful telescope. Today the political struggle is expressed by the choice of what a person eats and drinks, whom he loves, what he does in his spare time, whose company he seeks, whether he smiles or frowns, what he reads, what pictures he hangs on his walls. It is here that the battles of the next world are being decided in advance. That may sound grotesque, but it is the truth. (181-185)

______________________

The plight of non-Nazi Germans in the summer of 1933 was certainly one of the most difficult a person can find himself in: a condition in which one is hopelessly, utterly overwhelmed, accompanied by the shock of having been caught completely off balance. We were in the Nazis’ hands for good or ill. All lines of defense had fallen, any collective resistance had become impossible. Individual resistance was only a form of suicide. We were pursued into the furthest corners of our private lines; in all areas of life there was rout, panic, and flight. No one could tell where it would end. At the same time we were called upon, not to surrender, but to renege. Just a little pact with the devil – and you were no longer one of the captured quarry. Instead you were one of the victorious hunters. (199-200)

______________________

My attempt to seclude myself in a small, secure, private domain failed very quickly. The reason was that there was no such domain. Very soon the wind whistled into my private life from all sides and blew it apart. By the autumn there was nothing left of what I had considered my “circle of friends”.

For instance, there was a small “working group” of six young intellectuals, all of them Referendars approaching the Assessor examinations, all from the same social class. I was one of them. We prepared for the exams together, and that was the outward reason the group had been formed. But it had long since become something more than that and formed a small, intimate debating club. We had very different political opinions, but would not have dreamed of hating one another for them. Indeed, we were all on very good terms. The opinions were not diametrically opposed, rather – in a manner typical of the range of views held by young intellectual Germans in 1932 – they formed a circle. The extreme ends of the arc almost met.

The most “left-wing” member was Hessel, a doctor’s son with Communist sympathies; the most “right-wing” was Holz, an officer’s son who held military, nationalistic views. Yet they often made a common front against the rest of us. They both came from the “youth movement” and both thought in terms of leagues. They were both anti-bourgeois and anti-individualistic. Both had an ideal of “community” and “community spirit”. For both, jazz music, fashion magazines, the Kurfurstendamm*, in other words the world of glamour and “easy come, easy go,” were a red rag. Both had a secret liking for terror, in a more humanistic garb for the one, more nationalistic for the other. As similar views make for similar faces, they both had a certain stiff, thin-lipped, humorless expression and, incidentally, the greatest respect for each other. Courtesy was anyway a matter of course among the members of the group.

*In prewar Berlin the city center was where Freidrichstrasse and Unter der Linden intersected. The Kurfurstendamm to the west was an area of nightlife. (208-209)

______________________

No, retiring into private life was not an option. However far one retreated, everywhere one was confronted with the very thing one had been fleeing from. I discovered that the Nazi revolution had abolished the old distinction between politics and private life, and that it was quite impossible to treat it merely as a “political event”. It took place not only in the sphere of politics, but also in each individual private life; it seeped through the walls like poison gas. If you wanted to evade the gas there was only one option: to remove yourself physically – emigration. Emigration: that meant saying goodbye to the country of one’s birth, language, and education and severing all patriotic ties. (219)

The first country to be occupied by the Nazis was not Austria or Czechoslovakia. It was Germany. (225)

It is a commonly held belief that caution is just as dangerous as recklessness, and that caution deprives one of the pleasure of taking risks. Incidentally, everything I have experienced in my life reinforces the truth of this perception. (229)