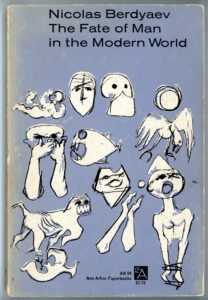

Nicolas Berdyaev

(Никола́й Алекса́ндрович Бердя́ев)

The Fate of Man in the Modern World

(Судьба Человечества в Современном Мире)

The University of Michigan Press

(1934, 1935) 1955, 1961

Translated by Donald A. Lowrie

Economics, which should have aided man, instead of being for his service, is discovered to be that for which man exists: the non-human economic process.

The autonomy of economic life, for instance, created the fatal figure of the “economic man” who is really no man at all.

Even our epoch, so proud of its science and its technical achievements is steeped in myth: science and technics have themselves become myths.

History has always worked for the general or universal, rather than for the private or individual. (9)

History has always worked for the general or universal, rather than for the private or individual. (9)

We shall see that in all the present historical process(es) a greater role than that or the war is played by another force, a force of far longer duration, a force or almost cosmic significance: technics* and the mechanization of life. (14)

Economics, which should have aided man, instead of being for his service, is discovered to be that for which man exists: the non-human economic process. (16)

But it is noteworthy that at a time when every religious sanction of authority has vanished, we live in a very authoritarian epoch. (17) The urge toward an authoritarian form of life is felt throughout the whole world: the liberal element seems completely discredited. But the sanctions for authority are now different from what they once were. Authority is born of new collectives, and these collectives clothe their new leaders with authority more absolute than was that of the former anointed monarchs. (17-18)

Technical civilization demands that man shall fulfill one or another of his functions, but it does not want to reckon with man himself – it knows only his functions. This is not dissolving man in nature, but making him into a machine. (33)

The emancipation did not set free the whole man, it simply liberated thought itself, as a sphere quite apart from human existence; it was the declaration of autonomy for thought, not for man himself. This autonomy was proclaimed in all spheres of social and cultural life, and everywhere it brought about the dissociation of these various phases of life from the integral man. The autonomy of economic life, for instance, created the fatal figure of the “economic man” who is really no man at all. (57)

…absolute monism, absolute ideocracy, is realizable without any real unity of belief. Such a thing as unity of belief does not exist in a single society or state to-day. An obligatory unity is obtained by a sort of collective emotional demonic possession. Unity is attained by the dictatorship of a party which makes itself the equivalent of the state. From the sociological viewpoint it is very interesting that freedom is constantly diminishing in the world, not only in comparison with societies founded on liberal and democratic principles, but even in comparison with the old monarchical and aristocratic societies where, actually, there was more liberty, in spite of the fact that there was far greater unity in the matter of religious faith. In the older social forms, really great liberty was assured for fairly limited groups – liberty was an aristocratic privilege. When the circle was widened and society made uniform, instead of freedom being extended to all, it is non-freedom which becomes universal: all are equally subject to the state or to society. A socially differentiated order preserved certain liberties for an elect group. Freedom is an aristocratic rather than a democratic privilege. Tocqueville saw in democracy a danger for liberty. The same problem is posed by Marx and Mussolini as illustrated in Communism and Fascism. (69)

…the process now at work in the world means not only the end of individualism, but also terrible danger to the eternal truth of personalism, which means a threat to the very existence of human personality. In the collective, personal consciousness is extinguished and replaced by that of the collective itself. Thought is regimented, and instead of personal conscience we have the conscience of the group. The change in consciousness is so radical that even the attitudes toward truth and falsehood are changed. What once was falsehood to the personal consciousness now becomes part of human duty in the conscience of the collective. Thinking, as well as critical judgement, is compelled to march in step. (74)

Modern collectives are not organic but mechanical. The modern man can be organized only technically and the power of technics is in keeping with our democratic era. Technics rationalize human life, but this rationalization has irrational results, such as unemployment which seems ever more closely to be the future in store for man. The social question is made a matter above all of distribution, that is not merely an economic, but a moral question. The present state of the world calls for a moral and spiritual revolution, revolution in the name of personality, of man, of every single person. This revolution should restore the hierarchy of values, now quite shattered, and place the value of human personality above the idols of production, technics, the state, the race or nationality, the collective. (82-83)

Even our epoch, so proud of its science and its technical achievements is steeped in myth: science and technics have themselves become myths. (95)

…it is surprising to note how authority in our modern world, based upon the subconscious and irrational, adopts the methods of extreme rationalism, the technicalization of human life: it proclaims rationalized state planning, not only for economics, but for human thought and conscience, even for personal sexual and erotic life. Modern rationalization and technicalization are controlled by subconscious and irrational instincts, the instincts of violence and domination. (105-106)

Bread for myself is a material question: bread for my neighbor is a spiritual question. (124)

*This word, increasingly used in several other languages, stands for the sum of modern scientific progress, especially technical and mechanical: it is the modern “civilization,” which some continental people like to contrast with their own “culture.” – David A. Lowrie