Books leave impressions. Maybe this is by virtue of a book’s very subject matter; perhaps it’s because of an author’s literary style; possibly this arises from a book’s symbolism and message. And maybe, just maybe, it’s a matter of “age”: That is, the chance intersection between the era symbolized by a book’s year of publication, and, your “own” age as a reader of that book.

I think this was so for me when I first read Quentin Reynold’s 70,000 to 1 in the late 1960s. Among the many books in my father’s library (the number seemed innumerable to me at the time, though in retrospect it was hardly so!), more than once I carried 70,000 to 1, Gene Gurney’s Five Down and Glory, or, William Green’s Famous Fighters of the Second World War (specifically, volume I of Famous Fighters; I discovered Volume II some years later) – to elementary school, where – whenever free time permitted, I immersed myself with curiosity, wonder and not-a-little-awe, within a past that that only recently – just a little over two decades previously – had passed. After all – so yes, this “dates” me – this was in the late 1960s, only two and a half decades after the end of the Second World War.

As so, in 70,000 to I, I read with wonder about the experiences of Sergeant Gordon Manuel of the B-17 Flying Fortress Honi Kuu Okole, incorrectly noted in the book – as I discovered later! – as Kai O Keleiwa. As you can appreciate from Justin Taylan’s book review of 70,000 to 1 at Pacific Wrecks, author Quentin Reynolds combines themes of military aviation, escape and evasion, and wilderness survival, to create a contemporary, fast-paced version of Robinson Crusoe.

A particularly inspiring aspect of the book was Reynold’s account of how Manuel met, and was eventually rescued with, American fighter pilots Owen Giertsen, Edward Czarnecki and Carl Planck. Those names must have left an impression upon me: In 2014, as I reviewed the photos in Photographic Prints of Air Cadets and Officers, Air Crew, and Notables in the History of Aviation – NARA RG 18-PU, I was more than intrigued to discover Czarnecki’s and Planck’s portraits: “So, that’s who they were!”

Their pictures appear below.

______________________________________

But, first (!) here’s the cover of the first (1946) hardback edition of 70,000 to 1, which features art by Miriam Woods. (You can view this and other aeronautically themed book art, and many other examples of cover art from books and pulp-fiction magazines, at my brother blog, WordsEnvisioned. (* Shameless plug *)

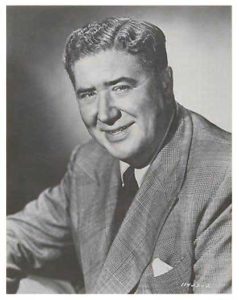

Here’s Quentin Reynolds. Specifically, Quentin James Reynolds.

Quentin James Reynods, at Wikipedia

Quentin James Reynolds, at FindAGrave

Gordon R. Manuel, at Pacific Wrecks

_______________________________________

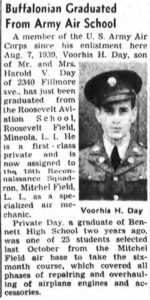

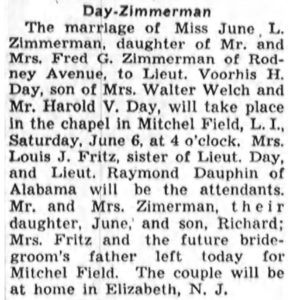

Second Lieutenant Edward John Czarnecki

431st Fighter Squadron, 475th Fighter Group, 5th Air Force

Edward J. Czarnekci, at Pacific Wrecks

P-38H 42-66948, at Pacific Wrecks

Edward J. Czarnecki, at FindAGrave

Here’s an official WW II Army Air Force Photograph of Lt. Czarnecki and two other fighter pilots, undated image 59978AC (A48682). Caption: “This trio of P-38 Lightning pilots knocked down five Japanese Zeros in engagements near Wewak, New Guinea on August 16 and 18, 1943, when more than 200 enemy planes were destroyed. They are, left to right: Capt. William Walderman of Santa Monica, Calif.; 2nd Lt. Edward Czarnecki of Wilmington, Del.; and 1st Lt. Jack Mankin of Kansas City, Mo. Their count: Walderman, one; and two each for Czarnecki and Mankin.”

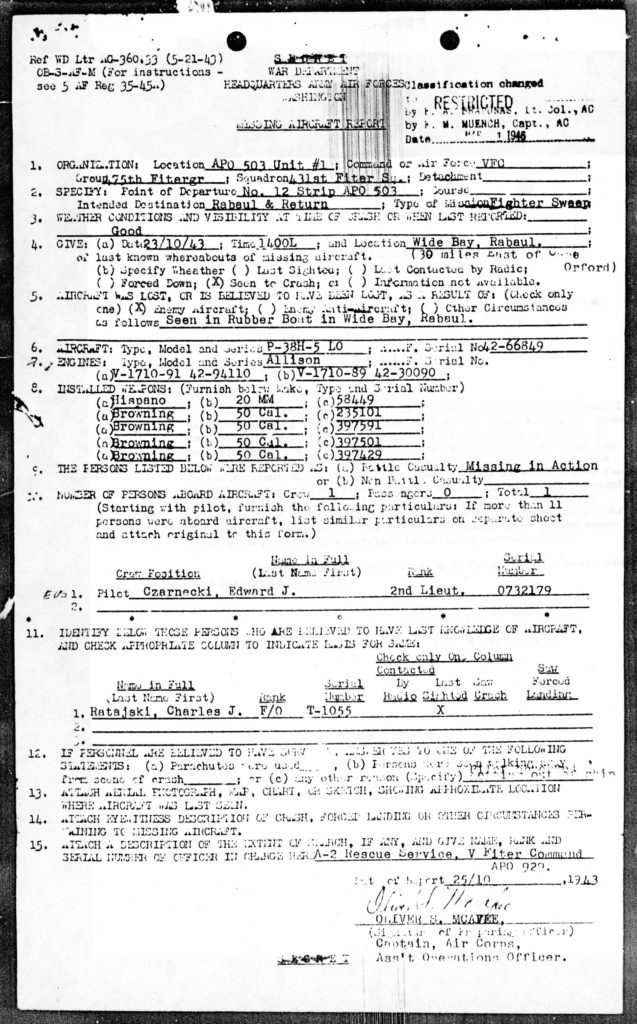

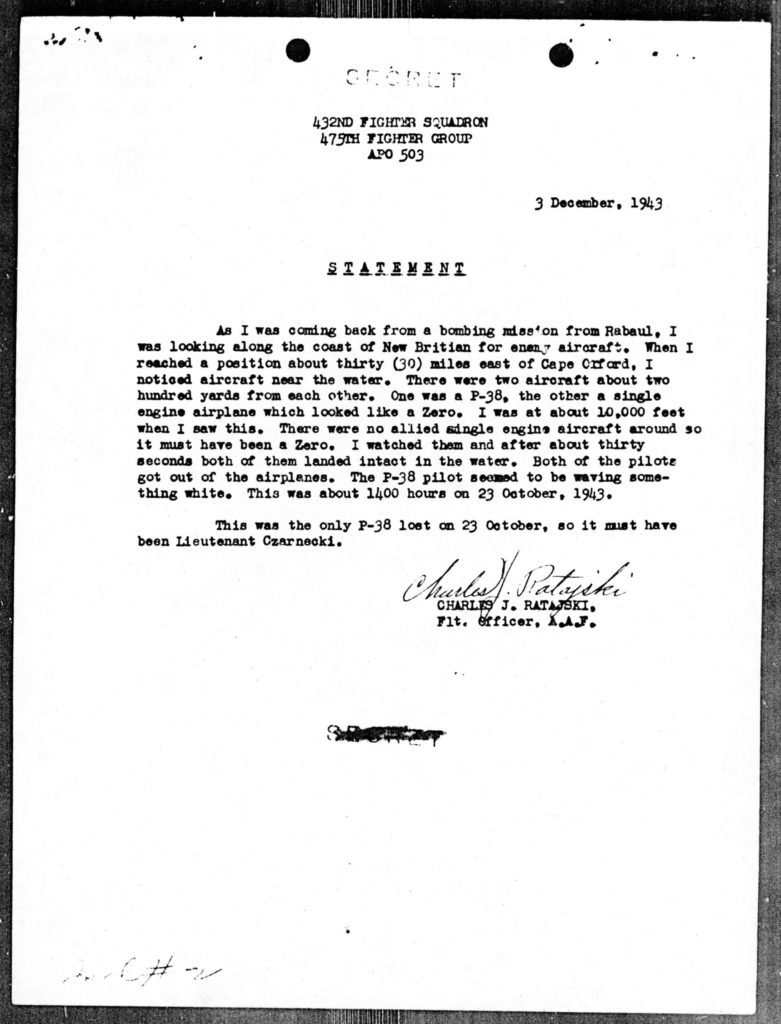

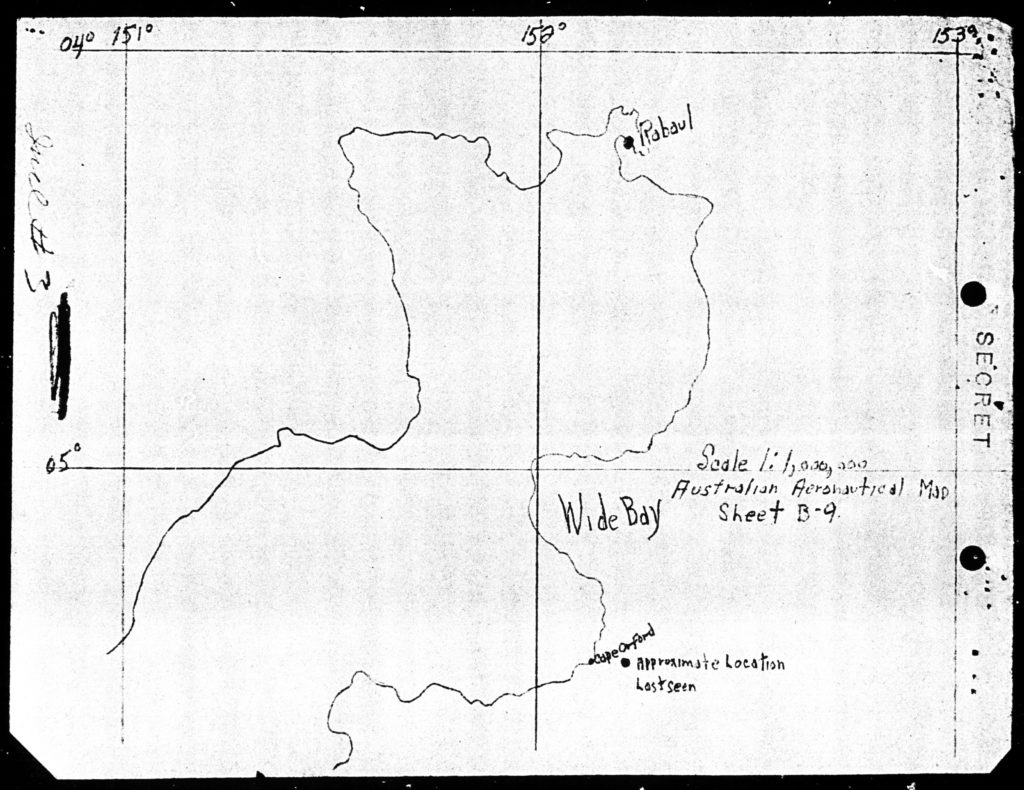

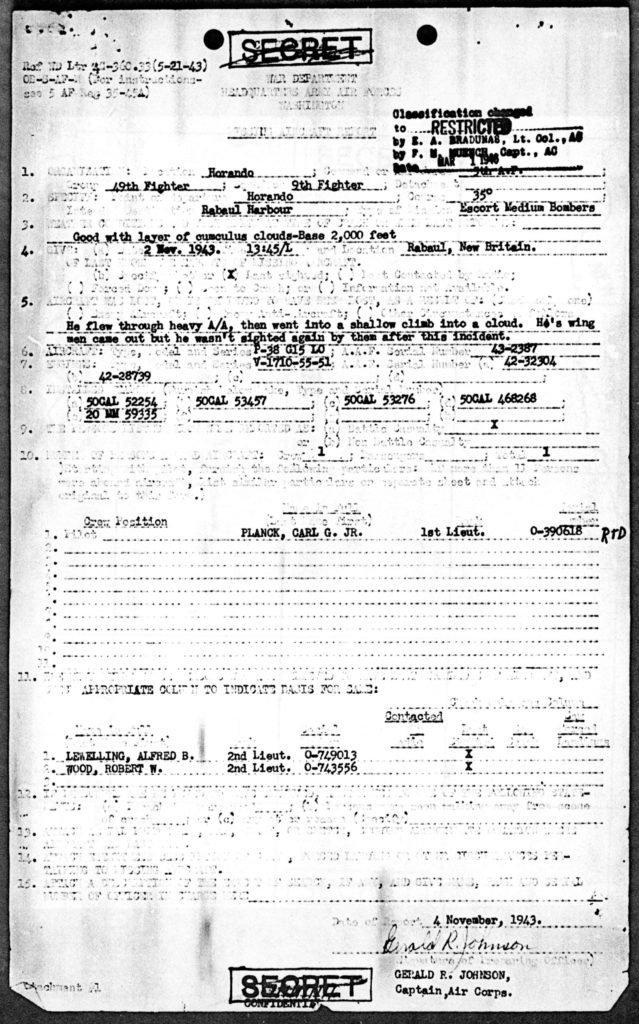

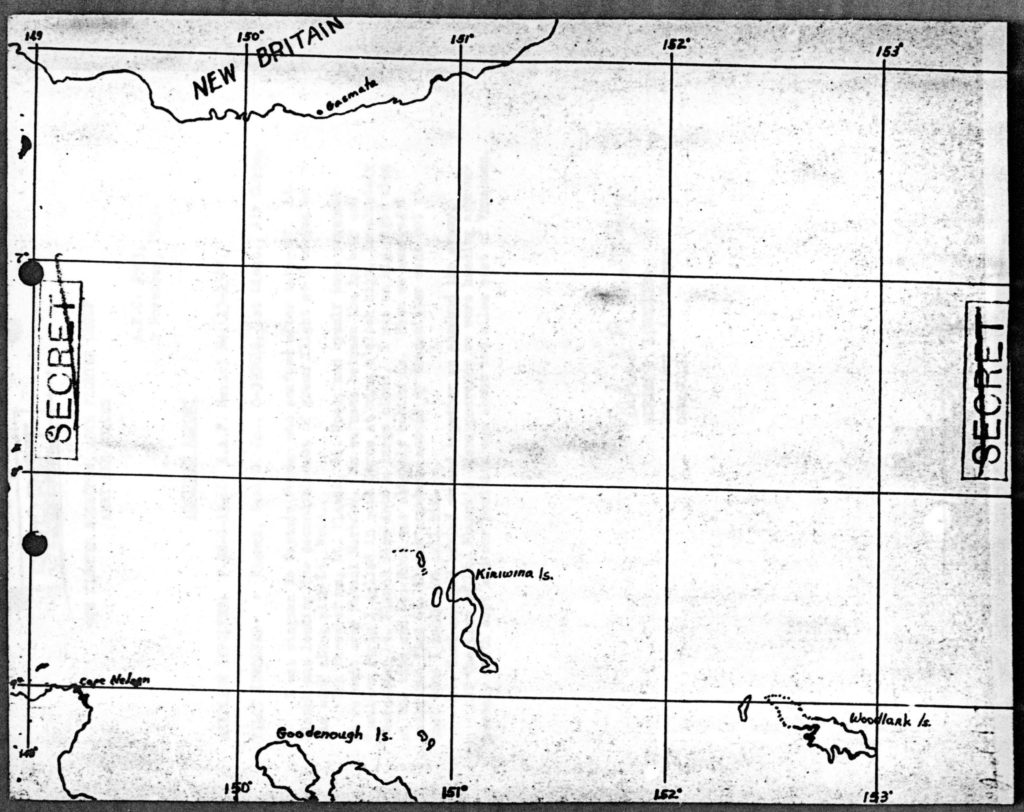

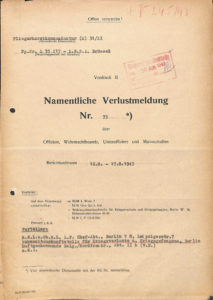

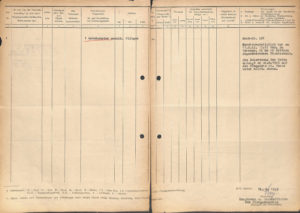

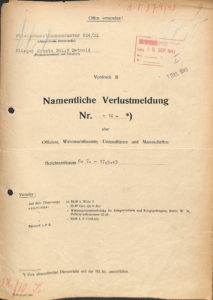

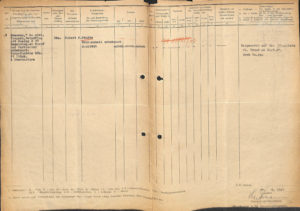

MACR 1235 for P-38H 42-66849 and Lt. Planck, missing on October 23, 1943. These digital images were scanned from paper photocopies which were themselves made from a fiche copy of the MACR.

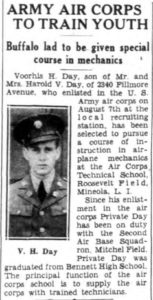

Edward Czarnecki’s name appeared within a list of military casualties published in The Philadelphia Inquirer on November 28, 1943. Since northern Delaware and southern New Jersey were (still are) within the Inquirer’s primary geographic area of news coverage (…not that I actually r e a d the Inquirer…I don’t…but that’s off topic…), the names of military casualties from Wilmington, Delaware, the vicinity of Camden, New Jersey, and southern ‘Jersey “in general” not uncommonly appeared in the newspaper.

The image below shows “setting” of the above article: Page 2. Unlike The new York Times, where WW II casualty lists – regardless of length – appeared several pages well “into” the body of the newspaper, WW II casualty lists in the Inquirer always appeared or at least commenced on the paper’s first or second pages. As the war progressed and casualty lists inevitably became longer, the “first” part of most lists would typically appear “below the fold” on the newspaper’s front page, and continue a few pages into the body of the paper.

The timing of publication this particular list is actually typical of the appearance of most WW II casualty lists in the (then) print news media: There was usually (usually…) about a month time lag between the date on which a serviceman was killed, wounded, or missing in action, and the appearance of his name within Casualty Lists released by the War Department. Thus, a little over one month transpired between Czarnecki’s shoot-down on October 23, 1943, and his name’s appearance in the Inquirer on November 28.

________________________________________

First Lieutenant Carl G. Planck

9th Fighter Squadron, 49th Fighter Group, 5th Air Force

Here’s Lt. Planck in an official Army Air Force (undated, but obviously (!) pre-November 1, 1943) photo (122747AC (A32518)). Caption: “A member of the United States Army Air Force fighter squadron that destroyed seventy-two Japanese planes in aerial combat in New Guinea from June 1, 1942 to January 8, 1943 shortly after the fall of Buna Mission, is shown here. He is Second Lieutenant Carl G. Planck, 8 Sutherland Avenue, Charleston, South Carolina, with one confirmed victory.”

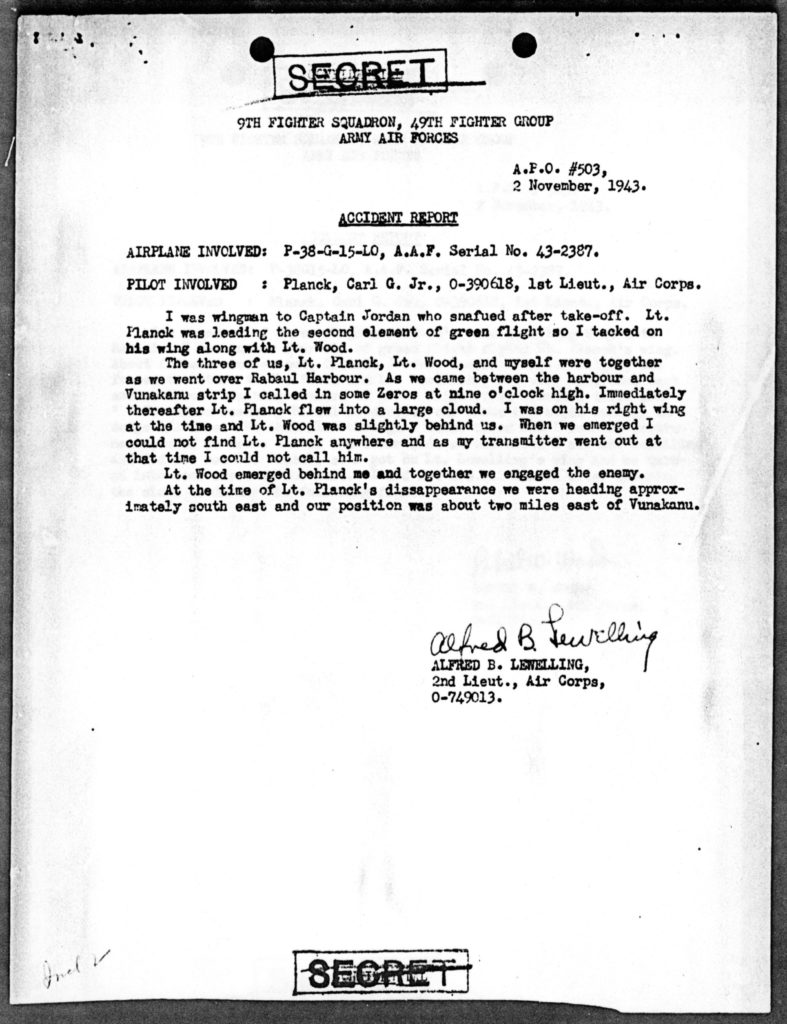

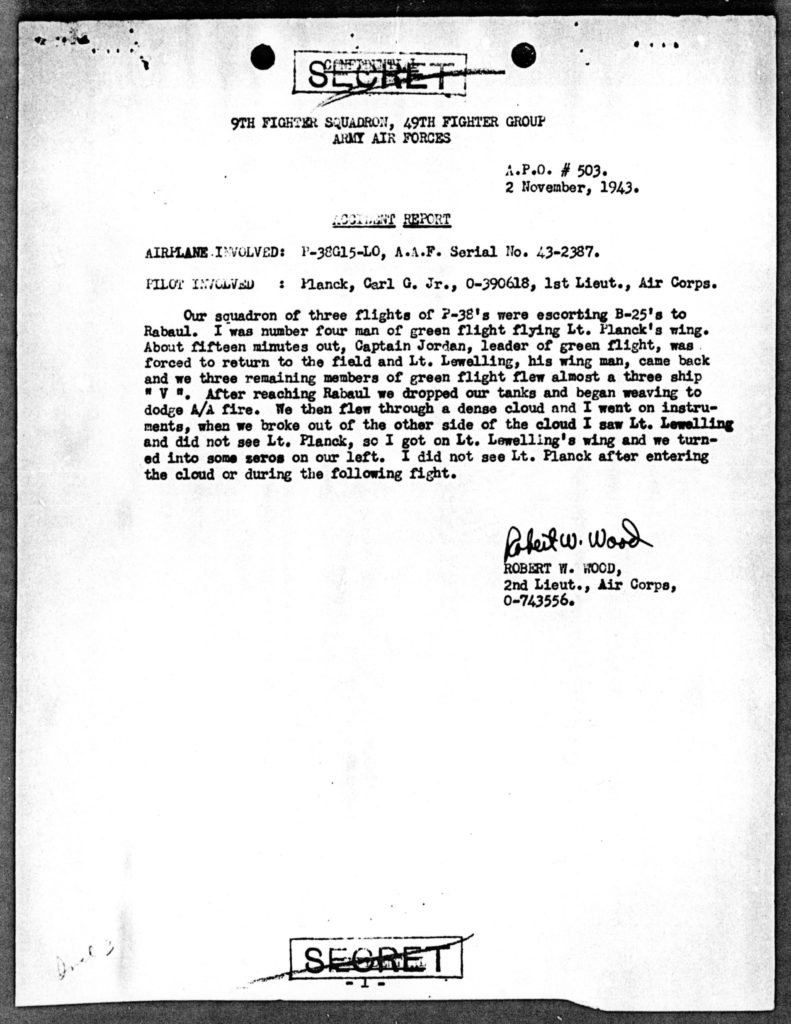

MACR 1016 for Lt. Planck and P-38H 43-2387, missing on November 1, 1943. Akin to the MACR for Lt. Czarnecki, these digital images were scanned from paper photocopies, made from fiche.

Carl G. Planck, at Pacific Wrecks

P-38G 43-2387, at Pacific Wrecks

________________________________________

First Lieutenant Raymond K. Hine

339th Fighter Squadron, 347h Fighter Group, 13th Air Force

Operation Vengeance – the aerial interception and killing of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto by P-38 Lightnings of the United States army Air Force (specifically, the 339th Fighter Squadron of the 347th Fighter Group) on April 18, 1943 – has continued to be the subject of a vast amount of attention, commentary, and study. I myself first learned about this story in the Ballantine Books’ paperback Zero, by Masatake Okumiya, Jiro Horikoshi, and – a h e m – Martin Caidin, where the story is covered in Chapter 20. Appropriately headed “Admiral Yamamoto Dies in Action”, the events of that day are presented from both (primarily) the Japanese, and (secondarily) the American vantage points. Therein, in terms of American losses, is found the simple statement, “Our pilots shot down Lieutenant Ray Hine’s P-38; and, we verified later most of the fifteen P-38s which returned to Guadalcanal were badly shot up.” Regardless of the degree of accuracy in the account given in Zero, I was struck by the irony – for lack of a better word – of Hine being the only American pilot not to have returned from the mission. And then, years later, I found his photograph in NARA RG 18-PU. “So, that’s who he was…”

This portrait of Raymond Hine was taken at Kelly Field on September 29, 1941. Two additional portraits of him (one of which also appears at Pacific Wrecks) at can be found in his biographic profile at FindAGrave.

1 Lt. Raymond K. Hine, at FindAGrave

1 Lt. Raymond K. Hine, at PacificWrecks

1 Lt. Raymond K. Hine, at Historynet