“Just before sundown, rain began falling, the wind became stronger, and the waves got higher and higher. There wasn’t much I could do – I was still weak and not a little scared. About all I did was to throw out my sea anchor – a small rubber bracket on a 7-foot line – and cover myself with my sail. Rain fell in torrents and the wind blew all night. I bailed out water six or seven times during the night with the small cup that the pump fits in and also with my sponge rubber cushion, but there were always 2 or 3 inches of water in the bottom. The rest of the time, I just huddled under my sail.”

________________________________________

The posts about the survival and return of Lieutenants Johnson and Landers pertaining to events in 1942, this post focuses on the experiences of Navy Lt. JG William Robert Maxwell in mid-1943. A member of Navy Fighter Squadron VF-11, Maxwell was not shot down in aerial combat, per se, albeit he was forced to parachute during a combat mission. This occurred on May 2, 1943, during his squadron’s first week of combat operations, when, while escorting a strike to Munda, his F4F Wildcat’s tail was sliced off by his wingman as the latter was switching fuel tanks. Successfully parachuting from his fighter, Maxwell took to his life raft, in time successively reaching the islands of Vangunu, Tetepare (Tetepari) and Rendova, being rescued from the latter on May 17.

While one commonality among the experiences of these three aviators is that they saved themselves by parachuting from their planes (rather than belly-landing or ditching their aircraft), another, more critical element, with I think greater relevance to survival and evasion – notably with Johnson and Maxwell – is that the very circumstances of their predicaments forced them to be self-reliant during much (Maxwell), or all (Johnson), of the time until their rescue. (Landers didn’t have that problem, meeting native tribesmen very soon after landing!) On the other hand, a central difference between the Army Air Force pilots and Maxwell is that a life raft was absolutely central to the latter’s survival – at sea. Landing on land, neither Johnson nor Landers had no such problem. (Well, Johnson had other problems!)

Some time after his return, Maxwell wrote a detailed account of his experiences and survival, which was published in Intelligence Bulletin of December, 1943 (available at Archive.org). As you can read below, where I’ve presented the article verbatim, Maxwell’s account has absolutely no identifying information (well, it was the middle of the war!) except for the calendar dates, and particularly, the first date – May 2 – when he was shot down. Using this information, DuckDuckGo, and various websites (like Aviation Archeology) I was able to “pin down” the initially anonymous pilot’s name, identity his Squadron, and determine the Bureau Number of his F4F. That led to Tillman and van der Lugt’s VF-11/111 ‘Sundowners’ 1942–95, which tied all the pieces together, the details matching the account in Intelligence Bulletin.

Digressing… Like many “things” one discovers while doing historical research, I found this article, and the journal itself, purely by chance: While researching a post covering a subject vastly different from WW II (albeit quite military in nature) … and then some! Space Warfare, as described and conjectured in Astounding Science Fiction, in 1939.

So, it would seem that researching fiction led to fact.

__________

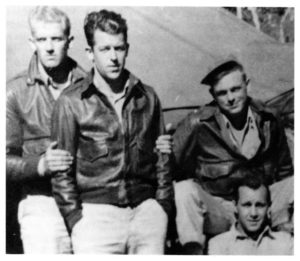

William Robert Maxwell later in WW II, probably while serving with VF-51.

__________

This is the relevant passage excerpt from Tillman and van der Lugt’s VF-11/111 ‘Sundowners’ 1942–95:

On 25 April 1943, after six weeks in the Fijian islands, CAG-11 departed for Guadalcanal. White, Cady and Vogel each led one of VF-11’s three elements to their destination, with TBFs providing navigation lead on the 600-mile flight. The Wildcats made the 4.5-hour flight to Espiritu Santo that day and logged another 4.3 the next, arriving at ‘The Canal’ on Monday the 26th with 34 aircraft. Two had been delayed en route with mechanical problems, but both shortly rejoined the squadron. ‘Fighting 11’ settled down at the Lunga Point strip better known as ‘Fighter One’, while Cdr Hamilton’s other three squadrons were based at nearby Henderson Field. The ground echelon had previously arrived by ship or transport aeroplane and established a tent camp in what intelligence officer Lt Donald Meyer called ‘a delightful oasis of mud and mosquitoes in a coconut grove’.

The next day VF-11 was briefed by Col Sam Moore, the colourful, swashbuckling Marine fighter commander. The ‘Sundowners’ were to fly under the tactical control of the US Marine Corps, as the leathernecks had been operating from the island for the past eight months. Later that morning (the 27th), VF-11’s first patrol from ‘Cactus’ was flown by Lt Cdr Vogel and Lt(jg)s Robert N Flath, William R Maxwell, and Cyrus G Cary. It was a local flight with nothing to report, but two days later Lt Cdr White led two divisions on an escort to Munda. The only enemy opposition was anti-aircraft (AA) fire. Throughout the combat tour VF-11 was blessed with exceptional maintenance. Prior to any losses, the unit maintained an average 37 of 41 available aircraft fully operational for an initial complement of 38 pilots. The 90 percent readiness rate was partly due to the Wildcat’s relative simplicity, but it was also a tribute to Frank Quady’s maintenance crew. The ‘Sundowners’’ mechanics certainly deserved their reputation, as they literally built an extra fighter from the ground up. Using portions of three or four Marine wrecks, the sailors assembled another F4F-4 which they assigned the BuAer number 11!

At the end of the first week (Sunday, 2 May) VF-11 suffered its first loss. Sixteen ‘Sundowners’ were escorting a strike to Munda when, south of Vangunu, at 14,000 ft the ‘exec’, Sully Vogel, ran one of his fuel tanks dry and lost altitude while switching tanks. His element leader, Bob Maxwell, moved to port to regain sight of Vogel and the two Wildcats collided. Vogel’s propeller sliced off the last six feet of Maxwell’s fuselage (BuNo 11757), the F4F nosing up in a half loop and then falling away in a flat spin. Maxwell managed to bail out and opened his parachute, but the other Wildcats had to continue the mission. At 1700 hrs the returning pilots spotted Maxwell in his life raft and reported his position, although it was too late to summon help. Vogel had aborted the mission, returning with a smashed canopy and rubber marks on one wing from Maxwell’s tyres. ‘Maxie’ was nowhere to be seen the next morning, and he remained missing for a full two weeks until a PBY Catalina brought him back to Guadalcanal on 18 May after a harrowing, but safe, 16 days in enemy-occupied territory. The intrepid South Carolinian had sailed his raft to Tetipari, arriving on the 5th. He walked the length of the island in seven days, encountering a crocodile that claimed dominion over a channel on a coral beach, but otherwise Maxwell met no opposition. On the 13th he launched his raft for Rendova, where he knew he might contact an Australian coast watcher. He was met by friendly natives who took him to safety near Segi Lagoon on the 17th.

__________

This Oogle Map shows the Solomon Islands. Vangunu, Tetepare (Tetipari), and Rendova are situated in the “center”, as it were, of the archipelago.

__________

Here’s a closer Oogle Map view of Vangunu, Tetepare (Tetipari), and Rendova.

__________

Finally, an air photo / satellite view of the same three islands. (This image is from Duck Duck Go, not Oogle.)

__________

Also from Tillman and van der Lugt’s VF-11/111 ‘Sundowners’ 1942–95:

Maxwell’s fifth mission had been his last with VF-11, for he was flown to New Zealand, where he spent the next spent two months in hospital, recuperating from his adventure. Subsequently he joined VF-51, becoming the squadron’s only ace aboard USS San Jacinto (CVL-30) in 1944.

__________

The original source of Maxwell’s report: Intelligence Bulletin for December, 1943, from Archive.org.

__________

And so, here’s Robert Maxwell’s report…

Section III. A CASTAWAY’S DIARY

1. INTRODUCTION

A U.S. aviator, forced to parachute from his plane in the South Pacific, spent two trying weeks on the sea and on practically uninhabited islands before he was rescued. He kept a day-by-day account of his experiences, relating how he utilized his equipment, the mistakes he made, and how he obtained food and water.

A condensed version of this pilot’s diary is presented below. In addition to being interesting, his story is believed to contain lessons which will be profitable for other members of our armed forces. It is considered that the safe return of this pilot to his squadron should be attributed to his resourcefulness and the intelligent use he made of his equipment. The fact that he knew where he was and where he wanted to go, and knew how to go about getting there saved him from a great deal of futile wandering and mental distress.

The names of persons and places have been omitted from the story.

2. THE DIARY

May 2 [1943]

The opening of the ‘chute snapped me up short, and I was able to look around and see my plane falling in two pieces – the tail section and about 6 feet of fuselage were drifting crazily downward and the forepart was fluttering down like a leaf. I tried to ease the pressure of the leg straps on my thighs by pulling myself up to sit on the straps, but was unable to do so because of the weight and bulk of my life raft and cushions. As a result, my thighs were considerably chafed.

I was so busy looking around that I didn’t notice how fast I was descending, and before I knew it I had hit the water. The wind billowed the ‘chute out as I went under, and I was able to unfasten my chest strap and left leg strap at once; unfastening the right strap took about 45 seconds, and I held on to the straps as I was pulled along under water by the ‘chute. I couldn’t understand why I didn’t come to the surface – then I remembered that I hadn’t pulled the CO2 (carbon dioxide) strings of my life jacket. As soon as I had done this, my belt inflated and I came to the surface. I immediately slipped my life raft off the leg straps, ripped off the cover, and inflated it.

During my descent I had hooked an arm through my back pack strap so as not to lose it, but during the time I was struggling under water it must have come off because, when I came up, I saw it floating about 20 feet away. I paddled over and picked it up, along with two cushions – one of which was merely a piece of sponge rubber, 15 inches square and 2 inches thick.

After I got into the boat, I took the mirror from the back pack and discovered a deep gash, about 14 inches long, on my chin and another deep gash, about 3 inches long, on my right shin. I took out my first-aid kit, examined the contents, and read the instructions. I found that there was no adhesive tape in the kit – apparently it had not been replaced when the kit was checked on the ship coming down from Pearl Harbor. I sprinkled sulfanilamide powder on both wounds and put one of the two compress bandages on my leg. I haven’t any idea how I got either one of these cuts. During this time I was having brief spells of nausea, but did not vomit. However, in a short while I had a sudden bowel movement, probably as a reaction from the shock and excitement. I felt very weak and dizzy.

I began to take stock of my equipment and to figure out where I was by consulting the strip map which I had in my pocket. My chief aim was to reach the nearest land.

As I sat in the boat, still dazed and faint, I realized that, with the distance and prevailing northeast wind, I had little chance of making one of the larger islands. As nearly as I could figure out, I was about 10 miles east of a small island and about 10 or 15 miles south of another. Beyond reaching land I hadn’t formulated any plans except to reach land.

About 50 minutes after I had crashed, I saw a friendly fighter coming toward me from the west, about 50 feet off the water. I immediately grabbed my mirror and tried to flash the plane. The pilot wobbled the plane’s wings, came in, and circled, and I saw that it was my wing man. Five other fighters came down and circled, apparently trying to get a fix on me, and I waved to them.

Soon they went off toward the cast, and I noticed to my consternation that dark cumulus thunderhead clouds were moving in quickly from the northeast and that the sea was getting quite rough. I realized that no planes would come out for me then because of the approaching dusk. Just before sundown, rain began falling, the wind became stronger, and the waves got higher and higher. There wasn’t much I could do – I was still weak and not a little scared. About all I did was to throw out my sea anchor – a small rubber bracket on a 7-foot line – and cover myself with my sail. Rain fell in torrents and the wind blew all night. I bailed out water six or seven times during the night with the small cup that the pump fits in and also with my sponge rubber cushion, but there were always 2 or 3 inches of water in the bottom. The rest of the time, I just huddled under my sail.

May 3

The rain stopped about daybreak, but the sky was cloudy and the sea still choppy. Off to the east I saw what appeared to be two friendly fighters in the distance, but I knew they wouldn’t see me. As day approached, I saw that I had been blown about 10 miles south of the center of the island I was making for. The, wind was still from the northeast and I knew I would have to paddle like the devil even to hold my own and not be blown farther out to sea. I broke out one of my six chocolate bars and ate part of it, but I wasn’t hungry. I also took a swallow out of my canteen, but I wasn’t particularly thirsty. All day long I rowed with my hand paddles, sitting backward in the raft. By 1600 my forearms were raw and chafed from rubbing against the sides of the raft. I had stopped paddling only two or three times during the day, to eat a bite of chocolate and take a swallow of water. Rain began falling about 1600, and I hit a new low point of discouragement when I realized that I had apparently made no headway at all during the day.

After night fell, the rain continued in intermittent showers until dawn. The sea was still rough and the wind was from the northeast. I tried to continue paddling, but a large fish hit my hand – I don’t know what kind it was – in fact, I didn’t even see it, but the experience dissuaded me from rowing any more in the dark. I threw out my sea anchor again – this time with the two cushions tied on the line for additional weight – and huddled under my sail for the rest of the night. I don’t recall that I slept this night, or any night before I got to shore – I just seemed to lie in a sort of coma.

May 4

When the sun came up, I found that I was south of the west end of the island and about two miles farther out than I had been the previous morning. I broke out another chocolate bar for “breakfast,” drank a little water, and began to paddle again. Some time during the day I got the idea of getting in the water and swimming along with the raft. The only result of this maneuver was that I lost one of my hand paddles, and I went back to paddling with the remaining paddle and my bare hand.

The results of my continuous paddling were more heartening this day, and by about 1500 I realized that I had covered quite a little distance. Just about this time, however, a big storm came from the northwest, and it began to rain again. Again I put out my sea anchor with the cushions tied to it, and settled down under my sail. It rained off and on all night with a northwest wind. Although I was never very thirsty, I would catch rain on my sail and funnel it into the pump cup, drink some of it, and use the rest to keep my canteen filled. Before the storm came that afternoon, the sun had been quite hot and I had kept my head covered with my sail and applied zinc oxide to my face. Earlier that day I had seen four friendly fighters, going west along the south shore of this island. I also saw a friendly patrol plane which passed over early every morning and late every evening, but because the sun was so far down each time, I was never able to signal with my mirror.

May 5

At daybreak I saw that I had drifted to a point about 6 miles south of the east end of the island. I had another chocolate bar for breakfast and a little water, and I was considerably encouraged when I found that the wind was blowing from the southeast. This meant that I had a very good chance of reaching the island, so I pulled in my sea anchor and began paddling. Some time during the morning my remaining hand paddle slipped off in the water and, forgetting that I had my life belt inflated, I jumped overboard to retrieve it. Of course, I couldn’t get under the surface and soon gave up.

I stopped paddling only to take an occasional swallow of water, and about 1800 I came close to the shore. The surf didn’t look too bad. I headed right in – a mistake, as it turned out, for as soon as I got in closer I found that the waves were at least 50 feet high (*), the highest surf I’ve ever seen. About this time a big one broke.in front of me. It was too late to turn back. I felt as if I were 50 feet in the air when it broke, and all I could see in front of me was the jagged coral of the beach. I tried to beat the next one in, but it caught me just after it broke and tossed me end-over-the-kettle into the coral.

Fortunately, I missed hitting the sharpest coral and received only a few cuts on my hands. My boat landed about 50 feet away in a sort of channel leading into the beach. I tried to stand up and found that I couldn’t walk. Finally, I crawled over to the little channel, got my boat, and dragged it up on a small sandy beach. Since I had tied my belongings rather securely to the raft, the only items that were missing were the pump, the two cushions, and the can of sea marker. I was very tired and very weak; I turned my raft upside down and lay on it, with my sail over me, trying to sleep, but apparently I was too tired to sleep – I think I only dozed for periods of a few minutes at the most.

May 6

At dawn I began to look for coconuts on the ground and found one mature nut under a tree. The tree was about 25 feet high, and I immediately set to thinking how I could get more of the nuts off it. I was, of course, too weak to climb and I thought of cutting notches in the tree. It was hopeless, and I opened the one coconut. The seed had already sprouted and there wasn’t much milk in it; since I wasn’t hungry, I ate only a little of the meat.

Instead, I had my usual “breakfast” of a chocolate bar, laid out my things to dry, cleaned my knife and gun as best I could, and rested some more. Although my .45 had been wet almost constantly and was quite rusty, the moving parts worked all right after I had applied more oil to them.

Then I started out to find some pandanus nuts, having read and reread my guidebook. I found a few, but they were so high I couldn’t get to them. In the afternoon I sorted my equipment and rested. By this time I had decided to try reaching the western end of the island. I wasn’t sure whether there were any Japs or natives on the island, but thought I might at least run into some natives.

During the day I ran across a crocodile in a channel in the coral beach, but we parted company at once, without incident. Toward evening, rain threatened. I made a coconut cup, imbedded it in the sand, and rigged my sail around it so that it would catch water and funnel it into the cup through a small hole in the sail. The rain began when it got dark. I settled myself on the ground under a tree and pulled my rubber boat over me for shelter.

May 7

In the morning I worked out a plan for getting some coconuts. I cut several notches in the trunk of the tree and then made a sort of rope ladder with my sea anchor line, placed this around the trunk so that it would slip, and pushed it up as far as I could. Climbing up by these means, I was able to reach and twist off two coconuts. This was pretty exhausting work, so I rested for a while and then filled my canteen with the rain water that had accumulated in the coconut cup. I drank the milk from the coconut and ate a little of the soft meat, but still I was not very hungry. My store of chocolate bars was down to two, so I decided to conserve them.

I then packed all my gear in my back pack, rolled up my life raft, and set out to walk along the coast to the west end of the island. There was a 100-yard stretch of coral between the water and the beach, and it was not bad walking. Naturally, I was glad I hadn’t discarded by shoes in the water. Several times I came to channels in the coral, usually at the mouths of small streams, and then I would have to blow up my life belt and swim across. At one such “place I saw more fish and tried to catch one with my fishing line and pork-rind bait, but the fish declined to bite.

Late in the day I came to a sandy beach, along which I walked until it was dark. Then I made a crude lean-to of palm fronds against a tree trunk, blew up my life raft, and settled down on it with my sail as a cover. I smeared zinc oxide on my face – I put either zinc oxide or vaseline on my face each morning and night for protection against sunburn, and also periodically put vaseline on the gash on my shin and on my hands, which were cracked from the salt water. The sulfanilamide powder was rather water-soaked, so I used vaseline instead. Aside from a daily quinine pill, that was the extent of my doctoring. Fortunately, the gash on my chin had closed pretty well.

That night I woke up from one of my periods of dozing to find that the tide had come in. I scrambled around, moving my gear to a dry spot, and discovered that the tide had carried away my sail and my shoulder holster. Luckily, I had my .45 close to my side, but one of the two clips in the holster contained all my tracer bullets.

May 8

In the morning, after I had eaten half of my remaining chocolate bar, I started walking again. Most of the time I walked in the water up to my knees. Soon the coral ledge ended and I had to strike inland because I couldn’t get through the immense surf that was washing against the high rock and coral of the shore. I would go inland a little way, parallel the coast by clambering up and down the ridges, and then go back to the shore to see if I could make my way along it. During the day I saw two more crocodiles in a small lagoon and my only snake, a small blue snake about 1 1/2 feet long with a flat tail. During the day I found several coconuts along the beach and on the ground, and I drank the milk. As dusk came on, I was inland, climbing one of the ridges. It began to rain. I put my life jacket and back pack on the ground, under a log, and lay on my deflated life raft. It rained all night, and by morning I was lying in mud.

May 9

During the morning I crossed more ridges, which ran down to the shore from the central range. This was pretty tiring – mostly I would zigzag up them, and then slip and slide down. I was always hopeful that I would be able to make my way along the coast, but this was impossible. During the day I ate some fern leaves and the remainder of my last chocolate bar. At dusk I came down to the coast to see whether I had rounded a particular rocky point. I found that I hadn’t, and decided to spend the night in a small cave in the coral, which was about 100 feet above and 150 feet back from the water. I slept on my back pack and life jacket and used my deflated raft as a cover. After sleeping spasmodically, I was awakened at dawn by a wave breaking at the entrance to the cave.

May 10

In the morning, rain was falling and the wind was blowing; I could make little headway over the rocks and coral so I took to the ridges again. I ate some ferns, and about 1450 I came onto the shore where there was a good sandy beach. The hills were smaller, and there was a grove of coconut palms. I was near the end of the island and could see the next one about 2 or 3 miles across the channel. In the shallow water I found two small crabs and about eight mussels. I ate the crabs raw, and, putting the mussels in my pocket, headed for a small bay. It was a fine afternoon and I built a lean-to of sticks and palm fronds and blew up my raft. I then tried some of the mussels and found that they were rather unpleasantly slimy. When I ate the rest the next day, I washed them first and they tasted pretty good. It rained that night, and since my lean-to did not prove to be as water-proof as I had expected, I got under my boat.

May 11

The next morning I rested, and ate the meat and drank the milk of a few coconuts. I decided not to build a fire because of the possibility of attracting Japs, but to get to the next island and try to make contact with the natives. I filled my canteen from a stream. Late in the afternoon a number of friendly bombers and fighters came over going west and soon returned. Both times I used my mirror to try to attract their attention. I was quite weak and tired, but built a new and better lean-to. That night I dozed fitfully and the mosquitoes were quite annoying. The only other noteworthy incident that day was my first bowel movement since the one immediately after parachuting into the sea.

May 12

In the morning I washed my clothes and set about making some oars. I found two small pieces of lumber with a few nails and a screw in them, and, using the nails and a screw, I attached two sticks to the pieces of lumber to make a serviceable pair of oars. Then I ran my sea anchor line around my boat through the rings, and attached to it another piece of rope that I had found. I made two loops in the rope for oar locks. By looping the rope around my feet I could get leverage for rowing. I used some sponge rubber from my back pack to make pads for oars. I slit my back pack and inserted a couple of sticks; this provided me with a sail. When I had completed my preparations in the evening, I gave my craft a brief shake-down cruise, dined on coconuts, and went to sleep.1

May 13

With the meat of two coconuts and my canteen of water as provisions, I set out early in the morning on my voyage to the next island. I went out to sea through a break in the reef and soon found that, although my course was due west, I was heading northwest. This was due to a north-northeast wind, and I rowed constantly because of the possibility of being blown south Of the hook of the island. About noon I headed into a sandy beach on the south shore of the hook and again found to my dismay that I had underestimated the size of the surf. The waves caught me and tossed me onto a fairly smooth coral ledge. I was under water for what seemed a very long time – actually about 45 seconds – but managed to hold onto my boat. As I struggled to my feet I heard someone shouting and was overjoyed to see two natives in a canoe about 50 yards off shore waving to me.

I got into the canoe with all my gear except the back-pack cover and we started east to the south shore of the point, where we met two more natives in another canoe and put into the beach. The natives brought some water and a taro from a hut. After a while we started around the point and along the shore. The natives asked me if I were thirsty, and when I said that I was, we again put into the beach and went into another hut, where I saw a collapsible Japanese boat. One of the natives climbed a 50-foot coconut palm and brought me some coconuts.

Finally we pushed on to a village about halfway up the coast. There I was greeted by the chief. After being given pineapple and taro, I was taken to another hut where it was indicated that I was to sleep. I was given a corner of a low platform, a clean bamboo mat, and a pillow and blanket. After eating more pineapple and taro, I talked mostly with the chief’s son, who had been to a mission school and was quite interested in America. After dark we all went to sleep.

Traveling from island to island for three days, the natives managed to get me to the U.S. outpost, where I was picked up and carried back to my organization.

(*) This height, estimated by the writer, is believed to be excessive.

References

Intelligence Bulletin, V II N 4, December, 1943, Military Intelligence Division, War Department, Washington, D.C.

Tillman, Barret; van der Lugt, Henk; Holmes, Tony, VF-11/111 ‘Sundowners’ 1942–95 – Aviation Elite Units 36, Osprey Publishing Company, London, England, 2012