The appearance of Willy Ley and Malcolm Jameson’s articles about Space War in the August and November issues of Astounding Science Fiction for 1939, generated – unsurprisingly – a small fusillade of laudatory comment in the magazine in its issues of October and December, 1939, and May of 1940. The contributors were Thomas S. Gardner of Kingsport, Tennessee; A. Arthur Smith of Ontario, Canada; J.M. Cripps of Manhattan, Kansas; James S. Avery of Skowhegan, Maine, as well as Jameson and Ley themselves, in the October and May issues, respectively.

In the October issue, reader Gardner gives his evaluation of the literary merits of the August, 1939 issue, and follows with agreement about Ley’s article, albeit suggesting that “rays” might be safer weapons than projectiles, albeit not explaining how. Malcolm Jameson’s letter provides insight into his career in the Navy. Then, he segues into the “core” of his own article, which pertained to locating, tracking, and aiming at an enemy spacecraft. He also addresses the technology of guns, or more accurately, cannon, in terms of the weight (mass) of the gun itself, qualifying this with the realization that his comments pertain to guns in terrestrial conditions, not space.

Reader Cripps, in the December Astounding, turns out to be an advocate of “rays”, under the proviso that, “if you [Willy ley] admit-their scientifictional credibility, it won’t strain you too much to realize that there is just a possibility that those same projectors might not be either so weak or so sensitive to shaking or jarring as you seem to think.” He premises this on the assumption that spacecraft can be propelled – be powered and reach escape velocity; leave a planet’s gravity well – solely by means of “ray projectors”, rather than, “the sort of chemical rocket that can he designed today.” In this context, he suggests that energy released from a cyclotron could be transformed into electricity and then projected into space via a “ray generator” or “refractory projector”, without (!) expanding onto how said generator or projector is specifically to function.

Well, feasible or not, it’s interesting to think about!

As for addressing Willy Ley as “Herr Ley”? Whether that is a sign of respect, or something else again, will remain unknown…

In the issue of May, 1940, reader Avery’s comments parallel those of Gardner in 1939, addressing the magazine’s literary content, and positing a question concerning Jameson’s analysis of a spacecraft versus spacecraft battle. Then, Willy Ley explains his advocacy of guns versus “torpedoes”, by focusing on the suitability of 37 and 75mm canon, specifically in terms of the weight of the former. As for the “37”, “…that they are effective enough has meantime been demonstrated by the new 37-millimeter anti-tank guns of the U.S. army that “disintegrated” 1 ½-inch steel armor plate at a thousand yards without a moment’s hesitation. That 1,000 yard range means, of course, in air – for space conditions it might safely be multiplied by a hundred or even more.” Perhaps so for space warfare. However, in terms of (terrestrial!) anti-tank combat, while the 37mm (M3) gun was a suitable weapon against pre-war tank designs, Japanese tanks throughout the war (in a general sense), and light (including German) German armored vehicles, it was not an effective weapon against the Panzer IV and later German tanks.

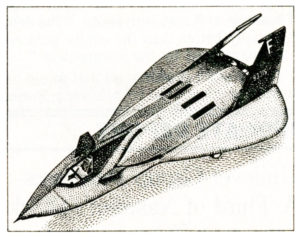

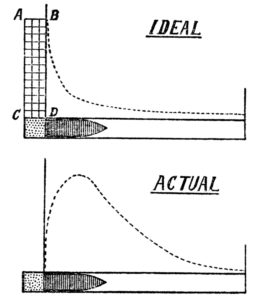

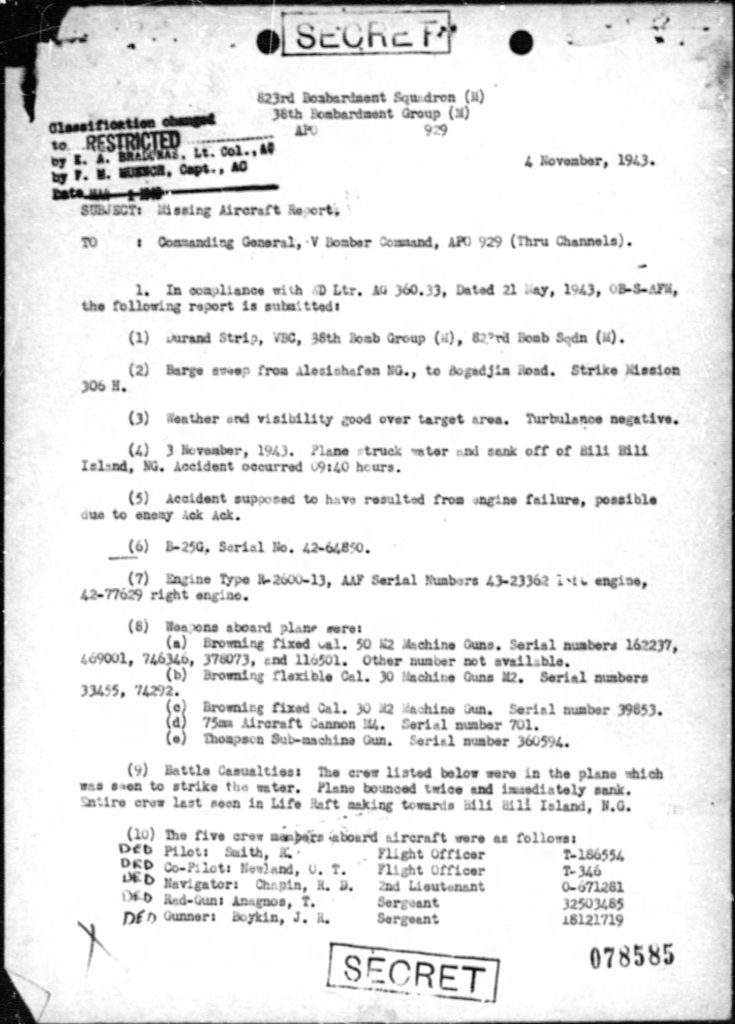

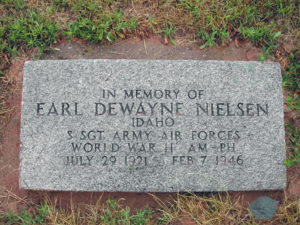

Anyway, to liven things up a little bit, included are images of the covers of the relevant issues of Astounding, those for October, 1939 and May, 1940, having been found on the Internet. There is also a lovely piece of black & white interior art, I’m certain by Henry Richard Van Dongen.

Astounding Science Fiction

October, 1939 (pp. 154-160)

Malcolm Jameson plans to expand on Ley’s ballistics!

Dear Mr. Campbell:

I regret to have to give Astounding Stories a very good rating for the August, 1939, issue. I repeat, I regret, because it is very difficult to keep up such a high standard as Astounding has been setting for the past six months. I am afraid that I will be disappointed one of these issues — although I know that you will do every-thing to prevent such a catastrophe. Now to business:

Cover – good. It strikes a note of action and force. I like the contrasting reds and darker colors.

Your little editorials are quite Interesting – in spite of the fact that sometimes I do not always agree. However, this month we agree.

“General Swamp, C.I.C.” Quite a good and logical story – parallels the American Revolution. Your characters are well drawn, and I am glad to see the individualism shown, for it is passing out in America now. Of course, it is harder to fight a war with people who are free individuals – as we found out in 1776.

“The Luck of Ignatz” – A good character, I should like to see more of this character.

“The Blue Giraffe” – Humor can be used well in s-f. and de Camp handles it best of any that I have seen.

“Pleasure Trove” – The type of story that made old Astounding under Clayton liked – scientales with a punch. Thanks for the breathing spell from the heavy stuff.

“Heavy Planet” – Good. A logical and well-handled situation.

“Life-Line” – Very plausible and better on the second reading. The doctor didn’t completely believe his own theory and proof until he failed to save the young couple – then he knew that his own time was about up and he couldn’t change the future. That was cleverly put in the story.

“Stowaway” – Fairly good story and a good poke of fun at Earthlings.

“An Ultimatum from Mars” – The best of Cummings that I have seen in a long time.

“Space War” – Fine. Willy Ley sure knows his engineering and some ballistics. The article was the best of its type for some time. He is dead right – guns are going to be really tough to handle in free space. The trouble is in hitting the object – a whole new science of ballistics will have to be worked out – something like the multiple body problem on a small scale.

Tell Ley that rays might be safer – it they are developed on a large scale due to their spreading – for space around a battle will be uninhabitable for long distances due to unexploded bombs, et cetera. Of course, the h.e. shells will travel far away if they don’t hit.

Inside Illustrations – I still like them O.K.

General make-up was O.K. So you see why I regret to have to give it such a good rating – for can yon repeat next month? I hope so. – Thomas S. Gardner, P.O. Box 802, Kingsport, Tennessee.

SCIENCE DISCUSSIONS

Malcolm Jameson is one of the country’s few real experts on really heavy guns.

Dear Mr. Campbell:

Up to now I have been one of the most inarticulate of your contributors, but Willy Ley’s “Space War” in the August Astounding, is like smoke in the nostrils of an old fire-horse – it starts me itching to hop into the ring with him for an unlimited bout where we can hurl back and forth the fascinating facts of ballistics – both interior and exterior – and drag in that other science that utilizes both of them and some other things – Fire-Control. Ordinarily, I approach your science articles with a good deal of deference and with appropriate modesty, but when anybody starts writing about ordnance he is on ground where I think I know my way around. It happens that I spent eight or nine of the best years of my life where ordnance was being designed, manufactured, tested and used – in gun factory and laboratory, at proving grounds and on warships, both in peace and war, and in the field with troops. So if I make bold to comment: on Mr. Ley’s article, it is because I feel that I am competent to do so.

Not that I mean to imply I have fault to find with it. On the contrary, I am all for him – barring a few minor points. I like his demolition of the heat-gun and ray-screen doctrines, and the way he sails into other fantastic gadgets. I am in thorough accord with his choice of propelled explosives as the most probably final weapon of future warfare. My chief criticism is that he did not go far enough. He tells us what projectiles will do to the hostile ship, but not how to find it and hit it. The problem of finding the enemy and maintaining contact long enough to hit him, considering the stupendous reaches of the void and the colossal speeds involved, seems to me to transcend all other considerations. But then, that is the subject matter for another article entirely.

It occurs to me, however, that readers of Astounding may be interested in some expansion of several of the things Mr. Ley mentions; and also I would like to take issue with him as to one or two of his statements. Merely to list and briefly describe the many known factors that enter into gunnery would require pages, so I will confine myself to a few of those touched on in the article.

He spoke of the retarding effect of the air in the rifle bore ahead of the projectile. I can cite an instance that illustrates that beautifully and it won’t be necessary to swamp you with graphs, formulae or statistics. When the battleship Mississippi went into commission, Dr. Curtis of the physics department of the Bureau of Standards was one of the experts who went with us to Cuba to hold her experimental battery tests. Among other things, he desired to measure muzzle velocity under shipboard conditions. M.V. determination up to that time had been done only at the Proving Ground where it was possible to fire the shell through two successive screens hung in front of the gun.

Dr. Curtis rigged two metallic fingers at the muzzle of the gun, protruding slightly above the bottom of the rifling grooves, and also stretched a wire across the bore opening. These were parts of two electrical circuits, each hooked up to oscillographs. The idea was that the nose of the emerging shell would break the wire, thus interrupting one current, and that the bourrelet, or rotating hand, would wipe the fingers and complete the circuit of the other, thus producing two wiggles on the oscillograph tracing. He knew, of course, the exact distance from the shell-top to the lending edge of the bourrelet.

The first readings were absurdly low and Dr. Curtis correctly guessed that it was because the outrushing air had broken his wire before the shell got there. He put in heavier wire. Then a steel rod. Believe It or not, it was not until he had worked up to an iron bar, of something like 3/8 of an inch by a couple of inches, set edgewise like a girder across the opening, that he found something that would stay there until the projectile emerged. Even at that he had trouble with its fastenings. Some breeze!

I note Mr. Ley’s complaint that designers simply do not pay attention to weight unless the question of transport is involved. I assure him he Is quite mistaken. If the guns of a battleship could be reduced in weight by so little as five per cent, it would mean the saving of many tons which could well be utilized for other purposes. Actually, other characteristics of the gun being equal, gun weights have steadily declined – due chiefly to improvements In steel-making processes, notably heat treatment. Presumably, the trend will continue as better methods and stronger alloys are found.

The reason for the present weight of guns is stark necessity. It takes a lot of metal to withstand a suddenly applied force of upward of twenty tons to the square inch. When he says that reducing the thickness of gun barrels shortens their service life, he is dead right. It shortens it all right – is likely to cut it down to one terrific and fatal blast. If he had had the opportunity as I had, of seeing many ruptured field guns lying on Southampton dock during 1917, he would not think the factor of safety overstressed.

As to the difference in thickness between a worn-out gun and a new one, it is almost imperceptible to the untrained eye. Gunners keep a careful record of the number of rounds fired and star-gauge their guns often, for that is the only way they can keep track of the erosion. A worn bore, and the wear may not exceed the thickness of this sheet of paper, permits the powder gases to escape past the projectile, thereby seriously reducing its velocity. It also fends to promote wobble in flight.

In the vicinity of the breech not only are the pressures greater, but the temperatures are terrifically high, and I suspect that the lining of the powder chamber and the face of the breech-plug is for a moment In a virtually molten condition. I witnessed a blowback once, through an infinitesimal hairline scratch on the seat of the gas-check seal. It was a brand-new 14” gun under proof and the breech of it was ruined. The gases escaping through that little hole blew I the metal out in a line spray, like butter under a blow torch. Of course, the speed of the leaking gases added vastly to the damage, but it must be hot in there.

I doubt very much whether a strictly non-recoiling gun is possible. The recoil begins much earlier than most people Imagine – shortly after the projectile has started moving within the barrel.

In regard to the “optimum” elevation of 45 degrees, I might say that that is the elevation that theoretically gives the maximum range. I have seen heavy guns fired all the way up to fifty degrees, but there is little gain in range after the upper thirties, and a progressively greater loss of control. The famous German long-range gun could only be effective against a target as large as the city of Paris. Hitting somewhere within a ten-mile circle is not an artilleryman’s notion of marksmanship.

As to streamlining, that has been tried but is not practicable for several reasons. However, that does not mean that the shape of the shell is unimportant. The “coefficient of form” is an important one; long-pointed shells travel farther than short blunt ones. Armor-piercing projectiles that have to be stubby are equipped with false noses for that reason.

Of course, I realize that all this quibbling is about Earthly conditions and is not very applicable to what happens in the void. I am writing only because It may be of interest to our fans. As to the extension of Space Warfare to take in such matters as scouting, range finding, tracking and spotting, I am very much tempted to break out as an article writer myself. Then Mr. Ley can slip in a new ribbon and do a little sniping of his own. – Malcolm Jameson, 519 West 147th Street, New York, N.Y.

Maybe you can use rays, at that!

Dear Mr. Campbell:

I want to make a few comments about the August number of Astounding.

First point is Willy Ley’s article on the weapons of space combat. Frankly, I’ll still stick to the flaming rays and scintillating screens; Mr. Ley’s argument against them starts off with a bit of a self-contradiction. On page 74 he states: “That they (ray projectors) do not exist now is immaterial; science-fiction is not only concerned with things that are, but also with things that might be.” And forthwith proceeds to argue them out of existence on the grounds that the equipment necessary to produce them would be so ponderous compared with present-day artillery as to make them impracticable. Come, come, Mr. Ley! Surely, if you admit-their scientifictional credibility, it won’t strain you too much to realize that there is just a possibility that those same projectors might not be either so weak or so sensitive to shaking or jarring as you seem to think.

You say the projector would need a power plant, and “power plants are notoriously heavy.” O.K. But it also appears to me that even an unarmed ship might need a fair-sized set of generators just to lift it into space; unless, of course, you insist on limiting the poor writer to the sort of chemical rocket that can he designed today.

You say that the ray generator would be sensitive, “since we have to assume tubes of some kind.” Do we, now? Let’s try a spot of assuming, and see what sort of power plant and ray projector we can dream up, even without going too far beyond our present scientific knowledge.

Power plant first. Suppose we make it an atomic energy set-up, using the fission of uranium 235 under neutron bombardment. We’ll need a source of neutrons to start off that reaction. Cyclotron, perhaps, since you seem to like a heavy power plant; though I think that with U-235 a simple, light, insensitive radioactive source might work as well. A cyclotron would have tubes to go out during an engagement, all right, but we needn’t worry about that; we’ll just use it to touch off the process at the start, and keep steam up afterward, since the reaction is self-perpetuating. Probably need a direct hit now to put that job out of action.

Ray projector? Well, I suppose we could turn the released energy into electricity, to be later transformed into some deadly radiation In a delicate ray generator. It seems to me that a stream of those 200-million-volt atomic nuclei given off by disintegrating uranium, and released in the general direction of the enemy through refractory projectors would be just as deadly and a lot simpler. That question of refractories Is a delicate one, I admit; but we’ll need them, anyway, for the power plant, so let’s not strain at gnats while swallowing camels.

Do I hear an objection from Mr. Ley? “If there is an insulating material that holds out against the energies released at the giving end, it is hard to understand why the same insulator should not be usable to safeguard the bull of the ship that is being rayed.”

Same answer as to the question : Why not armor-plate the ship against solid and explosive projectiles from Mr. Ley’s heavy artillery? Too heavy; and, perhaps, a whole lot more expensive than even the best nickel-steel armor. But if you insist, I’ll make my ship invulnerable to ray attack; only you’ve got to reciprocate, and turn yours into a flying fort, complete with 30-inch plate all round.

This begins to look like stalemate. So let’s compromise; fit out our warships of space with both rays and guns, ray screens, insulation, and armor-plate, and see what new forms of deviltry the boys can think up with that equipment.

It should be interesting. – A. Arthur Smith, 131 Aqueduct Street, Welland, Ontario, Canada.

Astounding Science Fiction

December, 1939 (p. 108)

To the defense of rays.

Dear Sir:

As a rule, your stories are good and your articles better; the article entitled “Space War,” by Wily Ley, is however, the exception that proves the rule.

Before I attempt to back up the above statement, perhaps I had better give my qualifications. I have some sixty-odd hours of college chemistry, twenty-two hours of college physics, and thirty-four hours of college math. I spent three years in the National Guard attached to a battery of 155 mm guns.

I am too lazy to attempt to check Herr Ley on his statements of armor weight, gun weight, et cetera, but they seem reasonable, so I will allow them to stand without argument – they would probably stand, anyway.

Taking up Herr Ley’s arguments in order, I wonder if it ever occurred to him that it would require quite a good power plant to lift a “fair-sized spaceship, about ninety yards long and twenty yards in diameter,” from the surface of the earth and then set it gently down again? It seems to me that the weight of the mechanism required to divert part of this power from drive to ray generator would not be prohibitive. Vacuum-tubes are delicate, but could be made stronger if necessary, and, if not, I believe would rather risk having a tube blow during the course of a battle and leave me without effective weapons than to have an enemy shell land in the ship’s magazine.

He kindly granted the possibility of dangerous rays and then stated that he did not believe they could be developed in the near future. Micro-waves – radio – from 30 cm. down in wave length would be quite disconcerting if there were some 50,000 watts being fed into them. You see, they are picked up by a metallic conductor as heat. They may not be what the science-fiction author has in mind when he refers to heat rays, but they’ll work quite nicely, I believe, and they focus into the neatest tight beam. As for ray shields, there is always heterodyning.

As to the impossibility of “holding a ray on a fast-moving distant target, that might be practically invisible with black paint against the background of black space,” just how many men could hit a black disk twenty yards in diameter on a dark night such a range and moving with such a velocity that a searchlight – just another ray – could not hold it?

In space a heat ray is an accumulative affair in that heat is dissipated only by radiation, which is a notoriously slow process at ordinary – 0-200 C-temperatures. This would mean that the heat ray would not have to be held on the target.

As for the disadvantages of guns, Herr Ley has neglected to mention that in warfare on earth, when a heavy gun is firing at a target the gun is relatively motionless with respect to the target. This simplifies aiming considerably. Dog fights between planes are never long-range affairs because of their relative velocities. Going back to ground fighting, however, a miss of twenty yards or so is as good as a hit because of the bursting range of the shell. A miss of one cm. in space is as good as if the shell had not been fired.

When Herr Ley advocates the use of 75s in space, it is obvious that he has never been around them when they were fired. I have, and I wouldn’t care to be in a closed room – even if it were evacuated – with one firing several rounds to the minute.

During the World War gas was used frequently so as to force the men to don gas masks. The masks cut down the firing efficiency noticeably. I wonder when effect a space suit would have on accuracy?

The science of exterior and interior ballistics is built around the presence of air and a fairly strong gravitational field. It would take some time to develop a science of vacuum ballistics.

Reading this over it appears that I have laid the foundations – or destroyed them – for a good way – right here on earth between Herr Ley and me. I’ll try to prepare myself for his counter-attack, because I don’t believe I destroyed him entirely. – J.M. Cripps, Manhattan, Kansas

Astounding Science Fiction

May, 1940 (pp. 159-161)

Yes, but who’s going to use a slow spaceship if the enemy has fast ones?

Dear Mr. Campbell:

It seems now that the latest vogue in science-fiction stories is that of rocket-racing, and it is only natural that you should secure the best of that type yet published. By this, I refer to the clever and well-written “Habit” by Lester del Rey in the November issue. This excellent little piece has that “certain something” that sets it off as a typically Astounding story. I honestly believe that were I given an armful of untitled, anonymous, and as yet unpublished manuscripts, I could tell within ninety percent or better which would find refuge in Astounding and which would go to your umpteen competitors. It’s style, not plot, that makes Astounding the “class magazine” that it is.

May I add a line or two to the rumpus stirred up over the merits of the “General Swamp” serial. To my mind it ranks with the best of any two-part serial yet published. Its handling was so uniquely different that it captivated me from the very start. It was realistic to the point of having me half believe I was reading actual reports and military accounts! Kick on the hard-to-pronounce names? Not me! surrounded as I am by left-over handles of the Indian period – Skowhegan, Messalonskee, Norridgewock, Kennebec, Mooselookmeguntick, Cobbseecontee, et cetera. How does Arkgonactl and Golubhammon compare with these?

Space war articles and letters by Ley and Jameson appeal greatly to me, despite the fact that they hopelessly destroy – and quite logically, too – my pet dreams of flashing ray battles In the void. But wouldn’t two ships traveling a parallel course at equal or near equal speeds be visible lo one another? Jameson seems to think not. Also comes up again the slow-speed spaceship theory that blasts the seven-mile-per-second principle – page 70 of “Space War Tactics” – off the records. Still, Jameson accepts that, too, … – James S. Avery, 50 Middle Street, Skowhegan, Maine.

SCIENCE DISCUSSIONS

Experts transposed?

Dear. Mr. Campbell:

That the problems of spate war and space war tattles are infested with wide gaps of knowledge and with difficulties of all kinds is proven by one fact: I recommend guns, while an old gunnery expert like Malcolm Jameson prefers rocket torpedoes! If it were the other way round, nobody would be surprised.

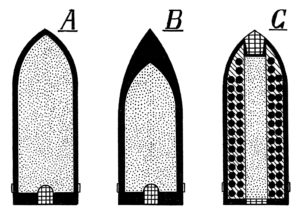

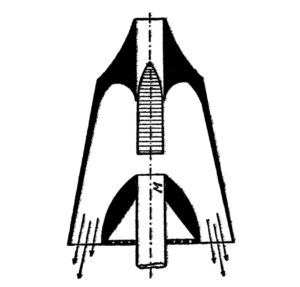

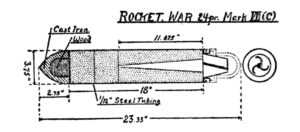

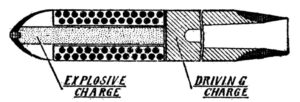

My reasons for recommending guns were already stated in my article “Space War,” the principal one being that guns with ammunition are lighter and less bulky than rocket torpedoes, provided that an appreciable number of rounds is to be carried. And since my comparison was based on rocket’ torpedoes capable of attaining the same velocity as gun projectiles, I think that the argument is still valid, if the torpedoes were to attain higher speeds they would he still heavier and still bulkier.

Answering first to Mr. Jameson’s letter I hasten to assert that I do not think that the weight of large caliber guns could he reduced very much, unless by the use of new alloys. I was speaking of small guns, 75 millimeter and less, and I still hold that I am right. The new anti-tank guns in all armies prove that point; they are much lighter than anything built so far. (I may add that those of the Swiss army are also equipped with a recoil eliminator.) And that they are effective enough has meantime been demonstrated by the new 37-millimeter anti-tank guns of the U.S. army that “disintegrated” 1 ½-inch steel armor plate at a thousand yards without a moment’s hesitation. That 1,000 yard range means, of course, in air – for space conditions it might safely be multiplied by a hundred or even more.

As far as tactics of combat are concerned, I, having neither experience nor theoretical training, have to be quiet. I cannot help but feel, however, that the tactics of sea or aerial combat do not apply to a very great extent. We always have to hear in mind that an orbit in space and a course in air or on the high seas are not exactly the same. Spaceships are not steamers that travel at will, but rather canoes in swift and powerful currents. These canoes have paddled that permit some movement at will and some steering, and If the “currents” were not as regular and ad calculable as they are the case would be hopeless.

Spaceships, therefore, will either pass each other in opposite directions and at such relative speeds that hardly anything could be done, or else they will follow about the same course and by necessity have about the same velocity. It is the latter condition I had in mind, and it is in that condition where guns will he advantageous. Mine laying is, of course, a nice idea, but again I do not quite see why mines should be superior to guns, generally speaking. Mr. Jameson is trying to do something that is very hard to do when he proposes that the space mines, or iron pellets, should be “shot out of mine-laying tubes clustered about the main drive jets. They would be shot out at right angles – and given a velocity exactly equal to the ship’s speed, so that they would hang motionless where they were dropped. The latter does not hold true exactly; the pellets would at once start moving in the general direction of the Sun – If they are exactly motionless it would be the exact direction toward the Sun – but since that movement would he very slow at first and the enemy ship reaches the area of the mine field In a few seconds, that factor can he disregarded. What bothers me is the problem how the mines could be shot out with a velocity exactly equal to the ship’s speed. That speed is assumed to be about 20 – 25 miles per second. Muzzle velocities of guns will be between one and – possibly – one and a half miles per second. And even the gas molecules in the rocket exhaust do not travel faster than, say, three miles per second. If a method could be found to shoot the space mines away from the ship with 20-25 miles per second, that method should be applied to throw shells.

Since I have started criticizing other people’s Ideas, I might as well say a few words about Robert Heinlein’s enjoyable story “Misfit.” Generally speaking, I think that moving an asteroid for the purpose of using it as a station in space is a very wasteful business. It would take much less fuel to transport building material to the chosen spot in space from Earth or Mars. An asteroid possesses an awful amount of useless mass that has to be transported, and each pound of mass requires so and so much fuel. It Is somewhat like moving a large mountain from one continent to another because there is a forest growing on top of the mountain and the larger trees of that forest are to be used to build a raft.

But even if we concede lo the waste of fuel to move the asteroid, there Is no reason to waste more than half of that fuel in giving “88” “a series of gentle pats, always on the side farthest from the Sun.” What has to be accomplished is to slow down the orbital velocity of the asteroid so that the gravitational attraction of the Sun gets the upper hand and draws it closer. Which is done most effectively in setting off the rocket charges in such a way that they point “ahead,” at right angles to the line drawn from the asteroid to the Sun. The resulting movement would be along an elliptical curve – somewhat distorted, to be sure – but not a hyperbolic curve. And there is no need for such unnecessary accuracy. If the asteroid should finally possess a few hundred feet of orbital velocity more or less, is really unimportant. It would make a difference of ten or twenty miles – or even fifty or a hundred – in the average distance from the Sun. There is no reason why that should matter, just as it does not matter whether an island in the Atlantic Ocean is half a mile farther west or not; it only matters that captains know where It is. Besides, the orbit of the asteroid could be corrected at any time, if desired. But I wouldn’t move asteroids at all.

I wish to say “thank you” to Mr. E. Franklin of Jamaica Plain for his nice and interesting letter in the October issue. The real trouble with articles is that they have to be shorter than the “Gray Lensman.” – Willey Ley, 35-33 20th St., Long Island City, N.Y.