“Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.” –

– “The more things change, the more they stay the same.”

Akin to my earlier post about discovering photographs of the ditching of Julius Brownstein’s F4F Wildcat, the following article – from 1947 – was also found by chance: While randomly perusing – on 35mm microfilm – issues of The New Republic from the 1940s.

Written almost seventy years ago, the article by Thomas Whiteside – covering the introduction and effect of what were then “new”, if not revolutionary, technological changes – FM radio, advances in typesetting and television broadcasting, and even a remarkable intimation of fax and email – upon long-existing methods for the production, communication, and distribution of information, is as relevant today as when it appeared in December of 1947.

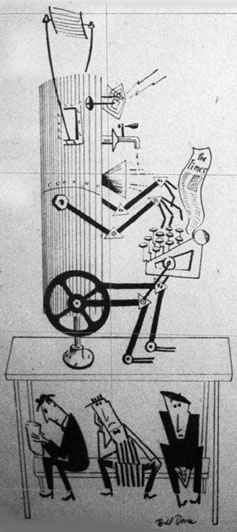

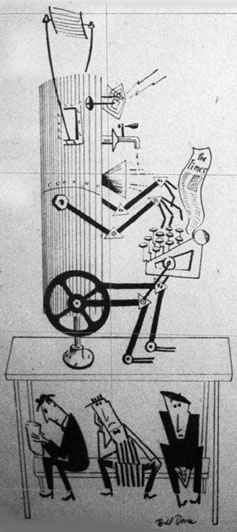

The article is transcribed verbatim, and appears below, including reproductions of two cartoons in the original item. One depicts a farmer leisurely riding a tractor, on which is mounted a video monitor via which he can view live entertainment – 1947 style wifi? The other is an allegory on technological displacement, showing a fully autonomous linotype machine (1947 style AI?) perched atop a forlorn trio of businessman / typesetter / beret-wearing, black-clad, bongo-less “beatnik” musician.

Though he provides a very clear; very lucid account of the technological nature and effects – potential, and very real – of advances in information technology, Whiteside only devotes his three final paragraphs to possible solutions for the “human” effects of this technology on those whose lives were long-dependent on the creation, production, and distribution of text and music: Technological and vocational obsolescence; collaboration between government and the private sector, in a search for solutions to the effects of such changes; retraining.

Perhaps this brevity should be respected, for the solutions to such issues were, and perhaps have always been, far more easily addressed in words and proposals; plans and ideas, than concrete solutions.

There was something quaint and fascinating about this article on first reading. Then, something more was apparent, eerily and movingly relevant to its “core” idea: How can man (“man” as an individual; “man” as a community or nation; “man” as an abstract concept) adjust to and keep pace with the inevitability of technological change, in a world where he very much defines himself by his dependence on, use of, and adaptation to that technology?

The fundamental and underlying topic of this article – What is to become of people? – is as relevant now, in 2017, as it was some seven decades ago. (Well, it has always been relevant.)

If not more.

For if technological change is a given, two other aspects of that “change – possibly unforeseen in 1947 – are the accelerating pace of that change, and, the realization that technological change can be generated and perpetuated by that technology itself, in the form of artificial intelligence. Though it as impossible as it is naive to draw a “straight line” – a historically straight, deterministic, line of inevitability, that is – from the present to the future, or, let alone congruently “map” the present onto the events of the past, it would seem that our world has been undergoing a revolution – a cognitive and social revolution, at least – that has the potential to be as wrenching, in its own quiet way, as was the “first” industrial revolution.

Perhaps it is well that we do not know the outcome – if there is to be an outcome.

And so; and then; on second reading, I was reminded of notable articles and essays, and some academic papers about this topic, that have appeared in the past few years. The authors and titles of these items (44 items by 38 authors, all with links) are listed following Whiteside’s article. You may heartily agree with some of these items, vehemently disagree with others, and ponder more than a few. (On occasion, one can find gem-like insights – here and there – in the talk-back strings to some of these writings.)

Regardless, they’re all provocative.

Communications Revolution

Thomas Whiteside

The New Republic

December 15, 1947

Petrillo’s record ban and the Typographer’s strike fit into the pattern of an industry facing job-shaking changes.

FOR A NICKEL, the American juke-box not only plays music, but also glows, bubbles and changes color. At the present time, the crowned heads of the jukebox industry are undergoing not dissimilar facial transformations. The cause of their chafer is the decision of James C. Petrillo’s American Federation of Musicians (AFL) to stop making recordings after December 31, when Petrillo’s present contracts with the recording companies expire. Without new records, the country’s 600,000 jukeboxes gradually will be silenced – a severe blow not only to the high schools of America but to me whole complex jukebox economy, from Wurlitzer Hall to Joe’s Diner.

But important though it be, the dislocation of this jumping $500 million business is symptomatic of a technological crisis now spreading through the entire communications industry, from music and radio to photoengraving and typesetting. For the public, the revolutionary new techniques will open an era in which, for instance, newspapers will be circulated by radio and in which common mail may be carried electronically by a special television process. But for the 500,000 people now employed in the mass-communications industry, these same techniques will mean widespread unemployment and the need to turn to entirely new skills.

Perhaps the most widely heralded indication of this looming crisis, and one which will be used here as the first of several examples, has been the dire predicament of James C. Petrillo.

In the current American language, the very word Petrillo has become so enriched with connotations as to be used to frighten small children. Petrillo himself is comparatively oblivious to the catalogue of abuse which has been compiled by the press to describe his motivations. He sees only one problem, overwhelming and immediate: the job protection of his 225,000 union members. He sees no reason why he should encourage the development of a system whereby a musician is replaced by a lump of wax.

This stern philosophy has previously led him to prohibit – in the absence of what he considered proper pay – the services of his musicians over two efficient and rapidly expanding media of communication, FM and television. His decision to ban the making of new recordings by members of his union will cost him dearly. In the first place, his 6,000 recording artists stand to lose $5 million annually in wages. Second, Petrillo’s union will lose a considerable part of record royalties previously paid into his $2 million annual welfare fund. (The latter loss, however, is directly due to the Taft-Hartley Act, which prohibits employer contributions to union welfare funds except under conditions unacceptable to most self-respecting unions.) Petrillo’s long-range risk is more serious, for the sale of records in America has had much to do with the growing American appetite for music, good and otherwise.

Such over-all considerations, however, have little effect on Petrillo, or many another union leader in a similar spot. Petrillo intends to maintain full, profitable employment for what he fondly calls “my boys,” even if the process involves a fight against new technology. Under present conditions, there are simply too many musicians for available jobs. Petrillo himself recently predicted that unless a halt were called on recordings, the phonograph needle would gouge many thousands of musicians out of the industry within a few months.

But the ups and downs of the man with the fiddle in the worn black case affect a whole industrial complex which he can hardly oversee. In point of fact, Petrillo’s decision to stop recordings may save the jobs of many musicians, but it will also probably affect the livelihood of some thousands of people in the recording and related companies, many of them war-born. A shortage of recordings could cut into the radio-phonograph industry, the 12,000 record shops now existing in the country and, to some extent, the plastics industry.

Petrillo and FM.

In view of Petrillo’s insistence on “live” performances by his musicians, his recent decision to prohibit the duplication of network programs on FM stations is looked on by many FM broadcasters as a technique of cutting off his nose to spite his face. The more forward-looking of the FM broadcasters, who realize that they have a medium ideally suited for operation by the small businessman, argue that if Petrillo helped FM, he would also help break up the quasi-monopoly now enjoyed by the major conventional radio networks. They point out that the development of FM – there are currently about 350 FM stations on the air – will also mean the employment of more musicians.

At present, the structure of AM, or conventional radio, with its imperial system of high-powered, unobstructed, clear-channel stations, makes the creation of further national AM networks, and thus the employment of additional staffs, a virtual impossibility. The introduction of FM, the wonder medium of staticless, high-fidelity radio transmission, opens the door for the building of as many as 3,000 new radio stations in the country, and possibly 20 new networks employing some 50,000 people. More important, it gives the listener new opportunities to hear kinds of programs seldom broadcast by the conventional networks.

At present, the structure of AM, or conventional radio, with its imperial system of high-powered, unobstructed, clear-channel stations, makes the creation of further national AM networks, and thus the employment of additional staffs, a virtual impossibility. The introduction of FM, the wonder medium of staticless, high-fidelity radio transmission, opens the door for the building of as many as 3,000 new radio stations in the country, and possibly 20 new networks employing some 50,000 people. More important, it gives the listener new opportunities to hear kinds of programs seldom broadcast by the conventional networks.

The opportunity for employment of many hundreds by promoting classical music over FM is a good example. The grand vizier of conventional radio, Hooper, to whom all account executives bow low, so far has given the big networks a discouraging report on classical music. Beethoven’s Hooper is not generally high enough to warrant serious consideration by such determinants of popular culture as the makers of Ex-Lax, Kix or Serutan, even were his name to be spelled backwards. Numerically, however, the audience for good music is large. Within two or three years it would be economically quite feasible for an enterprising group to establish an FM network specializing in classical-music broadcasts.

FM broadcasters point out that there are many other minority interests which can be reached, to the profit of public and musicians alike, by the new medium. But the entire development of FM is now being retarded by the fight between Petrillo and the networks. Apparently Petrillo feels that too many FM frequencies have been grabbed up by conventional radio interests and that to allow his musicians to broadcast over FM would in effect strengthen the power of his network enemies. Unfortunately, the FM groups to suffer will not be the wealthy entrenched interests but the groups of veterans who have ventured into FM with high hopes and slim purses. According to the Frequency Modulation Association, 95 percent of all FM stations are losing money. Well established AM stations can afford to operate their FM outlets at a loss. The small, independent operators, on the other hand, who find themselves completely at the mercy of “the natural flow of economic forces,” are bitter at what they consider Petrillo’s shortsightedness in failing to consider their problems and, in the long haul, his own.

Old versus new.

But the Petrillo affair is only the beginning of the kind of strife into which the entire communications industry is likely to be forced as a technological revolution sweeps in. Every industry in America, of course, faces dislocations of employment and of skills as new labor-saving machinery is invented and produced. But the communications industry has a status and importance peculiarly its own in that it carries or produces not mere goods but the words and symbols on which a democratic people heavily relies for its social and political decisions.

If an iceman discourages trade in refrigerators, the housewife along his route will suffer, at worst, inconvenience. But if a printers’ union blocks a new system of printing without linotype machines, it may deprive hundreds of small towns of a cheap, efficient and hitherto unavailable news service.

If an iceman discourages trade in refrigerators, the housewife along his route will suffer, at worst, inconvenience. But if a printers’ union blocks a new system of printing without linotype machines, it may deprive hundreds of small towns of a cheap, efficient and hitherto unavailable news service.

Almost every facet of the communications industry is facing just this kind of problem. An inkling of developments around the corner came to the public eve in the recent strike of the Chicago Typographical Union against six Chicago newspapers over conditions of employment. A few years ago a similar strike would have completely crippled the newspapers. Actually, as the strike progressed, newspaper circulation in Chicago was scarcely affected. The newspapers called in batteries of office girls who typed out the news columns on ordinary paper. The typed sheets were pasted together and photo-engraved without need of linotype operators.

A similar system has been employed for several months by John. H. Perry (see the NR, November 17) to produce some of the newspapers in his Florida chain. Perry by-passes the linotyping and stereotyping processes by photo-engraving and the use of self-justifying typewriters which space out an even, full line. Perry also uses girl typists rather than linotype operators. The finished photo-engraved newspaper differs little in appearance from the standard product. There is not the slightest doubt that the extension of this new, cheap and efficient printing system would cause widespread unemployment among linotype operators.

Teletype and facsimile.

The lino-typists face considerable trouble, too, in the introduction of the teletypesetting machine, which automatically sets type by remote control from a master machine many miles away. In a newspaper chain, for example, every tele-typesetting machine installed will tend to replace a linotype operator. Another threat to the typographical unions comes from the rapid development of facsimile reproduction, familiar to all newspaper readers in the form of wirephotos. The potential achievements of facsimile were dramatically shown in the spring of 1945, when the New York Times facsimiled special editions by wire to the West Coast during the San Francisco Conference. Again the basic process was photoengraving. The typographical unions are expected to fight hard against the spreading of the facsimile system.

As a hedge against unemployment, the International Typographical Union recently appropriated a rumored $300,000 to found and operate its own newspapers, thereby providing work for linotype operators displaced by new processes. Meanwhile, it evidently intends to right development of the facsimile system. Many employers are jittery about using facsimile for fear of offending the powerful printing unions.

An example of this nervousness can be seen in the printing of stock-market reports in three Eastern newspapers. Normally, these stock-market reports arrive in the form of tape, which has to be retyped by girls before being sent to the composing room. This retyping process involves incredibly tedious work and a high percentage of error. To reduce errors, an organization specializing in facsimile suggested that the original texts be facsimiled into the newspaper office by coaxial cable. The facsimile text, it proposed, could then be photo-engraved for insertion in the newspaper without passing through the intermediary stages of copying and linotyping. The companies involved refused even to consider the possibility on the grounds of possible hostility from the unions.

Understandable though the union position is in a situation like this, the fact remains that retarding the development of facsimile will also retard new kinds of employment. Wired facsimile, for instance, is likely to be followed by radio-borne facsimile. Then the owner of a facsimile set could receive printed spot news and features in his own home merely by tuning in to his local radio station. Commercial facsimile is already due to start by the beginning of the year, when 15 of the country’s leading papers will begin transmitting newspapers by radio. Within a few fears, the number of participating stations may run into the hundreds, with appropriate increase in demand for news staffs and skilled groups to handle the self-justifying typewriters on which facsimile news copy will be set.

Television boom.

An even greater promise of new employment is offered by television, now entering a boom period. One television official estimates that within five years the television industry will provide jobs for 300,000 people. Assuming a total use of five million television sets in that period, he estimates that television maintenance, installation and service would bring work to some 85,000 – or three times the number of radio service workers employed today, white at the end of the first full television year the dollar volume of replacement parts would reach fin annual figure of $220 million.”

Another television executive predicted that television will be doing a business involving $6 billion in capital investments, or more than double the total capital invested today in the motion-picture industry. Whether or not these estimates are over-optimistic, they give a good indication of extremely rapid television expansion. Television officials expect immediate demand for new skills. There are very firm indications, for example, that the wire services, such as the Associated Press and the United Press, will barge into the field of television news coverage. The AP already has begun a television newsreel service for broadcast over Baltimore, Philadelphia and New York television stations. There are also indications that major papers will take steps to begin their own newspaper television networks.

Video networks.

Opening of microwave relay stations between New York and Boston to carry television programs marks the start of a nationwide microwave network. Such a network will throw wide the radio spectrum to almost every conceivable type of communication. The invention of a new technique of broadcasting, known as Pulse-Time Modulation, will allow dozens of programs to he carried on the same radio frequency simultaneously. It will mean that perhaps within 15 years an Iowa farmer may tune in his radio to choose not one, but any of 20 AM, FM or television programs relayed simultaneously over his local radio station. Yet within the same period, Pulse-Time Modulation may also reduce almost to obsolescence the standard land-line telephone system used today, and thus dislocate thousands of conventional telephone workers.

The development of another new device for radio transmission, known as Ultrafax and combining the principles of television and motion-picture photography, brings possibilities for the transmission of written material at the extraordinary rate of a million words a minute. Should Ultrafax live up to its potentialities as shown in laboratory tests, it could revolutionize the whole post-office system by making possible a vast electronic V-mail Service.

Promise and threat.

Such is the promise – and to unions, the threat – of new means of mass communication in the coming era. The transition will be hard, perhaps chaotic. Realization of the revolutionary nature of the devices involved is causing a good deal of speculation by labor specialists in the industry as to the manner in which orderly progress into the new technological age will be made. Some of them feel that it is time for the formation of an over-all commission composed of every segment of the communications industry and of government.

Such a commission, they believe, should provide the facilities to teach workers thrown out of jobs by one machine to use another, to provider proper unemployment relief for those no longer employable and to steer young workers into the most rapidly, expanding fields of employment within the industry.

“A man is apt to get pretty mad when he sees a mechanical man moving in alongside him in a shop,” remarked a communications unionist. “If government and industry can sit down with us and look at the problem as a long-range one, then particularize and help us straighten this thing out in an orderly way, the workers, the industry and the public are going to be a lot better off, and a lot sooner.”

____________________

Man, Technology and the Future

Andreessen, Marc – Why Software Is Eating the World (August 20, 2011)

Appleyard, Brian – Why futurologists are always wrong (April 10, 2014)

Berlinski, Claire – Globalization and the Elite Chasm (December 23, 2015)

Bourdieu, Pierre and Wacquant, Loïc Wacquant – The New Global Vulgate

Carr, Nicholas – All Can Be Lost (November, 2013)

Carr, Nicholas – The Eunuchs Children (May 25, 2014)

Carr, Nicholas – The singularity is always near (December 22, 2014)

Courrielche, Patrick – Stream Ripping How Google YouTube Is Slowly Killing the Music Industry (August 3, 2016)

Drum, Kevin – Welcome, Robot Overlords. Please Don’t Fire Us? (May / June, 2013)

Dunn, Gaby – Get rich or die vlogging: The sad economics of internet fame (December 14, 2015)

Elliott, Stuart W – Anticipating a Luddite Revival (Spring, 2014)

Friend, Tad – Sam Altman’s Manifest Destiny – (October 10, 2016)

Graeber, David – Of Flying Cars and the Declining Rate of Profit

Handley, George – Wealth Poverty and Ignorance (Jul 25, 2013)

Johnson, David V – Do Friedmans Dream of Electric Sheeple? (December 13, 2016)

Kotkin, Joel – Are We Heading for An Economic Civil War? (November, 8, 2015)

Kotkin, Joel – Tech Titans Want to be Masters of All Media We Survey (November 22, 2015)

Kotkin, Koel – The New Masters of the Universe (December 21, 2015)

Lanier, Jaron – The Internet Destroyed the Middle Class (May 12, 2013)

Lehman, Chris – Having Their Cake and Eating Ours Too

Leonard, Andrew – The Internet’s destroying work — and turning the old middle class into the new proletariat (July 12, 2013)

Lepore, Jill – The Disruption Machine (June 23, 2014)

McCurry, Justin – Japanese Company Replaces Office Workers with Artificial Intelligence (January, 5, 2017)

Mims, Christopher – Technology Versus the Middle Class (January 22, 2017)

Mokyr, Joel – The Next Age of Invention (Winter, 2014)

Morozov, Evgeny – The Taming of Tech Criticism

Nelson, Robert H – The Secular Religions of Progress (Summer, 2013)

Packer, George – Change the World (May 27, 2013)

Pein, Corey – Cyborg Soothsayers of the High-Tech Hogwash Emporia

Pein, Corey – Mouthbreathing Machiavellis Dream of a Silicon Reich (May 19, 2014)

Peterson-Withorn, Chase – Billionaire Jeff Greene Says Technology Will Kill White-Collar Jobs, Hosts Conference On Inequality (December 7, 2015)

Pethokoukis, James – Is the internet killing middle class jobs (April 2, 2015)

Pournelle, Jerry

The Centre Cannot Hold (April 25, 2014)

The Future of Work, Continued (1) (April 26, 2014)

The Future of Work, Continued (2) (April 28, 2014)

Rampell, Catherine – It Takes a B.A. to Find a Job as a File Clerk (February 19, 2013)

Rothfeder, Jeffrey – The great unraveling of globalization (April 24, 2015)

Rotman, David – How Technology Is Destroying Jobs (June 12, 2013)

Rushkoff, Douglas – How Technology Killed the Future (January 15, 2014)

Salzman, Hal – What Shortages? – The Real Evidence About the STEM Workforce (Summer, 2013)

Staw, Barry M – Why No On Really Wants Creativity (1996)

Storey, Benjamin – Tocqueville on Technology (March 24, 2014)

Thompson, Derek – A World Without Work (July, 2015)

Yudkowsky, Eliezer – The Robots, AI, and Unemployment Anti-FAQ (July 25, 2013)

At present, the structure of AM, or conventional radio, with its imperial system of high-powered, unobstructed, clear-channel stations, makes the creation of further national AM networks, and thus the employment of additional staffs, a virtual impossibility. The introduction of FM, the wonder medium of staticless, high-fidelity radio transmission, opens the door for the building of as many as 3,000 new radio stations in the country, and possibly 20 new networks employing some 50,000 people. More important, it gives the listener new opportunities to hear kinds of programs seldom broadcast by the conventional networks.

At present, the structure of AM, or conventional radio, with its imperial system of high-powered, unobstructed, clear-channel stations, makes the creation of further national AM networks, and thus the employment of additional staffs, a virtual impossibility. The introduction of FM, the wonder medium of staticless, high-fidelity radio transmission, opens the door for the building of as many as 3,000 new radio stations in the country, and possibly 20 new networks employing some 50,000 people. More important, it gives the listener new opportunities to hear kinds of programs seldom broadcast by the conventional networks. If an iceman discourages trade in refrigerators, the housewife along his route will suffer, at worst, inconvenience. But if a printers’ union blocks a new system of printing without linotype machines, it may deprive hundreds of small towns of a cheap, efficient and hitherto unavailable news service.

If an iceman discourages trade in refrigerators, the housewife along his route will suffer, at worst, inconvenience. But if a printers’ union blocks a new system of printing without linotype machines, it may deprive hundreds of small towns of a cheap, efficient and hitherto unavailable news service.