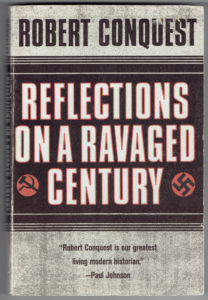

Reflections On A Ravaged Century

Robert Conquest

W.W. Norton & Company

2000

There are men who are revolutionaries by temperament, to whom in fact bloodshed is natural.

***

There is no formula that can give infallible answers to political, social, economic, ecological and other human problems.

***

As Lionel Trilling once wrote: “This is the great vice of academicism, that it is concerned with ideas rather than with thinking…”

***

Both Nazis and Marxists themselves often proclaimed their affinity with the millenarian demagogues of the period of the German Peasant War, claiming that these were men born centuries before their time, but as [Norman] Cohn says [The Pursuit of the Millenium, New York, Oxford University Press, 1970], “it is perfectly possible to draw the opposite moral – that, for all their exploitation of the most modern technology, Communism and Nazism have been inspired by phantasies which are downright archaic.”

As with the chiliastic movements of centuries long past, modern revolutionaries have, as Cohn points out, claimed to be charged with the unique mission of bringing history to its preordained consummation.

***

For the capacity to envisage the alien is not distributed according to any of our usual intelligence tests. People can be able, clever, but not in the deepest sense wise. Examples of a run-of-the-mill academic or bureaucratic or even political “brilliance” are not seldom regarded as adequate in the responsible offices of the West, with disastrous results.

Shakespeare, in fact, was a better guide to the modern world than – in particular – certain circles with an inordinately powerful influence on the West, for he even produces characters, like Cassio, who typify the inability of inexperienced minds to understand the Iagos of the real world.

Dostoevsky writes of a human type, “whom any strong idea strikes all of a sudden and annihilates his will, sometimes forever.” The true Idea addict is usually something roughly describable as an “intellectual”. (8)

Times of stress have produced both revolutionaries and mystics, Zealots and Christians. It would be hard to define precisely the psychological differences between the types. And indeed, there is usually a good deal of movement from one view to the other; even in the United States, one notes some of the political activists of the sixties later becoming involved in strange religious quietisms. Such changes are explicable psychologically, but hardly sociologically.

For a useful, almost classical demonstration of the revolutionary mind-warp, the motivation behind acceptance of a totalitarian Idea, we turn to an interview given by the Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm on “The Late Show,” 24 October 1994 (see TLS, 28 October 1994). When Michael Ignatieff asked him to justify his long membership of the Communist Party, he replied: “You didn’t have the option. You see, either there was going to be a future or there wasn’t going to be a future and this was the only thing that offered an acceptable future.”

Ignatieff then asked: “In 1934, millions of people are dying in the Soviet experiment. If you had known that, would it have made a difference to you at that time? To your commitment? To being a Communist?”

Hobsbawm answered: “This is a sort of academic question to which an answer is simply not possible. Erm … I don’t actually know that it has any bearing on the history that I have written. If I were to give you a retrospective answer which is not the answer of a historian, I would have said, ‘Probably not.’“

Ignatieff asked: “Why?”

Hobsbawm explained: “Because in a period in which, as you might say, mass murder and mass suffering are absolutely universal, the chance of a new world being born in great suffering would still have been worth 1 backing. Now the point is, looking back as an historian, I would say that the sacrifices made by the Russian people were probably only marginally worthwhile. The sacrifices were enormous, they were excessive by almost any standard and excessively great. But I’m looking back at it now and I’m saying that because it turns out that the Soviet Union was not the beginning of the world revolution. Had it been, I’m not sure.”

Ignatieff then said: “What that comes down to is saying that had the radiant tomorrow actually been created, the loss of fifteen, twenty million people might have been justified?”

Hobsbawm immediately said: “Yes.”

It will be seen that, first, Hobsbawm accepted the Soviet project not merely on the emotional ground of “hope” but on the transcendental one of its being the “only” hope. Then, that he was justified because, although it turned out wrong, it might have turned out right (and it was not only a matter of deaths, but also of mass torture, falsification, slave labor). Finally, that he believes this style of chiliastic, absolutist approach to reality is valid in principle.

It might be added that addiction to a historico-social analysis which admittedly proved defective could be taken to cast some doubt on the method, and hence the conclusions, of Hobsbawm’s historical work – some of which, on the Bolsheviks, we shall consider in its context in a Inter chapter. (10-11)

There is no formula that can give infallible answers to political, social, economic, ecological and other human problems. (15)

The Culture of Sanity

Each country is inhabited not only by its citizens but also by ghosts from the past and by phantasms from imaginary futures or saints from lands outside time. (29)

The great political philosopher Michael Oakeshott notes that for some people government is “an instrument of passion; the art of politics is to inflame and direct desire.” (30)

The Nation: Hope and Hysteria (Nationality, Nationalism, Fascism, National Socialism)

But identification with the masses was in all these cases more than a mental generalization. It also, obviously, involved a psychological mechanism – of the sort Kierkegaard refers to when he writes that

people flock together, in order to feel themselves stimulated, enflamed and ausser sich. The scenes on the Blocksberg are the exact counterparts of this demoniacal pleasure, where the pleasure consists in losing oneself in order to be volatilised into a higher potency, where being outside oneself one hardly knows what one is doing or saying, or who or what is speaking through one, while the blood courses faster, the eyes turn bright and staring, the passions and lusts seething.

Everywhere we come across the ease with which people passed from Communism to what were in theory its most virulent enemies – Fascism and National Socialism. Several Italian Fascist leaders, like Bombacci, had held positions in the Comintern – as had Jacques Doriot in France, who even led a French pro-Nazi military formation on the Eastern Front in World War II.

Hitler himself said that Communists far more easily became Nazis than Social Democrats did. On another occasion he remarked, “the Reds we had beaten up became our best supporters,” a point also noted by others. A remarkable firsthand example is given by Patrick Leigh Fermor in A Time of Gifts, his famous account of his walk across Europe as a penniless eighteen-year-old in 1934. In a German workmen’s bar late one night he made friends with a group of young factory hands just off a late shift. One of them offered to put him up in a family attic. There he found what seemed to be “a shrine of Hitlerism” – flags, photographs, posters, slogans, emblems. His new friend laughingly said he should have seen it last year – all “Lenin and Stalin and Workers of the World Unite.” He and his friends were Communists and used to beat up Nazis in street fights. Then, “suddenly,” he had realized that Hitler was right, and he and his friends were now SA men. “I tell you, I was astonished how easily they all changed sides,” he said. (64-65)

Till recently it was thought proper to pretend that all human beings are very much alike, but in fact anyone able to use his eyes knows that the average of human behavior differs enormously from country to country. Things that could happen in one country could not happen in another. (68)

Totalitarian Party – Totalitarian State

The Idea does not subsist on its own. It is not just a system of thought bombinating in a vacuum, or entering the intellectual atmosphere and being accepted as general guidance after reasonable discussion – though its proponents have sometimes presented it as such with a view to winning, or confusing, those concerned.

On the contrary, it requires interpreters. Every social and every human phenomenon has to be given correct evaluation. But this can only be done by a recognized authority.

In the sense we are speaking of, a doctrine or dogma becomes incarnate in a “party of a new type,” as Lenin calls the Bolsheviks – a party based (as were the National Socialists after them) on an organizational and doctrinal command system.

Its leadership, an authoritative center with power to interpret the Marxist runes, was essential to unity and purity of thought, and to correctness of tactics. (Thus, in the biological disputes of the mid-1940s, the Communist Central Committee was the final arbiter – and was recognized as such by Communist biologists when it ruled against them.)

Not that this phenomenon is “new” except compared to the looser party system then prevalent in Western Europe. It resembles those “sworn brotherhoods” or millenarian sects of an era that had long passed (in any serious way) in the advanced countries. Its immediate roots were in the conspiratorial groups of the nineteenth century. Western social democrats, and Westernizing progressives in general in Russia itself, regarded the conspiratorial organization of the Bolsheviks as an unfortunate but understandable product of the illegal and semi-legal struggle against Tsarism, which would surely be given up when political liberty prevailed. Many Bolsheviks thought the same.

The writings and actions of the revolutionary-messianic type in fact resemble each other down the centuries. And, of course, revolutionaries have admitted, or rather exalted, the resemblance. Norman Cohn remarks (in later editions of The Pursuit of the Millennium) that Communism and Nazism are inclined to be “baffling for the rest of us” because of the very features they have inherited from an earlier phase in our culture, now forgotten, but still appealing to more backward areas of the world. In such countries as Russia and China, the apocalyptic view was “appropriated and transformed by an intelligentsia which, alike in its social situation and in the crudity and narrowness of its thinking, strikingly recalls the prophetae of medieval Europe.”

Both Nazis and Marxists themselves often proclaimed their affinity with the millenarian demagogues of the period of the German Peasant War, claiming that these were men born centuries before their time, but as Cohn says, “it is perfectly possible to draw the opposite moral – that, for all their exploitation of the most modern technology, Communism and Nazism have been inspired by phantasies which are downright archaic.”

As with the chiliastic movements of centuries long past, modern revolutionaries have, as Cohn points out, claimed to be charged with the unique mission of bringing history to its preordained consummation. He notes of the earlier versions:

And what followed then was the formation of a group of a peculiar kind, a true prototype of a modern totalitarian party: a restlessly dynamic and utterly ruthless group which, obsessed by the apocalyptic phantasy and filled with the conviction of its own infallibility, set itself infinitely above the rest of humanity and recognised no claims save that of its own supposed mission.

The staff, and leading figures, of such movements were and are from a more or less educated stratum. When they gain the support of “the masses” or “the nation,” it is through such a network, expanded to bring in representatives of the larger and less educated sections. (74-75)

This century has been in fact the first in which the groups taking over countries had the power to use the state machinery to impose doctrinally produced errors on the whole of the society. (81)

Into the Soviet Morass

The autocratic traditions and habits, and the Utopian tradition that had arisen in reaction to it in the absence of any but the beginnings of civic experience, were the conditions of the Leninist revolution. And the new regime even, in a different sense, inherited the old imperialist expansionism which Engels had remarked on as something that would only end when Russia had “a constitutional forum under which party struggles may be fought without violent convulsions” – not applicable to Lenin’s regime, in which the tradition of Moscow as the Third Rome was replaced by the Third International.

Grossman, himself Jewish and the Soviet Union’s leading writer on Hitler’s Holocaust, draws the analogy with the Nazis and the Jews. A woman Communist activist explains, “What I said to myself at the time was ‘they are not human beings, they are kulaks.’… Who thought up this word ‘kulak’ anyway? Was it really a term? What torture was meted out to them! In order to massacre them it was necessary to proclaim that kulaks are not human beings. Just as the Germans proclaimed that Jews are not human beings. Thus did Lenin and Stalin proclaim: kulaks are not human beings.”

The Party’s reply, and its rationale for everything done to the kulaks, is summarized with exceptional frankness in a novel by Ilya Ehrenburg published in Moscow in 1934: “Not one of them was guilty of anything; but they belonged to a class that was guilty of everything.” (92-95)

Missiles and Mind-Sets: The Cold War Continues

I recall in the Nixon period how American envoys en route to Moscow on missions of quiet diplomacy about selected dissidents would rather anxiously ask the late Leonard Schapiro and myself whether the approach was the right one. We always answered no: a power could not base its policies on the hostage principle. As it was, the USSR, in exchange for making a few exceptions to its general line of conduct, was able to virtually silence the American government’s public voice on the broader issue.

One reason was certainly a deformation professionelle of the diplomatic establishment. Since diplomats’ forte is negotiation, they believe negotiation to be good in itself; and negotiation proper is a quiet matter. But the Soviets did what their interests required when the alternatives seemed less acceptable, and negotiation was merely a technical adjunct. To believe otherwise was to fall into the fallacy of the entrepreneur who thinks that a skeptical and experienced customer is more affected by the salesman than by the product. We need diplomats and salesmen to handle our policies and products, but there is more to international and economic affairs than that. Nor are these lessons obsolete.

For the capacity to envisage the alien is not distributed according to any of our usual intelligence tests. People can be able, clever, but not in the deepest sense wise. Examples of a run-of-the-mill academic or bureaucratic or even political “brilliance” are not seldom regarded as adequate in the responsible offices of the West, with disastrous results.

Shakespeare, in fact, was a better guide to the modern world than – in particular – certain circles with an inordinately powerful influence on the West, for he even produces characters, like Cassio, who typify the inability of inexperienced minds to understand the Iagos of the real world.

If Churchill was not deceived as to Hitler, this was not a matter of intelligence, but rather of a knowledge of history, and of evil. Chamberlain could not conceive of anyone whose attitudes were not more or less within the limits of those prevalent in the Midlands. What was and is essential is a grasp, if not of the particulars of a non-Western history, and political psychology, at least the notion that such may be totally different, totally aberrant, from our point of view. Some camouflage (as in the Soviet case) works better than others. All the same, the example of such phenomena as Pol Pot, Khomeini, Amin, Bokassa, Castro might have shown Western observers that their assumptions were not necessarily valid as to the whole range of political motivation. Ideas based on unsubstantiated desk work, or even mere assumptions of “rationality,” continued to undermine the West, and still apply in other contexts. (180-183)

“The Answer is Education”

But it is obvious that a high level of education in a general sense has often failed to protect twentieth-century minds from homicidal, or suicidal, aberrations. As we have seen, these have often been generated by men of high educational standing. And it has often been in colleges and universities that the bad seeds first bore fruit. Can anything more specific be urged? (215)

At a recent seminar on the much resented influx of certain American movies in France, my old friend Alain Besancon remarked that a hundred soft-porn products of Hollywood did less harm in his country than a single French philosopher had done in the United States. (221; 224-227)

Not all young, or old, people are susceptible to education. The Emperor Marcus Aurelius, Gibbon tells us, had this trouble with his son and successor, Commodus:

Nothing…was neglected by the anxious father, and by the men of learning and virtue he summoned to his assistance, to expand the narrow mind of young Commodus…but the power of instruction is seldom of much efficacy, except in those happy dispositions where it is almost superfluous. The influence of a polite age, and the labour of an attentive education, had never been able to infuse into his rude and brutish mind the least tincture of learning… Commodus, from his earlier infancy, discovered an aversion to whatever was rational or liberal. The masters of every branch of learning, whom Marcus provided for his son, were heard with inattention and disgust. (228)

An idea that has always been misleading is that mathematical theory is suitable to the analysis of society. Of course there are numerical data in such fields as economics and demography, though even there they need critical treatment. But we have long had a quite different phenomenon – the allocation of numerical figures to political and historical data. This goes so far as to give a “numerical value” to intangibles and abstractions. (232)

***

“Intelligentsia,” used in English, is a word with a foreign tang. It somehow, not unjustly, conveys a more bohemian milieu than that of the present-day “chattering classes” in America and Britain. I suggest (but will not irritate readers by overinsistence on it) “intelligentry.”

Using the word in a general sense, it is not coterminous with Western academe. But it is much involved in what may be broadly called education. First, it is more or less the “educated” section of the community. Second, it establishes the habits of mind of the media and of public discussion in general—which of course seeps down from, and (if queried) is validated by, selected academe.

What is mentally reprehensible about this intelligentry is just what made the Russian intelligentsia a century and more ago so inimical to reality and to serious thought. But that intelligentsia, as Adam Ulam points out, was in its vast majority against academic success, or academic employment. It was, in fact, a culture of dropouts, and proud of it.

Its present equivalent, though also hostile to the real world, largely appears within (as a sort of parallel world) a career-conscious and stipend-competitive modern academic caste. Thus we have, in the “disciplines” that were not available for exploitation by the early Russian intelligentsia, a different social basis. One can certainly imagine Chernyshevsky as a present-day Professor of Political Science; but on the whole one feels that the intelligentsia would have maintained its poverty unviolated. One unfortunate result of this academicizing of the intelligentry is, as we have noted, that many of them are under institutional pressures to accept the Ideas of the prevailing sects. The old Russian intelligentsia bullied and blackmailed its converts, and anyone else susceptible to such tactics, but at least it lacked this powerful weapon.

As Lionel Trilling once wrote: “This is the great vice of academicism, that it is concerned with ideas rather than with thinking,” and, he adds, “Nowadays the errors of academicism do not stay in the academy: they make their way into the world and what begins as a failure of perception among intellectual specialists finds its fulfillment in policy and action.”

…..But the way in which “informed” opinions may be considerably more misleading was demonstrated (in a way that horrifies one a good deal more than his date’s kiss horrified the young man quoted above) in an article in Scientific American as early as February 1982. The writer, dealing with the effects of low-level radiation, printed a table of thirty causes, or possible causes, of death, first with the true results as determined actuarially, then as perceived by three groups of educated citizens—members of the League of Women Voters, Students and Businessmen.

Both the Women Voters and the Students ranked nuclear power as the cause of the most deaths, well ahead of motor vehicles, smoking, handguns and all the rest. The Businessmen not so high, but still eighth, ahead of surgery, aviation, railroads and so on. The actuarial figures showed that nuclear power ranked twentieth, above mountain climbing but below contraceptives, with approximately 100 deaths a year (mostly, of course, from nonnuclear accidents in the industry). Motor vehicles killed around 50,000, handguns around 17,000, surgery around 2,800, railroads around 1,950.

An even more striking revelation comes with the imagined and the true figures for pesticides. The Women Voters ranked them ninth, which would mean about 2,000 deaths; the Students made them fourth – that is, around 17,000 deaths; even the Businessmen made them fifteenth – at the 200 level. The true figure was too small to register, but at any rate less than 10. (And spray cans, actually thirtieth of the thirty, were ranked as fourteenth and thirteenth, respectively, by the first two categories.)

And this is how, in America at least, the citizenry, and more especially those supposed to be among the better-educated or most concerned with public policy, envisaged important facts. They were thus totally misinformed. Their state of mind was stuck among the panics of the Middle Ages, when rumors that the wells had been poisoned by the Jews or the Gypsies swept whole populations of illiterate and backward peasants. When the California fruit crop was threatened by the pestiferous Medfly, it became necessary to spray large areas from the air with chemicals long proven to have no effect whatever on human beings. The state nearly let it go till too late, owing to protests not from the farmers but from the sophisticated townships of Silicon Valley. Similarly with the recent protests against a few pounds of plutonium in a spacecraft. A horrifying primitivism persists.

But Ug at least had no pretensions to be an Educated Man or an Informed Citizen. The problem is not so much that these nourish primitive fantasies as that they make no effort to correct these by means of the discriminating forebrains of which they are so proud; that they do not, when faced with a danger, take the rational course of seeking out the facts. As it is, they build up a picture of the facts – often a fallacious one – from what they find around; that is, in the media, which is to say the eye-catching mixture of fact, factiousness, guesswork and invention which forms the most readily available store of public wisdom.

It may be said that the public gets the media it deserves. Still, one may surely feel some repugnance for the new caste of cheap demagogues battening on the new superstitiousness. The Headmaster of Malvern wrote a few years ago that his boys, while highly skeptical about religion, were highly credulous about Chariots of the Gods. Unless there is a change in the public mind, the world is in trouble. The kiss of death may be dry rather than slobbery, but it is pretty unpleasant all the same. (234-237)