“Finally the boat stopped and was quiet for a time, but I continued calling until I heard answering voices. I thought them to be a group of soldiers out for an outing trip just for the fun of it. The finally found me, however, and got me down out of the tree; it was then I learned they were a searching party looking for me, and they had searched for two days. They later told me that they had no idea I was there and did not hear my calls until the motor had stopped. Jack Murray had the black Abo trackers with him and one of them wanted to stop and take a look at the shore at this point. Jack Murray did not want to stop but the Abo insisted so he pulled up to shore just to please the Abo. It was then they heard my yells for the first time. It seemed almost as if the Abo had had some sort of premonition of my being there and would not go on without first investigating.”

________________________________________

Paralleling the previous account of the shoot-down, survival, and return of Lieutenant John D. Landers, “this” post focuses on the survival of another 9th Fighter Squadron pilot whose story is related in Steve W. Ferguson and William K. Pasaclis’ Protect & Avenge: the 49th Fighter Group in World War II: First Lieutenant Clarence T. Johnson, Jr.

Johnson’s survival and rescue occurred half a year earlier than that of Landers: On June 15, 1942, during the 7th Fighter Squadron’s engagement with Zero fighters while intercepting G4M bombers over the Cox Peninsula, in Australia’s Northern Territory. Akin to the account of Landers in Protect & Avenge, Johnson’s bail-out and survival comprise four sentences of text. But, the full story of his survival, recorded in the historical records of the 7th Fighter Squadron – below – is at once dramatic, compelling, and powerful, given the starkly remote nature of the area where he landed by parachute, which in some ways seems as inhospitable – if not moreso? – than that of New Guinea. And, on an intangible level, his survival was attributable to an element of chance – and much more than chance alone – for he was ultimately returned back to the land of the living due to the intuition of a native Aboriginal tracker.

So, akin to the post about Landers, this post includes Ferguson and Pascalis’ account of the December 26, combat, below, followed by a verbatim transcript of Landers’ own story, from AFHRA Microfilm Reel AO 720. The post also includes an image from Protect & Avenge, and some maps from our lord and master (we love oligarchy!) Oogle.

________________________________________

THE THIRD RAID; JUNE 15th

The raiders repeated the same tactics with 21 fighters preceding 27 high flying bombers on the next day. Of the 28 Warhawks that went aloft, the 8th Squadron was again unable to break through the escorts and could not hit the bombers in the initial contact over Beagle Gulf. The 9th and 7th Squadrons again were heavily engaged.

The 9th FS was routinely up above Darwin proper with 2 Lts. George “Red” Manning leading the flight of wingmen Tom Fowler, Clay Peterson and “crocodile bait” Bob McComsey who had only recently returned to flight status. Red Manning was a short, sandy-haired German-American who loved to argue and set up a personal confrontation with an element of the 3rd Ku directly above the docks. After wingman Fowler joined in the fray, and McComsey with wingman Peterson followed, three ZEROs reeled out of the fight.

The enemy bombers had reached the docks by this time, dropped their ordinance and set fire to some of the nearby buildings. Even the convalescing Van Auken and his attending physician were forced to seek refuge beneath the Major’s hospital bed as bombs struck near the Kahlin dispensary. As the raiders turned west and began to accelerate in a descent over Cox Peninsula, they were met by the 7th Squadron.

The Screamin’ Demons were in two flights at 24,000 feet to ensure they would intercept the bomber formation which had been missed at their higher altitudes in the two previous raids. With Blue Flight led by ace Ops Exec Hennon, and Red Flight led by Squadron Deputy CO Capt. Prentice, they dived to the left rear quarter attack on the G4M raiders, but only Hennon and wingman 2 Lt. C.T. Johnson closed to within firing range before the ZEROs intervened. Johnson lost power momentarily and a ZERO quickly cut him off from his flight. The 3rd Ku aviator riddled the sputtering Warhawk, and Johnson tried to escape in the stricken fighter, but the Allison engine caught fire. He bailed out at nearly 18,000 feet over hazy Cox Peninsula (as of 2016, reportedly with a population of 15 people).

In the meantime, Red Flt Ldr Prentice and wingman 2 Lt. Claude Burtnette had engaged two escorts and both men opened fire, sending the ZEROs spinning down toward the Gulf. Second Lt. Gil Portmore in the second Red element also fired a broad deflection volley at a third ZERO which plunged downward, but the Demons were quickly overwhelmed. Red Flight was engaged by an enemy quartet and in the ensuing maneuvers, the Demon team split up. After shaking a ZERO off his tail, Burtnette of Blue Flight set off alone after the escaping bombers beyond Cox Peninsula, but was attacked again off the west shore by a 3rd Ku escort whose 20mm cannon fire blew off the ammo bay panel from the top of his right wing. He bailed out into the sea just west of Indian Island and floated in his Mae West vest while Capt. Hennon circled over his downed wingman until the ZEROs left the area. Burtnette reached Quail Island over two hours later and was spotted by a pair of RAAF Wirraway patrol planes who radioed his location to the Navy. The Australian lugger Kuru picked him up early the following morning from the north beach of Quail Island.

________________________________________

(Johnson’s original account, from AFHRA Microfilm Reel AO 720)

REPORT OF LIEUT. JOHNSON

7TH Pursuit Squadron

Report of Lieutenant Clarence T. Johnson, Jr., 7th Pursuit Squadron, who parachuted from his plane following engagement with the enemy. Lt. Johnson reports as follows:

We went up when the alert was sounded at about 11:45 a.m. June 15, and intercepted the enemy bombers at about 25,000 feet when they were heading away from where they had dropped their bombs. I attacked a formation of bombers picking on one that was lagging behind, came right in on his tail and firing a burst into the rear of the ship. The gunner was firing on me all the time and I evidently failed to hit anything as he kept us his fire. I then heard bullets in my plane ripping up the canopy and I thought I had been jumped by Zeros, so I cut away quickly but could not see any Zeros. I then made a deflection shot at another bomber in the middle of the formation and at that time my motor R.P.M. dropped off and then stopped completely smoke pouring out very badly. I was ahead of bombers and dropped down trying to gain speed to come up under the belly of the bombers, got the nose up and took a long shot at them but did nothing. I tried to head my plane back to the field, but the haze was so bad from forest fires etc., that I could not get directions just right. I was calling in on my radio all the time telling them I was coming down and tried to stay with it as long as possible. Evidently my canopy had been hit by bullets as there were holes ripped in it about six inches long. I pulled the emergency release and it flew open. I tried to get my canteen out but it was stuck in beside the seat and I could not get it loose before bailing out. The flame was then coming from the plane so I rolled it on its back and fell out. As I did so my leg hit the rudder or some other part. I opened my ‘chute immediately my boots being jerked off at the same time. I was at approximately 18,000 feet when I bailed out. While coming down I took a piece of paper from my pocket and tried to map out the area I was going down in. There had been several planes around up until this time but [I] did not see any after that. I landed in a burned out area with numerous stumps and trees sticking up, and I was lucky not to land in one. As I was coming down I thought I saw a stream of water about one and one half miles to the west, so I picked up and went in that direction and found a large spring in a clump of green trees, so I established camp there.

After resting a while I cut two panels out of my parachute and made ropes from the shroud lines and ripped up two white flags which I put in the top of the highest trees. Then I spread my parachute on the ground and made myself a cup of hot chocolate with water from the spring. I could not sleep until night and then I got up at about 3:30 or 4:00 o’clock in the morning with the intention of wandering toward the river which I thought I saw the day before. When I was almost there I discovered that I had left my compass at the camp along with my other equipment and decided to return for it before it was too late. I got lost and never found the camp. I wandered around for several hours and finally about noon I came upon the river again. I noticed the current flowing one way and thought it must be down stream, as I followed the river all that day and late into the night spending the remainder of the night on the banks. Early the next morning I saw planes flying around from time to time but they did not see me and I had no way of signaling them, so there was nothing I could do. I followed the river all the way and finally came upon the source of the stream instead of the mouth which I expected. It was fed by [a] large fresh water spring. I spent the night there. I arose early in the morning with the intention of walking the length of the stream to the coast where I expected to find food stores. I also thought of finding an Abo camp which I thought might be near, and where food etc., could be obtained. As I walked down the river I swam from side to side so that I could not miss any camps or food stores which might be on either side. Often I could not see the river for the dense undergrowth bushes which grew along the banks. On the fourth night I was getting very hungry and weak as I had had absolutely no food since the first day. When I bailed out of the plane there were four shells in my gun three of which I had shot. I was saving the last one for myself. I was in the water for about four hours trying to cut my way through the mangrove growth to get to the shore as I was positive the ocean was near. Finally made my way through the swamp where the mud was waist deep and I picked out a good place to spend the night. I was about to make camp when I heard what sounded like a motor boat gradually growing louder and louder. I thought this must be my last chance, so I automatically climbed a tree, fired my .45 and began yelling, but the boat kept going and I kept telling. Finally the boat stopped and was quiet for a time, but I continued calling until I heard answering voices. I thought them to be a group of soldiers out for an outing trip just for the fun of it. The finally found me, however, and got me down out of the tree; it was then I learned they were a searching party looking for me, and they had searched for two days. They later told me that they had no idea I was there and did not hear my calls until the motor had stopped. Jack Murray had the black Abo trackers with him and one of them wanted to stop and take a look at the shore at this point. Jack Murray did not want to stop but the Abo insisted so he pulled up to shore just to please the Abo. It was then they heard my yells for the first time. It seemed almost as if the Abo had had some sort of premonition of my being there and would not go on without first investigating. They made me some hot tea and heated me some stew – the first food I had eaten in four days. I was then taken to an Abo camp which was about a half day’s journey arriving in the evening. There was a government lugger across the bay where they took me for a good bed. Sub Lieut. Secrest [sic] was in command and they fixed up my feet and gave me a good bed for the night. The motor of the boat had gone out and they used sails to take us gradually toward Point Charles. Late in the afternoon the wind gave out and the current was against us, so they radioed in for a tow. They had also sent a message the evening before that I had been rescued. At about 7:30 a boat came out and towed us in and I was taken to the Darwin Hospital where I spent the night. I had gone five days without food of any kind – Monday noon to Saturday noon – when I was rescued. I kept trace of time by making nicks in my ring with a finger nail file.

I would recommend that some sort of signaling equipment be provided all pilots such as a very pistol, flares, or some sort of rocket. Also, in this section there always are fires burning, and if some sort of chemical could be had that would make a distinguishing colored smoke when placed in the fire, it would be easy to locate the lost pilot. I also advise all pilots to wear some sort of strap-on boots that cannot be jerked off when the pilot bails out of his ship. It is a good idea to wear coveralls as a protection for the legs and carry a gun and knife. Never wander off unless you know exactly what you are doing and always carry compass. Don’t throw away any equipment as you can make shoes out of parachute cover etc., and don’t cut the pants legs off. Above all don’t get excited or hysterical; think things out reasonably; use your head; and don’t get discouraged and give up. But don’t drive yourself and use all your energy in one day; conserve as much of your energy as you can. A slow steady pace will make your energy last longer.

CLARENCE T. JOHNSON, Jr.

2nd Lt., Air Corps.

________________________________________

A little over five months after Lt. Johnson’s rescue, the San Bernardino Sun published an article about his military service. The article was found at the California Digital Newspaper Collection of the University of California at Riverside Center for Bibliographical Studies and Research.

LT. JOHNSON, FIGHTING ARMY PILOT, HONORED

San Bernardino Sun

October 23, 1942

S.B. Youth Again Decorated for Valor in Action Against Japs in South Pacific

Lieut. Clarence T. Johnson Jr., son of Major and Mrs. C.T. Johnson of San Bernardino, again has been decorated for heroism while serving with the U.S. Army Air Force in Australia, according to word received in San Bernardino yesterday.

Previously he had been awarded the silver star for action near Darwin, Australia, June 13, and the purple heart for bravery in an aerial battle over Horn island March 14 in which he was wounded.

Lieutenant Johnson was awarded oak leaf dusters, his latest decoration, at Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s Headquarters. The presentation was made by Major-Gen. George C. Kenney.

SHOOTS DOWN ZERO

The award was in recognition of two recent encounters with the enemy. In the most recent action, Lieutenant Johnson was piloting a P-40 over Horn Island off northern Australia when he was Intercepted by a formation of Jap planes.

In a swift air battle, Lieutenant Johnson, succeeded in shooting down one zero fighter and then escaped without damage to his ship.

The silver star award was for his attack on 27 Jap bombers near Darwin. The assault was so successful that three or four enemy planes were caught in bursts from his machine guns and disabled. Lieutenant Johnson continued the attack after one motor of his ship [? – !] was disabled. His plane burst into flames and he was forced to bail out.

LOST IN JUNGLE

Upon landing, he found himself in wild jungle and swamp, through which he had to make his way unaided for six days before reaching his base.

His absence resulted in a report that he was “missing.”

Major Johnson, former San Bernardino mayor, is now in charge of an army recreation camp at Brunswick, Ga. Mrs. Johnson was executive secretary of the San Bernardino chapter of the Red Cross until she resigned a few months ago to join Major Johnson.

________________________________________

“7th FS cadre veteran C.T. Johnson (left), red flight leader Frank Nichols and veteran A.T. House cited at 14 Mile Field immediately after their part in the Lae convoy strike on January 7th.” (From Protect & Avenge)

__________

Australia! – care of Oogle maps. The general location of the Cox Peninsula, in the Northern Territory, is indicated by the red oval.

__________

Zooming in onto the Cox Peninsula, again denoted by a red oval. Note the city of Darwin to the east, separated from the Cox Peninsula by the Beagle Gulf / Port Darwin / Fannie Bay.

__________

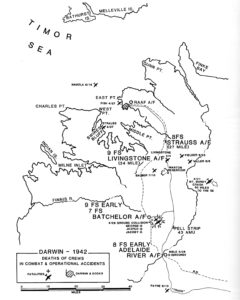

This map, from Protect & Avenge, gives a general view of geographic features surrounding Darwin, with the locations of 49th Fighter Group aircraft losses – which specifically resulted in fatalities to pilots or personnel – denoted, for a total of ten such symbols. Since Johnson survived, by definition there is no such symbol for his shoot-down.

__________

Oogling in for a map view of the Cox Peninsula. Though Darwin, the capital of Northern Australia, has appreciably grown since WW II (according to Wikipedia, the population is now over 147,000), note the barren appearance of the Cox Peninsula. Other than Wagait Beach, there’s not much in the way of human habitation.

__________

An equivalent air photo / satellite view of the above map.

__________

The northern shore of the Cox Peninsula, showing the location of the Point Charles Lighthouse, mentioned in Johnson’s report. The lighthouse faces the Beagle Gulf.

__________

Zooming in even further, the lighthouse is in the center of this image.

__________

And now for something completely different. (Albeit unsurprising in the world of 2021.) When I was putting together this post and perusing Oogle Maps / Oogle Street view, I couldn’t help but notice the presence of a McDonald’s Restaurant (on Bagot Road, in the Aboriginal Community of Bagot) in Darwin’s northern inner suburb of Ludmilla. Something tells me that this street had a markedly different appearance back in 1942…

References

Ferguson, Steve W. and Pascalis, William K., Protect & Avenge: the 49th Fighter Group in World War II, Schiffer Publishing, Atglen, Pa., 1996

Hess, William N., 49th Fighter Group: Aces of the Pacific, Osprey Publishing Company, London, England, 2014

AFHRA Microfilm Reel A0720, frames 1059 and 1060 (Johnson – 6/15/42)

Point Charles Lighthouse, at Geocaching Australia

Point Charles Lighthouse, at Wikipedia