“Upon looking down I realized the ‘chute had opened just in time, because I was right in the tree tops, having bailed out at a very low altitude. After landing in the trees which were about seventy-five to one hundred feet high I finally succeeded in cutting myself loose and scaled down three different vines before reaching the ground. The jungle was so thick I could not even find my jungle pack which I had pitched from the tree.”

________________________________________

A central, natural theme of the literature of military aviation – regardless of the era, geographic theater, or level of technology – has revolved around accounts of aerial combat, particularly between fighter planes. However, even with the fascination inherent to such tales on historical, intellectual, and even emotional levels, they’re often characterized by a kind of… Well, on a literary level … sense of “roteness” … to the point where an author could “swap out” opposing pilots aircraft types and nationalities; even change the very conflict in question, and create a tale having a similar – if not the same? – literary and emotional impact.

However, in another respect, the literature of military aviation is often characterized by a theme of a different nature. That lies not in stories about aerial victories, military awards, technology, camouflage and markings, and aircraft “nose art”, but instead in accounts about the survival of aviators who did not, n e c e s s a r i l y (!) emerge completely victorious – or victorious at all, in any way! – from engagements with an enemy. Stories of endurance, perseverance, and survival in settings where climate, geography, remoteness from immediate aid, and sometimes a combination of injury and isolation render a downed pilots’ chance of survival problematic at best, and minimal at worst. Of course, this doesn’t even begin to take account of the possibility of capture by enemy forces, let alone the sometimes much worse threat posed by enemy civilians…

Well, there are myriads upon myriads (upon many?!) such tales in the popular literature of military aviation, and in “this” post you’ll be able to read such an account: It’s the story of the shoot-down and survival of Lieutenant John D. Landers on December 26, 1942, during the 9th Fighter Squadron’s (49th Fighter Group’s) encounter with Ki 43 Oscars of the Japanese Army Air Force’s 11th Sentai over eastern New Guinea. The story of this aerial engagement can be found in Steve W. Ferguson and William K. Pascalis’ Protect & Avenge: the 49th Fighter Group in World War II (1994), where Lander’s experiences – after bailing of his P-40 – comprise a single paragraph. Having access to the original historical records of the 9th Fighter Squadron (in digital form, from the AFHRA), I was able to find the account composed by Landers himself, after his rescue and eventual return to the 9th Fighter Squadron.

This is not at all meant as a criticism of Protect & Avenge, for this fine book (any substantive aviation history, really) would be both prohibitively lengthy and expensive were it to include each and every facet of information from historical records.

The post includes Ferguson and Pascalis’ account of the December 26, combat (immediately below) followed by a verbatim transcript of Landers’ own story, from AFHRA Microfilm Reel AO 720. Also included are images from Protect & Avenge, William N. Hess 49th Fighter Group: Aces of the Pacific, and some maps and air / satellite images showing New Guinea, zooming in on the location of Pongani village, which location is central to the story.

As for 1 Lt. Lieutenant John D. Landers himself? He eventually rose to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, being credited with 14.5 aerial victories: six in the Pacific while serving in the 9th Fighter Squadron, and eight and a half in the European Theater while serving with the 38th, 357th, and 78th Fighter Squadrons, of the – respectively – 55th, 355th, and 82nd Fighter Groups of the 8th Air Force.

________________________________________

THE BEST VS. THE BEST; DECEMBER 26, 1942

As the 49ers shuttled men and planes at Moresby, the JAAF 11th Sentai began their active participation in the operations from Malahang strip, northeast of Lae Village. After a number of small reconnaissance flights, the OSCARs flew a sweep in force to the south in the improved weather of mid-morning on December 26th.

Likewise, the second Warhawk patrol lifted off from the fields at Port Moresby between the intermittent rain showers and coasted over the Owen Stanley Mountains toward the Buna area. Senior Lt. “Big John” Landers led a dozen Warhawks with White Flight at 14,000 feet, Blue Flight at 10,000 and Red Flight at 8,000, all meant to orbit over Buna. Just as they arrived, the Dobodura air controller urgently called for fighter cover. “ZEKEs” were strafing the landing area and attacking a flight of RAAF Hudson transports, one of which carried none other than Gen. Blarney, head of the Allied army in New Guinea. Landers ordered “tanks off” and the Flying Knights peeled off for the interception.

The “ZEKEs,” of course, were the Lae OSCARs that had caught the Hudsons at low altitude. As the OSCARs separated momentarily in their mad chase after the RAAF bombers, Landers’ Red and Blue Flights burst out of the hazy overcast and struck the enemy over Dobodura airfield. The Knights latched onto their targets and a vicious dogfight raged from 5000 feet down to the tree tops.

Blue Flight engaged first as veteran element leader Jim “Duckbutt” Watkins and wingman Art Wenige held together to make two coordinated passes against the OSCARs. Blue Leader Bill Levitan and wingman Bill Sells separated in the first hard turn, but they quickly bested a pair of enemy fighters beneath the hazy overcast. Before the Blue quartet was forced to break off due to low ammo and fuel, Levitan, Sells, Watkins and Wenige each claimed to have destroyed one the assailants. As for Red flight, things turned out differently for Darwin veteran John Landers.

In Red Flight’s attack descent through the broken overcast, Landers’ elements lost formation and remained dangerously separated throughout the fight. In his first combat engagement, wingman 2 Lt. Bob McDaris claimed a “ZEKE” destroyed and another heavily damaged, but failed to relocate his flight leader. “Mac” made a solo retreat for Moresby. Likewise, 2 Lt John “Baggie” Bagdasarian had chased an OSCAR off the tail of Blue Flight’s Watkins, but Baggie’s old stager could not stand the strain and he set the P-40E with its blown Allison engine down safely at Dobodura.

Landers, flying #75 THE REBEL (formerly CO Irvin’s old ship), plunged right into the midst of a regrouping flight of six OSCARs, and took them all on at once. Big John’s wild aerobatics in the REBEL so startled his opponents that he bested two of them before the odds overcame him. One of the sentai masters finally swung his nimble Ki-43 in behind Landers and the lone Knight could not shake free. The REBEL was perforated by a long, accurate stream of 7mm tracers.

Landers broke down and away for the safety of the foothills to the south, but his pursuer riddled the REBEL again before he could drop behind the crest of the forested terrain. Big John pulled back his canopy, stepped out on the wing and was swept off in the slipstream at 1000 feet of altitude. He was jolted in the straps below the burst of his chute and fell into the dense forest due east of the coastal village of Pongani.

The hefty pilot survived a rough tumble through the limbs of a tall tree and came to rest in a dense thicket that took several hours to negotiate. Once able to find better footing in a stream, after three days, Landers eventually waded to a small village not far from Pongani. The tribal elder there graciously took a personal liking to the six foot, four inch “plenty whitey goodfella.” They gave the blond giant food and shelter for the night, and on the next day, a native party escorted Landers down the trail to Pongani village. Big John soon caught the next transport flight for Port Moresby.

________________________________________

(Landers’ original account, from AFHRA Microfilm Reel AO 720)

Combat Report of 1st. Lieut. JOHN D. LANDERS, 0-431968,

9th Fighter Squadron, 49th Fighter Group.

On December 26, 1942, the red flight of which I was leader and including Lt. R.A. Francis, Lt. R.A. McDaris and Lt. W.D. Sells took off at 0945 o’clock for patrol over Buna. My flight was split up due to radio disturbance and poor reception, leaving two two-ship elements. We were patrolling at about 3,000 feet. At 11:15 o’clock Wewoka called and said that enemy aircraft were strafing Dobodura. At 11:17 I dropped my belly tank, turned on my gun switches and dove down to 1,000 feet directly behind a Zero. I got to within 200 feet of the Zero before I fired. As I squeezed the trigger a trail of black smoke came from the Zero and it immediately blew up. This was the first of three Zeros which were attacking an allied transport. I turned into the second one which was also in a turn. I fired a burst ahead of him and through him. I turned back around and followed him and got another burst into him as I was turning to my left and he was turning into me. While firing the second bust, which was a long one, I could see that the Zero was smoking, and I expected it to blow up like the first one but it burst into flames and went down. At this time I observed about eighteen to twenty holes in my left wing and immediately banked over to my left at which time I saw a third Zeke firing at me. I pulled over this Zero and started into an intense dog fight at about 1,000 feet. He hit me with three different bursts, all deflection shots, and I felt certain that this was one of “Tojo’s hot pilots”. One burst hit the wing, another his across the nose and in the engine and the other one across my tail section. My engine was smoking badly from underneath. During the latter part of the dogfight I was beginning to lose power, so I turned away from the Zero toward a gap between the mountain tops of the Hydrographer’s range and the clouds, just a small opening, but I headed right for it. My engine started running rougher and smoking more, so I prepared to bail out if my engine stopped. Just before I got to the mountain range my engine started missing fire and then quit altogether just as I cleared the mountain top. I lowered my nose to keep from stalling out, rolled back my canopy, cut my switches, unfastened my safety belt and prepared to jump. I banked to the left about 15 degrees, stuck out my left arm and shoulder and head and let the wind suck me out. About half way out my feet got caught and I had to kick them free. Just as I saw the tail of my plane go by I pulled the rip cord.

Upon looking down I realized the ‘chute had opened just in time, because I was right in the tree tops, having bailed out at a very low altitude. After landing in the trees which were about seventy-five to one hundred feet high I finally succeeded in cutting myself loose and scaled down three different vines before reaching the ground. The jungle was so thick I could not even find my jungle pack which I had pitched from the tree. While in the tree I could hear a running stream which seemed very near but which took me forty-five minutes to reach due to the intense jungle. Upon reaching the stream I started walking up stream to a village which I had sighted while in the air. After walking for six hours I came upon a native woman with two kids. She was so startled to see me that she started bellowing like a cow until the whole village came. They led me to a shack and built a fire just outside; it was raining. We sat around and made signs and I tried to make myself understood as to what I wanted done and where I wanted to go. There were only three words the natives in the village could say, namely: Jap, American and machine gun. I gave them many gifts, shiny objects. They fed me paw paw, bananas and sweet potatoes. We then went back to the village on a mountain about a mile from where I bailed out. It only took us about two hours to reach this destination by native trails. They showed me .50 calibre ammunition they had taken from my plane, approximately where it had landed. This proved a help in getting them to lead me to the plane later. I made them understand that I wanted them to take me to my plane the following day. Just before dark a group of natives came up with my parachute, which they had removed by climbing the tree. The ‘chute was badly torn from having caught on the branches. I learned it might be a good idea to remain with the ‘chute because the natives seemed to have no trouble in finding the ‘chute, as they indicated that they watch the sky when hearing combat. I later used part of the ‘chute as cover.

There was only one shack in this village on the mountain top which was about two miles actually from the village. This shack was a grass hut about twenty by fifteen feet and about four feet high. That night when I got ready to go to bed they cleared a place in one of the corners, laid a mat down for me to sleep on, gave me the chute to cover with and the air cushion for a pillow. They fed me again by cooking green bananas over the fire and sweet potatoes. There were 23 natives and myself in this hut those two nights. The first morning in the jungle we awoke at seven o’clock. The men, women and children, the latter ranging from four and five up, sat around for an hour and smoked. At eight o’clock we started eating, a meal which consisted of cooked bananas, sweet potatoes and paw paw. Then they started combing their hair and primping up for the day; the men shaved with old double edge blades which upon examination must have been a pulling action. Each man carried a mirror. This lasted until nine o’clock and I afterwards learned that this was daily routine with this group of natives.

We started out on a march to my plane which lasted about two hours. Upon arriving there I could see that the plane was beyond saving. The plane did not burn but was completely demolished. I especially checked on radio equipment and everything was completely broken up including instruments. I sat around until about two o’clock and watched them take the souvenir pieces from the mountain side. I was amused to note that the women carried the whole load back to the camp. I spent that evening in the hut with the twenty-three natives. It was understood that they were to take me to Gore the next morning.

I had six guides from the village. We stuck to native trails throughout the entire march over the mountains and streams. A stream was always at the foot of the mountains and I was well supplied with good clear drinking water from them. Native food was plentiful, consisting of bananas and paw paws. At the villages we passed through I was given coconut milk to drink. The first night we slept in a deserted village of about fifteen shacks. The following morning my guides obtained other guides and the original group returned to their village.

In each village I slept in a shack which was set aside for visitors. My guides, myself and the owner of the shack were the only ones who slept there. The wives and children went elsewhere for the night. They were always expecting me from one village to the next by the guides shouting from mountain tops. Preparations would be made, such as having a boy climb a tree to get me a coconut and the like. The natives took especial interest in my gun and wanted me to shoot all the birds along the trail which they would keep to eat later.

On my fourth day I found a native who could speak very good English. I asked him if he would guide me the rest of the way to the coast but he replied, “I would if I could but I don’t think my wife would let me.” He used Aussie slang freely and said that his wife spoke as good English as he. He was amused and happy that we could carry on a conversation and that the other natives in the village could not tell what we were talking about. The next morning he sent another boy in his place to guide me. He said he could not go but for me to sleep in the fourth village from there that night, and that the following day I could make the coast. My last day we climbed up mountains for three hours and went down hill for seven hours, and arrived at a small American Outpost about 4:30 that afternoon, December 31st.

An interesting thing about the mountains was that at about 11:30 every day it started to rain. When we were on top of the mountains we would be walking through a dense fog but by the time we could get to the bottom it would be clear but still raining. I was wet about twenty-four hours of the day despite keeping a fire burning all night.

I remained with our troops at Pongoni until picked up by Captain Peaslee on January 2nd.

It is suggested that arrangements me made to carry salt tablets and handi-tape in pilot’s jungle kits. In my particular case the natives found my parachute before they found me. It might be a good idea to remain with your parachute for a few hours at least. Leggings should be worn by pilots while flying to be sure of having them in event of emergency. Also, it might be advisable to include small items, such as, razor blades for gifts for the natives. These items could be inserted in the back pad or jungle kit.

JOHN D. LANDERS

1st Lt., Air Corps.

__________

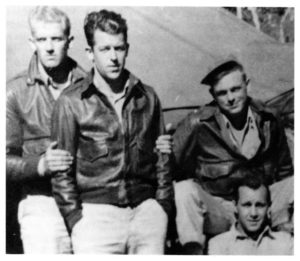

“(Left to right) 2 Lts. John Landers, Jack Donaldson, flight leader Andy Reynolds and John Sauber. Donaldson replaced fallen Livingston of the original flight team which later became the high scoring Blue Flight. ” (Photo from Protect & Avenge)

__________

“Java veteran Capt. ‘Bitchin’ Ben S. Irvin, who was 9th FS CO for a short period in Darwin, leans against the wing of his P-40E (41-25164, “white 75”), “The Rebel”, showing its prominent Pegasus fuselage art. Irvin had claimed two confirmed victories with the 17th PS in February 1942 before joining the 49th FG. Irvin did not add to his tally while leading the 9th FS, and returned to the US in late October, 1942” (Photo from collection of John Stanaway, in 49th Fighter Group: Aces of the Pacific)

__________

“The Rebel” in flight (Photo from Protect & Avenge)

__________

Color profile of “The Rebel”, by Chris Davey, from 49th Fighter Group: Aces of the Pacific.

__________

“Brig. Gen. Paul B. Wurtsmith, Commander 5th Fighter Command, congratulates Lt. John D. Landers, Joshua, Texas, of the 49th Fighter Group after presenting him with the Purple Heart. He also received the Oak Leaf Cluster, Air Medal, Distinguished Flying Cross and Silver Star at a ceremony held at Dobodura Airfield (Horando), near Port Morsesby, Papua, New Guinea. 18 May 1943.” (79118 AC / A32295)

__________

John D. Landers, now Colonel John Landers, serving in the 78th Fighter Group, as pictured in Duxford Diary (American Air Museum in England document 16844)

__________

New Guinea. The location of the general area of Pongani village is denoted by the red oval.

Zooming in for a closer view of the location of Pongani village…

…and, even closer.

An air photo / and or satellite view at the same scale as the above map….

…followed by an even closer view.

References

Ferguson, Steve W. and Pascalis, William K., Protect & Avenge: the 49th Fighter Group in World War II, Schiffer Publishing, Atglen, Pa., 1996

Hess, William N., 49th Fighter Group: Aces of the Pacific, Osprey Publishing Company, London, England, 2014

USAF Credits for the Destruction of Enemy Aircraft – World War II, USAF Historical Study No. 85, Albert F. Simpson Historical Research Center, Air University, 1978

AFRHA Microfilm Reel AO 720, frames 1017 through 1020 (Landers – 12/26/42)

P-40E-1 41-25164 “The Rebel” / “75”, at Pacific Wrecks.com

Pongani village, at Wikipedia

Pongani Airfield, at Pacific Wrecks