Years ago, I wrote to Monogram Models, in Morton Grove, Illinois, asking for information about the design and manufacture of plastic model kits. I was hoping that Monogram possessed “in house” literature and promotional material, with a specific focus on the creation of models of military aircraft, and, military (armored and “soft-skin”) vehicles. Of particular interest was the “origin” – as it were – of such kits as Monogram’s 1/48 P-38 Lightning or P-39 Airacobra, which, in terms of quality, detail, and options, embodied major advances over plastic kits produced only a few years before, whether by Monogram itself or its competitors.

Monogram’s customer relations department soon replied, sending me a reprint of an article from – to my surprise and disappointment – Old Cars magazine. (“? – !”) Rather consistent with its title, the article covered the creation of car kits, rather than models of planes, tanks, warships, or spacecraft. (“Let down!”)

Though my curiosity wasn’t satisfied – at least directly – the reprint I received was nonetheless interesting, for its description of the design and manufacture of model cars was equally and entirely relevant to the creation of plastic kits of other genres.

Certainly; obviously, the world of plastic modelling has enormously changed since the 1960s and 70s. Monogram (as well as its competitors – Revell (Venice, California), Aurora, Hawk, Renwal, and Lindberg) no longer exists, the company’s Morton Grove headquarters / manufacturing facility having been demolished years ago. I would not be surprised if the buildings that once housed the corporate headquarters and manufacturing facilities for the other above-mentioned companies likewise remain only as memories. Another, altogether unsurprising change: Contemporary kits of military aircraft or automobiles – in most any scale – are no longer quite available for – ahem! – $3.50.

In that sense and spirit, the Old Cars article presented below provides a glimpse of a world that has largely – albeit not completely! – “gone by”.

____________________

Old Cars

The Twice-Monthly Newspaper of the Hobby

April 16-30, 1974

Old Cars readers who spend many relaxing hours absorbed in building faithfully reproduced scale models of their favorite cars sometimes probably marvel at the detail and accuracy of the tiny replicas.

They didn’t get that way by accident. The planning, tooling, and manufacturing of the little model you purchased at the local hobby shop for $3.50 or so in some cases involves as much thought, accuracy, and time as their full-sized counterparts.

That’s what we found out when we recently visited one of the nation’s largest model manufacturers, Monogram, in Morton Grove, Ill.

Except for being locked into the styling of the car as it was produced, the production of a model takes on many of the overtones of an auto manufacturer planning a new car. In the case of a scale model classic or antique car, the vehicle is decided upon and the real article located to serve as a model for the model. Monogram design people are dispatched for an extensive photo session with the car, then return to the workshop where a prototype is hand-built.

Once the prototype is completed, there are discussions on the feasibility of marketing the model. If it gets the nod, three-view drawings of the car are carefully rendered and cost estimates for production are submitted. Then it’s go or no-go, based on what total production costs will be. Like we said earlier, it has all the overtones of Detroit planning a new car.

Monogram, with its 1/24 scale, is somewhat of a maverick in the model-making industry. Other companies use a 1/25 scale for their products, but Monogram’s original models were done in 1/24, and the company simply chose to stay with this figure.

Detroit needs its dies and stamping to bring out a new model, and Monogram must have intricate molds to build the component parts of their cars. This is an internal operation, too, and a visitor sees skilled tool and die specialists working carefully with micrometers and pantographs, adjusting to the thousandth of an inch, so that hubcaps all conform to the same size and shape, and the plastic tires carry symmetrical tread.

Instead of molding one piece at a time, though, the model company plans their mold-making so a number of similarly-colored pieces can be produced in one pressing. Complicating the mold-making is the need for adequate water passages, just as in an engine block, so the mold and the plastic won’t distort, warp, or overheat during manufacturing.

Development from raw blocks of metal to finished mold takes from 16 to 18 weeks, Monogram officials said, and the final process of polishing the mold to a mirror-smooth surface is done with diamond dust. A set of molds for a single kit can cost more than $50,000.

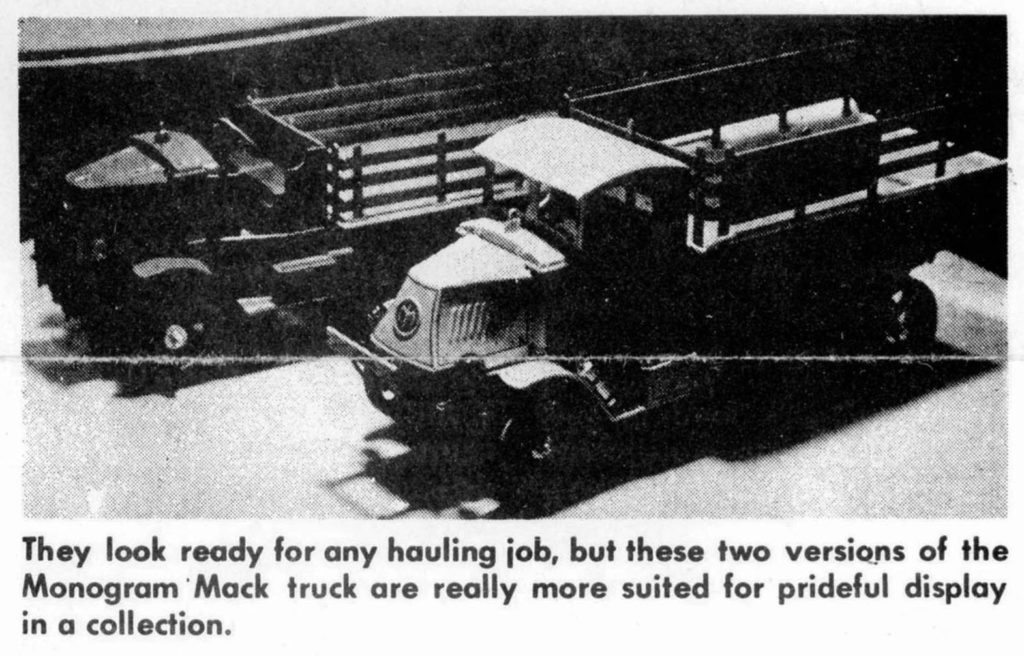

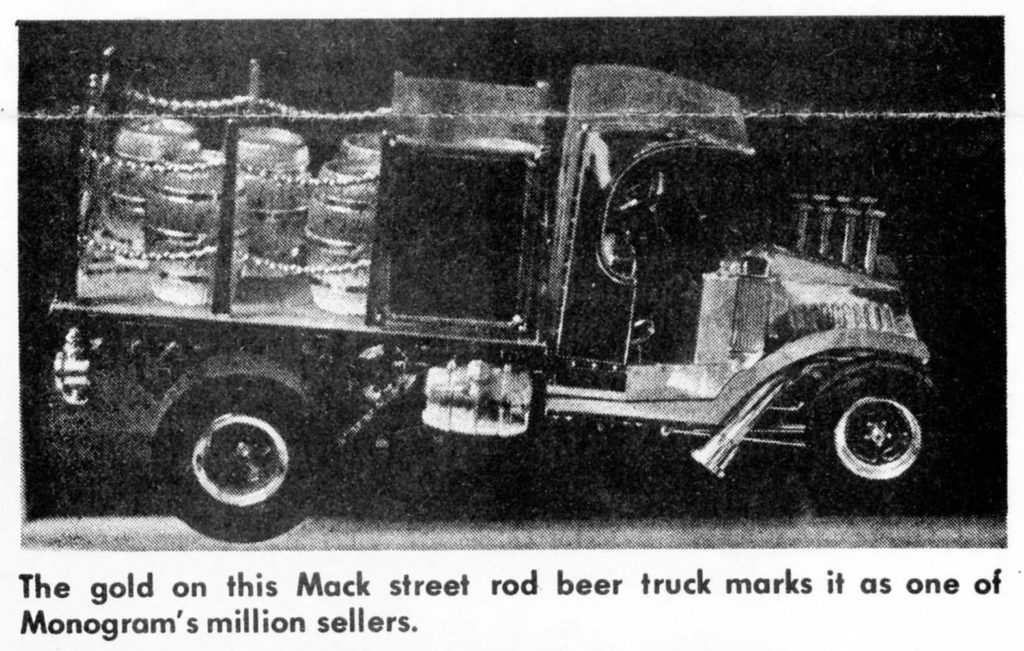

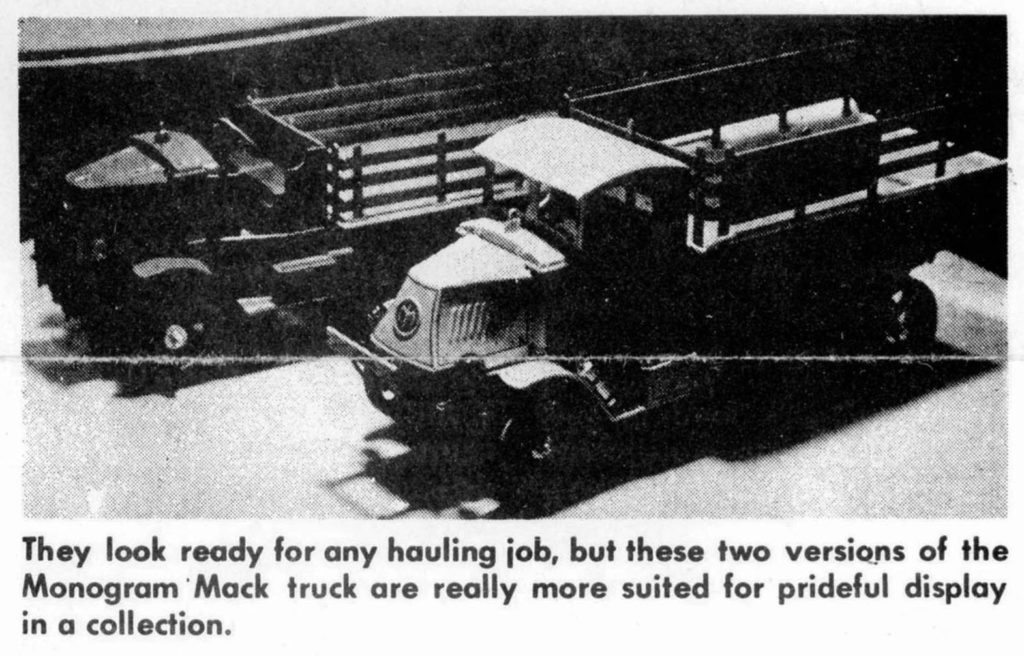

Sometimes they can cost even more. One of Monogram’s latest models, the Mack Bulldog stake truck, required molds that cost nearly $75,000 for the complete set. For the Duesenberg SJ town car Monogram recently introduced five molds were required: a white model for the whitewall tire inserts, black and green styrene, a clear mold, plus a mold for the tires.

Depending on the size and intricacy of the parts to be pressed, the polystyrene plastic used in Monogram models may be subjected to as

Color chips used for molding the parts are very critical. Monogram custom-mixes some colors in their own small cement-style mixers to assure consistent color. Just one off-color chip among thousands, a Monogram official said, will change the hue of the entire color batch, with disastrous consequences to production of model kits using that color of plastic.

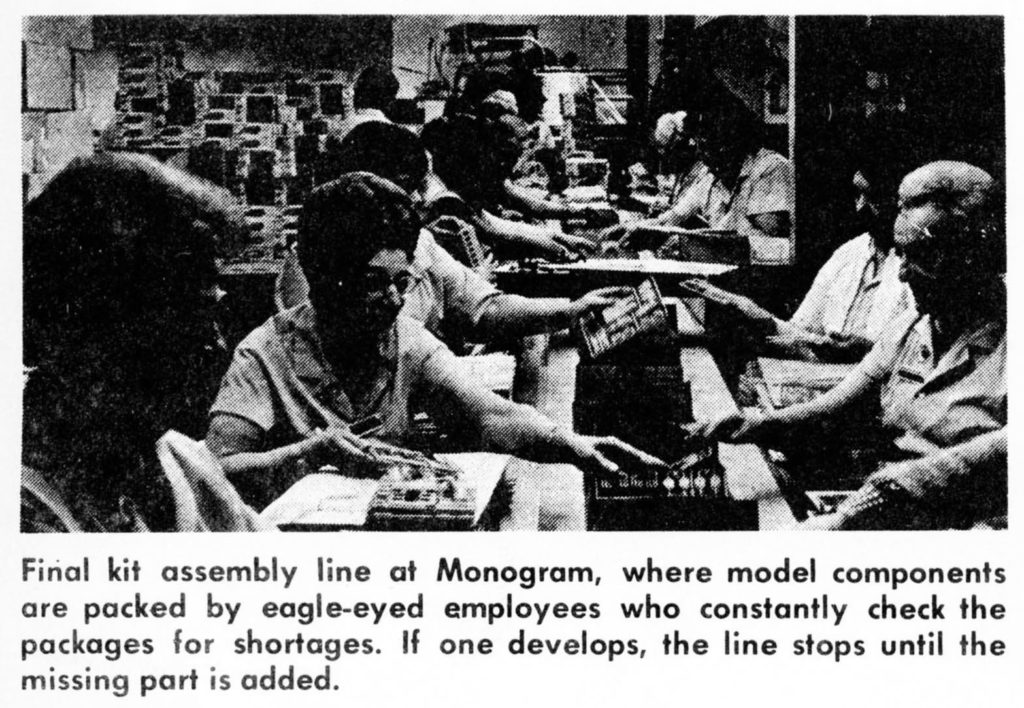

When the kit parts come out of the press, they are checked for consistency and quality, then passed on to the kit assembly line.

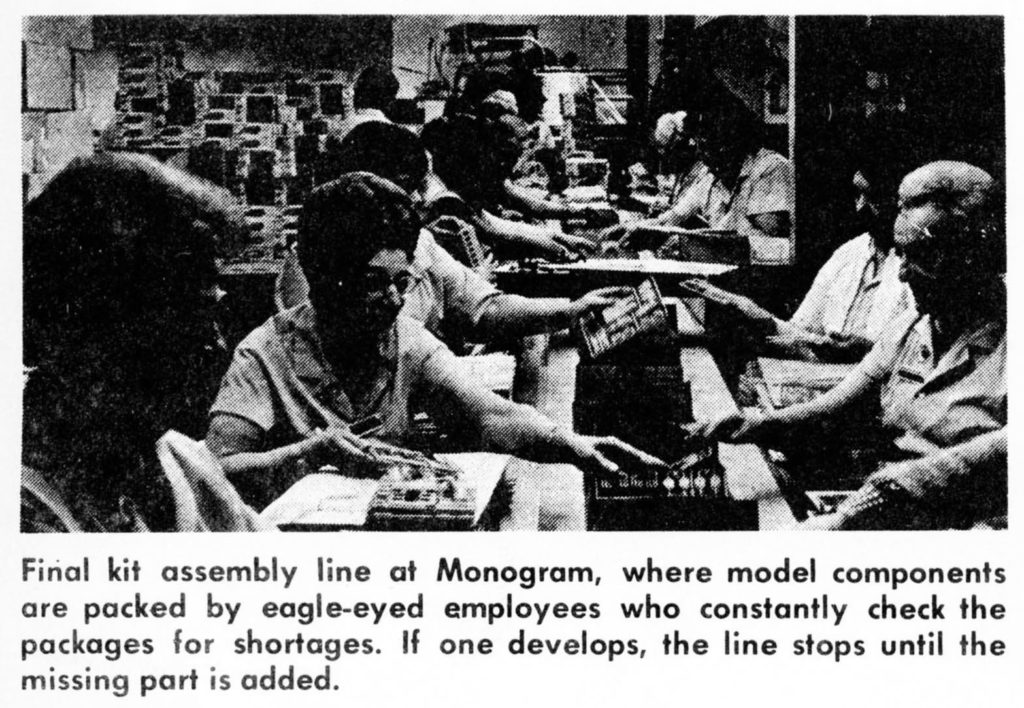

Situated in a large, clean, cheery room, the assembly line is nothing like those in Detroit. It’s quiet, with an air of humming efficiency, rather than frantic activity, and the ladies who staff the line work smoothly and quietly at their tasks. But the pace is deceptive, for we were told that an average of 2,000 kits per hour were packed, wrapped, and dispatched on each of the 3 production lines every working day.

That adds up to a potential of 50,000 to 75,000 completely-packaged kits per day when all the lines are in full operation.

Quality control is a personal watchword, too, and each packer acts as a check on the work of the employee preceding her on the line, making sure each kit contains the proper components when it reaches her station.

If it doesn’t, the line stops, the missing part is put in the kit, and off the line goes again. Naturally, the responsibility for the completeness of a kit increases as the line nears the end, and humans being humans, mistakes and omissions sometimes will happen. That’s why Monogram plucks a random sample of 10 kits off the line each hour to check and see that they are complete.

But what if a kit comes to a customer with a missing wheel, or tire, or bumper, despite all these precautions? No problem, says Monogram. The customer should simply write the factory and tell them what’s missing. Monogram will send the missing part pronto, no questions asked.

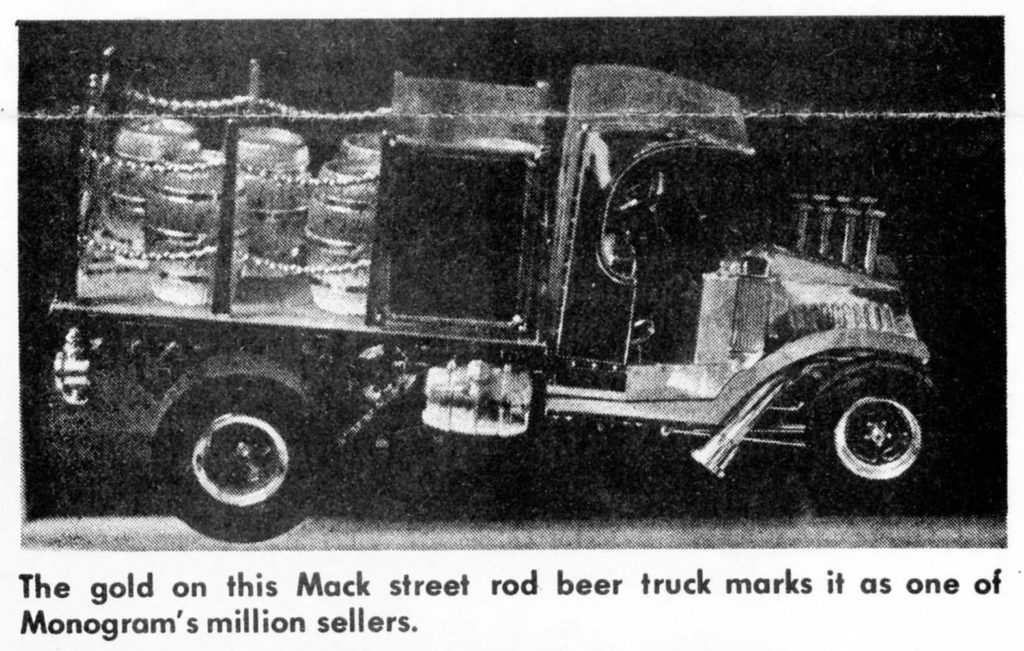

Monogram will be celebrating its 30th year of model manufacturing in 1975. The company’s first products were balsa-wood ship models. After their initial success with the ships, the company branched into airplanes, then cars, and has recently introduced a 1/32 scale World War II armor troop and vehicle series. The company has enjoyed an impressive number of “million-seller” models, with a sample of each on display at their home office but, strangely, none of their classic car series have yet reached the magic figure.

Scheduled for introduction in July is a variation on the Mack, a Bulldog AC Texaco gasoline tank truck. This particular model could possibly become a significant piece of Americana, reminding us of the days when gasoline was plentiful.

In June, Monogram will introduce their new Special Interest Car series. The first three models in this group will be the ‘58 Thunderbird convertible, a 1930 Ford cabriolet, and a 1930 Ford 5-window rumble-seat coupe. We’ve seen them, and they’re authentic enough to pass muster at a national meet.

Model-builders have every right to marvel at the detail, intricacy and authenticity built into their economically-priced kits. There are some dedicated people in Morton Grove, Ill., who work very hard so you’ll do just that.