Sometimes, fiction can foresee fact.

Sometimes, entertainment can anticipate reality.

This has long been so in the realm of science fiction, a striking example of which – perhaps arising from equal measures and intuition and imagination – appearing in Astounding Science Fiction in mid-1949. That year, Eric Frank Russell’s three-part serial “Dreadful Sanctuary” was serialized in the June, July, and August issues of the magazine.

(Astounding Science Fiction, June, 1948; cover by William F. Timmins. Note Timmins’ name on the “puzzle piece” in the lower left corner!)

(Astounding Science Fiction, June, 1948; cover by William F. Timmins. Note Timmins’ name on the “puzzle piece” in the lower left corner!)

(Astounding Science Fiction, July, 1948; cover by Chesley Bonestell)

With interior illustrations by William F. Timmins, the story, set in 1972, is centered upon the efforts of protagonist John J. Armstrong – an iconoclastic combination of entrepreneur, inventor, and unintended detective – to accomplish the first successful manned lunar landing (as his entirely private venture) in the face the inexplicable mid-flight destruction of each of his organization’s spacecraft. Armstrong doesn’t fit the cultural stereotype of inventor or scientist. As characterized by Russell, “Armstrong was a big, tweedy man, burly, broad-shouldered and a heavy punisher of thick-soled shoes. His thinking had a deliberate, ponderous quality. He got places with the same unracy, deceptive speed as a railroad locomotive, but was less noisy.”

While Russell’s story commences as a solid – and solidly intriguing – mystery, effectively conveying a sense wonder; with characters who portend to be more than two-dimensional; the events, plot, and underlying tone gradually change. With the installments in the magazine’s July and and August issues, what had been a story with an eerie undertone of Fortean inexplicability, technical conjecture (such as the “ipsophone”, a video-telephone imbued with aspects of artificial intelligence – cool! – we’re talking 1948!), and a well-crafted mood of impending threat, gradually and steadily falls flat. A pity, because to the extent that the story succeeds – and in parts it does succeed, and creatively at that – it does so far more as a hard-boiled (and very ham-fisted) detective tale than science-fiction.

Regardless of the story’s literary quality (I don’t think it’s ever been anthologized) the physical and psychological presence of the aptly named Armstrong (“arm”?! “strong”?!) remain consistent throughout. Iconoclastic and independent, he’s extremely intelligent, and if need be, a man capable of brute intimidation, self-defense, and violence. He is also canny, cunning, and psychologically astute.

It is these latter qualities that lead to Armstrong’s discovery – after meeting with a police captain – of a most intriguing device, at his residence in the suburbs of New York City.

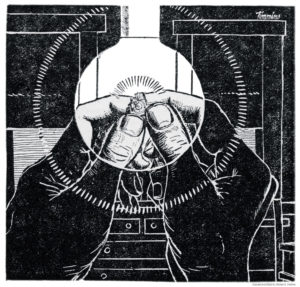

Correctly suspicious of surveillance by adversaries, on reaching his residence, “…Armstrong cautiously locked himself in, gave the place the once-over.

“Knowing the microphone was there, it didn’t take him long to find it though its discovery proved far more difficult than he’d expected.

“Its hiding place was ingenious enough – a one hundred watt bulb had been extracted from his reading lamp, another and more peculiar bulb fitted in its place.

“It was not until he removed the lamp’s parchment shade that the substitution became apparent.

“Twisting the bulb out of its socket, he examined it keenly.

“It had a dual coiled-coil filament which lit up in normal manner, but its glass envelope was only half the usual size and its plastic base twice the accepted length.

“He smashed the bulb in the fireplace, cracked open the plastic base with the heel of his shoe.

“Splitting wide, the base revealed a closely packed mass of components so extremely tiny that their construction and assembling must have been done under magnification – a highly-skilled watchmaker’s job! The main wires feeding the camouflaging filament ran past either side of this midget apparatus, making no direct connection therewith, but a shiny, spider-thread inductance not as long as a pin was coiled around one wire and derived power from it.

Illustration by William Timmins (July, 1948, p. 101)

Illustration by William Timmins (July, 1948, p. 101)

“Since there was no external wiring connecting this strange junk with a distant earpiece, and since its Lilliputian output could hardly be impressed upon and extracted from the power mains, there was nothing for it than to presume that it was some sort of screwy converter which turned audio-frequencies into radio or other unimaginable frequencies picked up by listening apparatus fairly close to hand.

“Without subjecting it to laboratory tests, its extreme range was sheer guesswork, but Armstrong was willing to concede it two hundred yards.

“So microscopic was the lay-out that he could examine it only with difficulty, but he could discern enough to decide that this was no tiny but simple transmitter recognizable in terms of Earthly practice.

“The little there was of it appeared outlandish, for its thermionic control was a splinter of flame-specked crystal, resembling pin-fire opal, around which the midget components were clustered.” (July, 1948, pp.116-117)

I’ll not explain the origin of this device (it’d spoil the story should you read it!), but suffice to say that in the world of the “Dreadful Sanctuary”, things and people are not as they seem, in terms of origin, nature, and purpose.

In our world, however, it seems that Eric Frank Russell created a literary illustration – at least in terms of its diminutive size and the delicacy of its fabrication – of what would in only a few years be known as the integrated circuit.

Sometimes, imagination can anticipate the future.

References

Chesley Bonestell (at Wikipedia)

Eric Frank Russell (at Wikipedia)

William F. Timmins (at Pulp Artists)

Astounding (Analog Science Fiction and Fact)

Integrated Circuit (at Wikipedia)