The prior post – covering photographs of the loss of the 42nd Bomb Squadron B-24 Liberator Dogpatch Express – ended on an uncertain note.

Both the Missing Air Crew Report and 42nd Bomb Squadron history present detailed accounts of the bomber’s loss. However, both documents are ambiguous about the specific cause of the aircraft’s loss, let alone what ultimately befell the few survivors of the plane’s ditching. Given that PBY rescue planes later reported neither survivors nor wreckage at the site of the Express’ ditching, the Squadron history suggested that any surviving crewmen may have been captured by the Japanese, or, they were killed by strafing Zeros.

There, the matter seemed to rest.

A search for additional information about the “Grey Geese” and Dogpatch Express yielded a new and rather unexpected account, which appears in the 1996 book 11th Bomb Group (H): The Grey Geese. There, some fifty-three years after the Taroa bombing mission of December 21 1943, veteran Jesse Stay – whose account of the loss of Dogpatch Express appears in MACR 1423 – presented an account of the event that fully and sadly clarifies what happened to the plane and crew.

Mr. Stay’s account – presumably written in the 1990s – is presented below.

It turns out that the plane was initially struck by anti-aircraft fire in the cockpit (oddly, not mentioned in either the MACR or squadron history), to the extent that Lt. Smith was forced to fly, and ditch, the aircraft unassisted. As for the survivors, the impression is given that they were strafed in the water by more than one Zero (again, not mentioned in the MACR or squadron history).

Notably, Mr. Stay wrote that the pilot of the Express, 1 Lt. George W. Smith, was filling in for the crew’s regular pilot, Lt. Thompson, who was wounded over Wake on July 24, 1943. This may explain an aspect of the photo of the Express’ crew, which appears both below, and in the prior blog post: The fact that a member of the plane’s crew – probably having been wounded – is seated in a wheelchair.

Could this man be Lt. Thompson?

THE DOGPATCH EXPRESS AND THE BELLE OF TEXAS

THE DOGPATCH EXPRESS AND THE BELLE OF TEXAS

By Jesse Stay

A mission out of Funafuti is worth remembering. It was on Dec. 20, 1943. We were bombing Maloelap Island in the Marshall group. This was shortly after we had taken Tarawa and the Japanese were able to bomb Tarawa from Maloelap. Our squadron was scheduled to bomb the target in three flights of three planes each. I was leading the second flight. We were to bomb from about 12 thousand feet at approximately noon.

My right wing man was scheduled to be Les Scholar but he became ill and was scratched from the mission. With Les out of the formation, that left only two planes in my flight. The pilot of the second plane, Lt. Charlie Pratte, flying the “Belle of Texas,” also got sick and began to throw up right after take-off. He had a capable co-pilot, however, so they decided to continue the mission.

When we reached Maloelap, the first flight went over the target and dropped their bombs without too much difficulty. We learned later that a 90 mm shell had come up through the open bomb bay doors, through another open door into the back of the airplane and out through the roof of the plane, directly over the heads of the two waist gunners and exploded harmlessly several hundred feet above the plane.

I then led my flight of two planes across the target and we dropped our bombs. As we cleared the target, we were picked up by a dozen or so Zeros so we tried to close up with the first flight for our mutual protection. Our tail gunner then told us that the “Dogpatch Express,” flown by Lt. Smith in the third flight, had been badly hit by anti-aircraft fire and was falling behind the formation. The Zeros were on him like a pack of wolves.

I made a 360 turn with my flight and got in formation with the stricken airplane to try to give him some protection. At the same time, the leader of the first flight, Lt. Warren Sands, made a turn in the other direction and brought his formation up on the other wing of the plane that had been hit.

Apparently an anti-aircraft shell had exploded inside the cockpit, killing the co-pilot and the top turret gunner. There was blood all over the cockpit. Two engines on the right side were out, one of which was on fire. We fought Zeros and tried to encourage Lt. Smith at the same time. His crewmen were throwing out all extra weight in the hopes that the plane could fly on the two left engines. It was too much for the pilot to handle, however, and he finally ditched the plane about 90 miles south of Maloelap.

The plane sand in about 30 seconds. It appeared to us that some of the crew were in the water so we dropped our life rafts as close as we could to the crash site. The other flights had left by this time because of lack of fuel. I stayed around for a few more minutes circling below the clouds at low level, until the Zeros left to return to Maloelap. They were machine gunning the debris from the crash and any survivors. We were trying to discourage this with the few guns we had on our two plans. We were still under attack by the Zeros and there were times on this mission when I could see a hail of tracers coming between my airplane and the “Bell of Texas” on my wing.

Finally Charlie Pratte also had to leave and headed for Tarawa to re-fuel. He had over 300 holes in his airplane but didn’t have one man wounded. On one pass the Japanese machine guns had stitched holes the length of his fuselage and had blown up the oxygen tanks which had knocked down the two waist gunners in time for the machine gun bullets to pass through the fuselage where they had been standing. I later found out that his hydraulic system was also shot out and he landed at the new strip at Tarawa with parachutes tied to the waist and tail guns and which the crewmen deployed as they touched down to slow the airplane because they had no brakes. We had talked about this possibility before but the crew of the “Belle of Texas” received a commendation from General “Hap” Arnold, Chief of Staff of the Army Air Corps for making the first recorded parachute landing. This technique is now used for many of our high speed aircraft and on the space shuttle to slow down on landing.

We called for Dumbo rescue but Smitty and the “Dogpatch Express” were never found. There were no survivors. Lt. Smith was flying on this mission with the crew of Lt. Thompson who had been wounded over Wake Island on July 24, 1943.

Lt. Pratte had his crew were lost on January 22, 1944 on a low level mine laying mission out of Guam over Chichi Jima.

I landed on Tarawa on the old, bomb pocked strip a little later and after taking on 1,000 gallons of fuel from give gallon cans, we took off for Funafuti, a small atoll about six hundred miles to the south. We didn’t want to waste fuel climbing to the south, so we decided to stay below the clouds. For this reason we couldn’t get a fix on the stars and by this time it was dark so that we couldn’t measure our wind drift from the waves below us. We navigated by dead reckoning for what we estimated to be six hundred miles and then started a square search for our little island. On our second right angle turn of our square search we saw some faint lights a few miles away and we were soon back on the ground after being gone for 19 hours with 17 hours in the air. We didn’t have a single hole in our airplane when we examined it after landing.

Reference

May, Bob; Parker, Bud; Gudenschwager, Phil, 11th Bomb Group (H): The Grey Geese, Turner Publishing Company, Paducah, Ky., 1996.

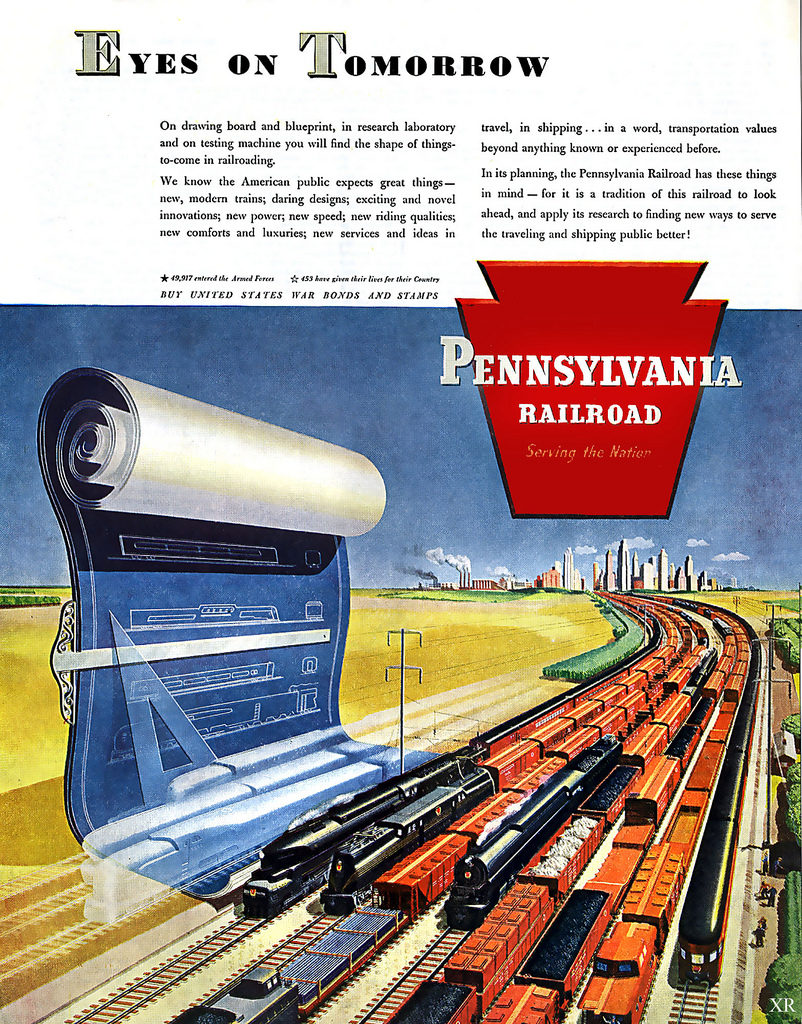

Though “this” example of the advertisement was published in The New York Times, certainly the original advertisement was in color, and probably intended for publication in magazines. Here’s an example of the original ad, from Pinterest:

Though “this” example of the advertisement was published in The New York Times, certainly the original advertisement was in color, and probably intended for publication in magazines. Here’s an example of the original ad, from Pinterest: