Previously, I presented photographs from two Missing Air Crew Reports (MACRs) covering the loss of two 416th Bomb Group A-20 Havoc attack-bombers over France in 1944. That post concluded on an “upbeat” note: The six aviators from both planes safely parachuted and survived the war as POWs, eventually returning to the United States.

The circumstances surrounding “this” post – covering the loss of an 11th Bomb Group (…”Gray Geese”…) B-24 Liberator in the Central Pacific Ocean in late 1943 are, sadly, very different. Though at least some members of the plane’s crew initially survived the ditching of their plane in the Central Pacific, they were never seen again.

In that sense, this Missing Air Crew Report and the two photographs within it epitomize – in a manner far more powerful than words – the nature of the Pacific air war, some seven decades ago.

____________________

The aircraft in question, B-24D 41-24214 (Dogpatch Express) was one of a group of eight B-24s of the 42nd Bomb Squadron, 11th Bomb Group, 7th Air Force, which staged through Nanomea (the northwestern-most atoll in the Polynesian nation of Tuvalu) for a strike against Taroa Island (not to be confused with Tarawa, in the Gilbert Islands!), in the Maloelap Atoll of the Marshall Islands, on December 21, 1943.

Here is a superb photo of Dogpatch Express’ nose art, from Pinterest (via Hawaii.gov):

Here’s another view of the plane (the crewmen are unidentified) appropriately from B-24 Best Web:

Here’s another view of the plane (the crewmen are unidentified) appropriately from B-24 Best Web:

____________________

What happened?

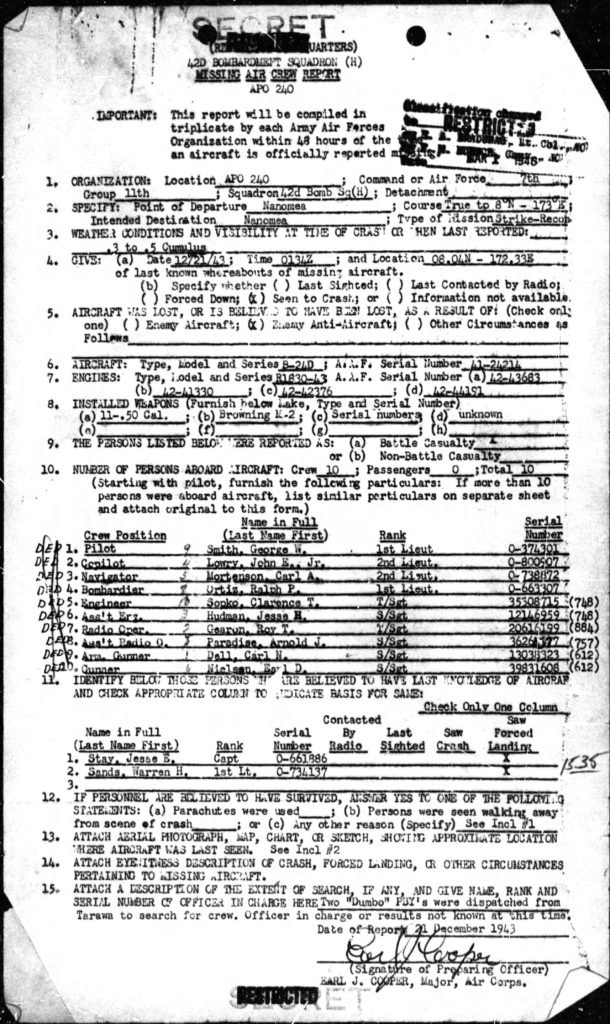

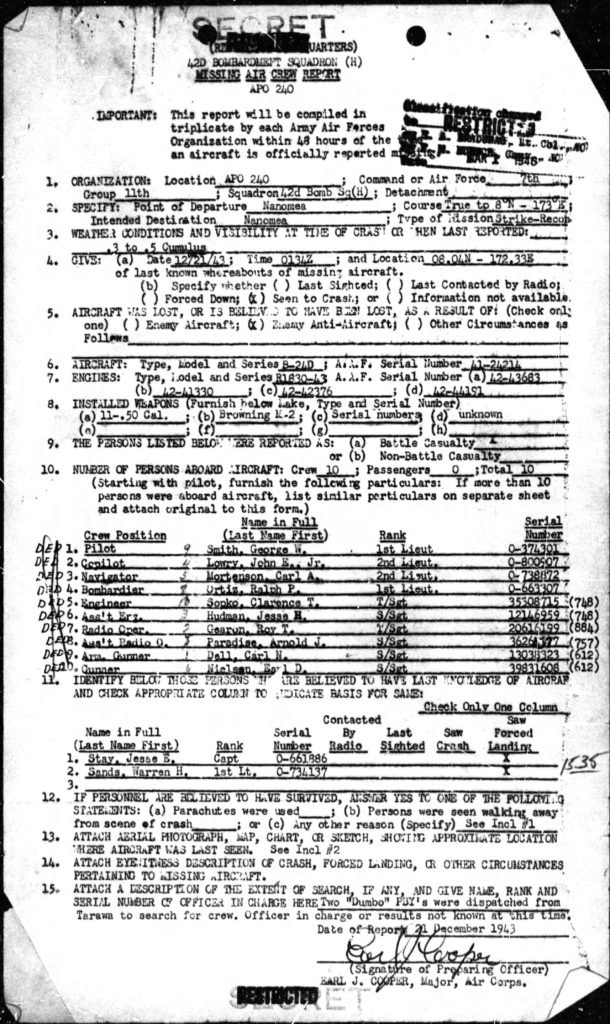

The MACR (# 1423) describes the sequence of events surrounding the loss of the bomber in very great detail, an aspect of MACRs covering 7th Air Force B-24 losses which seems to have been quite consistent.

After the squadron’s bombing run on Taroa, Lt. Smith’s plane was observed to lag behind the other seven bombers, though the specific cause is not delineated in either the MACR or squadron history. Five other B-24s turned back to provide protection for the Express, with one escorting pilot, Captain Jesse Stay (whose account is presented below) maintaining radio contact with Lt. Smith. Having already lost his #4 engine, the Express’ #3 engine soon began emitting smoke, upon which 252nd Kokutai Zeros and Hamps (assigned to the defense of Taroa, as described at Pacific Wrecks) – which had been attacking the formation from the time it left the target – began to especially concentrate their fire upon Smith’s aircraft.

Heavily damaged, with its #4 engine out and #3 engine smoking, Lt. Smith lost altitude, and, eventually ditched.

The Liberator broke in two immediately behind the flight deck, with part of the tail remaining afloat for several minutes. Throughout, three Zeros, which had probably expended their ammunition, remained in the area to observe the scene.

Taken together, the accounts of Captain Stay and Lt. Sands indicate that at least three – and possibly four – of the crew survived both the ditching and a strafing run by a solitary Zero. Two life rafts were deployed, and “water marker” (dye marker?) at the scene was visible from a distance of 10 to 12 miles.

So, at least some of the crew – presumably gunners in the rear of the aircraft – remained alive after the crash.

Later that day, upon the arrival of two PBYs at the location of the ditching (the time of their arrival is not listed and the naval squadron is unidentified) – nothing was found. To quote the squadron history: “It was later found that upon arriving at the spot, no trace was found of the survivors, and it is presumed that they either were strafed by returning Jap airplanes or taken prisoner.”

____________________

The accounts of Captain Stay and Lt. Sands are presented below verbatim, along with a summary of the mission from the records of the 42nd Bomb Squadron:

Captain Stay’s Account

My flight, consisting of myself and Lt. Pratte in A/P #156 followed Capt. Storm’s flight of three airplanes over the target on Taroa Island. We were followed by “C” flight in which Lt. Smith in A/P #214 was No. 2 man. We made our run and turned off to the left, increasing our power and diving to catch up with Capt. Storm’s “A” flight. We had been off of the target approximately 12-15 minutes when S/Sgt. Blackmore, my tail gunner called me to say that one A/P in “C” flight had become a straggler and was being attacked by several Zeros. As he told me this Lt. Sands in A/P #073, who was flying #2 position in “A” flight pulled out of formation and started a turn back. My flight of two ships turned with him and at the same time my Co-pilot informed Capt. Storm of the straggler. Lt. Sands fell in on Lt. Smith’s right wing and I took up a position on his left wing with Lt. Pratte flying on my left wing.

Shortly after this Capt. Storm and his remaining wing man, Lt. Perry in A/P #007 fell into our formation. At this time we noticed that the #4 engine on A/P #214 was feathered and he had many holes in the fuselage and emphennage of his A/P, and he was losing altitude fast. Approximately 3 minutes after we joined him in formation his no. 3 engine caught fire giving off a heavy white smoke.

I spoke to Lt. Smith over V.H.F. and suggested that he feather no. 3 engine and try to put cut the fire with his Lux System. Lt. Smith called back asking me to get Dumbo service for him and I acknowledged. Shortly after Lt. Smith feathered #3 engine and the fire was apparently extinguished. From the time that we had left the target we had been having a running fight with from 15 to 20 Zeros. When Lt. Smith’s #3 engine began to smoke the Zeros began to press their attack and from 7 to 8 overhead passes were made at the formation before Lt. Smith landed his ship in the water. The Zero pilots made excellent use of the sun and they seemed very experienced in this type of attack.

Lt. Smith had been losing altitude rapidly and when he was at about 3,000 ft. he started #3 engine again and it immediately began to smoke again. We dropped down through a .4 cumulus cloud cover and our formation circled through a hole to 1000 ft. to watch his landing. At this time there were still four Zeros in the air but they were apparently out of ammunition because they made no more passes.

Lt. Smith landed in the water at 13:45 L.W.T. at a position of 08 04 N and 172 33 E. The ship broke in two and the nose appeared to go down leaving the trailing edge of the wing and very little of the bomb bay afloat. The whole ship was under water in approximately 3 minutes. We observed at this time one life raft with one man lying prone across it. The rest of the formation left for their base and Lt. Sands, Lt. Pratte and myself circled the scene for cover and to give what aid we could. Three Zeros were still in the area but appeared to be only observing the crash. Our top gunner was only able to fire a few shots at any of them.

Lt. Sands dove in low over the raft and dropped a life raft then we dove in and dropped a box of emergency rations. Both the raft and the rations remained intact and afloat. We called for Life Guard service on command voice on 6210 K.C. giving our distance of 90 miles and our course of 120° M from the target.

The Zeros left and we climbed above the clouds and Lt. Pulliam took a sun shot over the raft and confirmed our position. At the same time my radio operator was calling first Tarawa, then Makin, then Apamama but receiving no answer from any of them he again called Tarawa and sent through a request for Dumbo Service. Our three planes left the scene for Tarawa and after we had been on course for approximately 10 minutes the men in the back of my A/P reported seeing what they thought was a submarine wake behind us. I turned around and headed back to the raft hoping to be able to assist the Submarine but on approaching the life raft we were able to see the water marker for from 10 to 12 miles from 1000 ft.

As we dove over the scene to fifty feet we saw that there were two rafts inflated and three men ware in one and possibly one on the other. We set our liaison up to transmit on 6210 and called for Life Guard Service again. We left the scene finally at 1434 L.W.T. and landed at Tarawa to refuel where we learned that two PBYs had been sent out 2 hours before.

Captain Jesse E. Stay

Lt. Sands’ Account

I was flying A/P # 073 in the Number 3 position of “A” Flight. We had left the target about five minutes when the tail gunner called and said there was a B-24 smoking and losing altitude and was alone. I told my crew that we were going to make a 90° turn so I could get a look at it. When I observed the conditions under which Lt. Smith was placed I continued my turn and went back to get in formation with him. We pulled in on his right wing as that was the side that about 10 Zekes were making overhead passes at the crippled plane. We had been in formation with Lt. Smith about three or four minutes when the four other planes pulled into formation on his left wing. We continued to escort him until he landed in the water at about 13:45 L.W.T.

The plane appeared to break in two just back of the flight deck. The entire plane with the exception of the tail surfaces sank almost immediately. The tail surfaces floated for about four minutes. One man was definitely seen to be laying across a partly inflated, overturned life-raft with possibly one other person in the water. I ordered my crew to get a life raft ready to throw overboard which was done as we passed over at a minimum altitude.

One Zeke was seen to make a strafing attack at the spot where the plane sank. The Zeke then left the area. We circled for another ten minutes, and seeing no more Zekes, we departed for Tarawa. My radio operator immediately sent out a position report of the crashed plane which was unanswered.

1 Lt. Warren H. Sands

42nd Bomb Squadron History

TAROA MISSION * 20 December 1943

Lt. Kerr in 143, Captain Storm in 155, Lt. Gall in 100, Lt. Perr (431st) in 007, Lt. Schmidt in 838m Lt. Stay in 960, Lt. Sands in 073, Lt. Smith in 214, and Lt. Pratte in 156, staged through Nonomea for a strike against Taroa on Maloelap Atoll. Each airplane carried 6 x 500 GO bombs. Interception began as the airplanes pulled away from an AA spattered bomb run, with 20 – 30 Zekes and Hamps rising to the attack.

AA began as the airplanes neared the island, in some cases not reported as occurring until the run had started, with a majority of the bombs landing in or near the target area. Lt. Gall did not reach the target due to malfunction. It was on this mission that Lt. Smith had two engines shot out either by AA or cannon fire, and found it necessary to make a water landing about 75 miles from Taroa. Covered by other elements of the flight, he made what was described as “an excellent” water landing, from which at least four men were seen to leave the badly damaged airplane and crawl onto two rafts. Captain Stay had, prior to the crash, radioed to both Dumbo and Lifeguard to come in, and this was later found to have reached both agencies through other intercepting mediums as well as the original call. It was later found that upon arriving at the spot, no trace was found of the survivors, and it is presumed that they either were strafed by returning Jap airplanes or taken prisoner.

Several Jap interceptors were knocked off on this mission, by Sergeant Kernyat of Sands crew, Sgt. Brannan of Lt. Kerr’s, Sgt. Roth, Sgt. Ball, and S/Sgt. Tanner of Captains Stay’s crew. They were all confirmed…

____________________

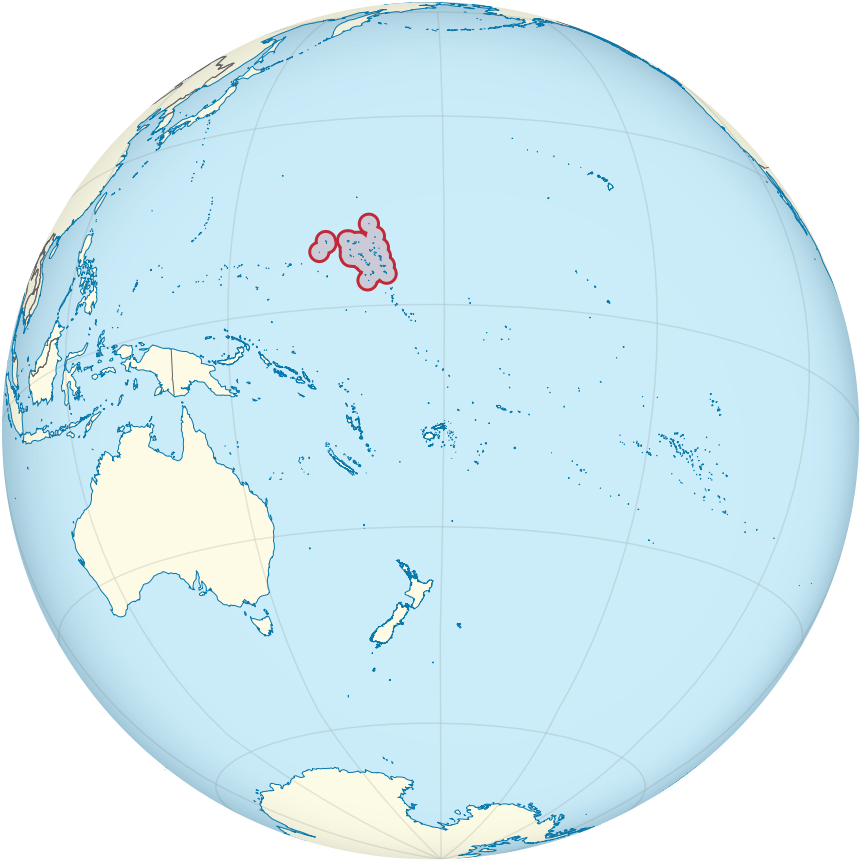

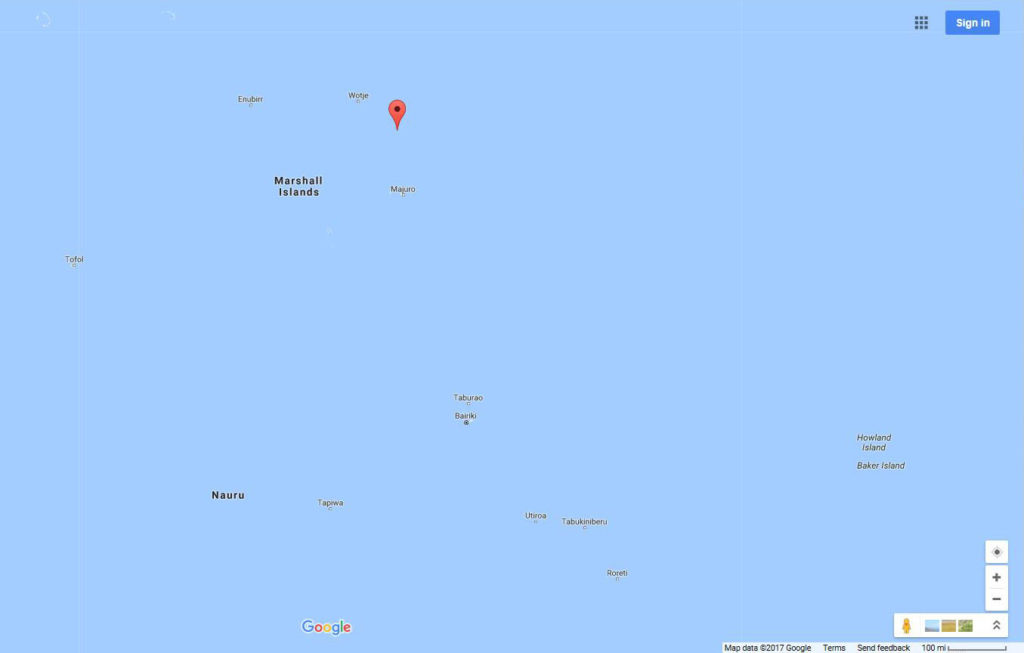

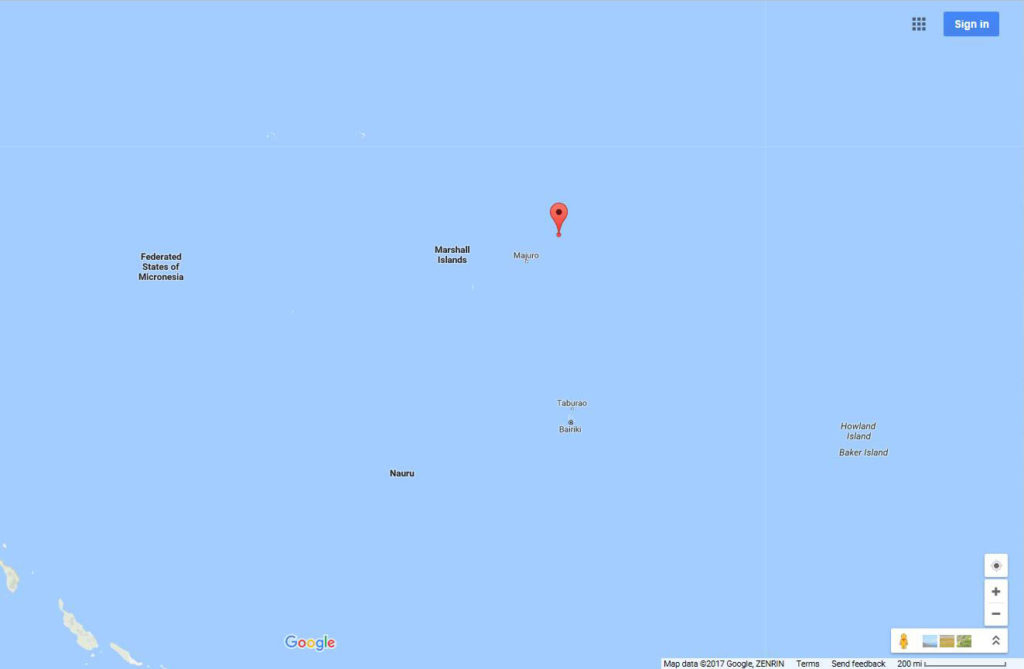

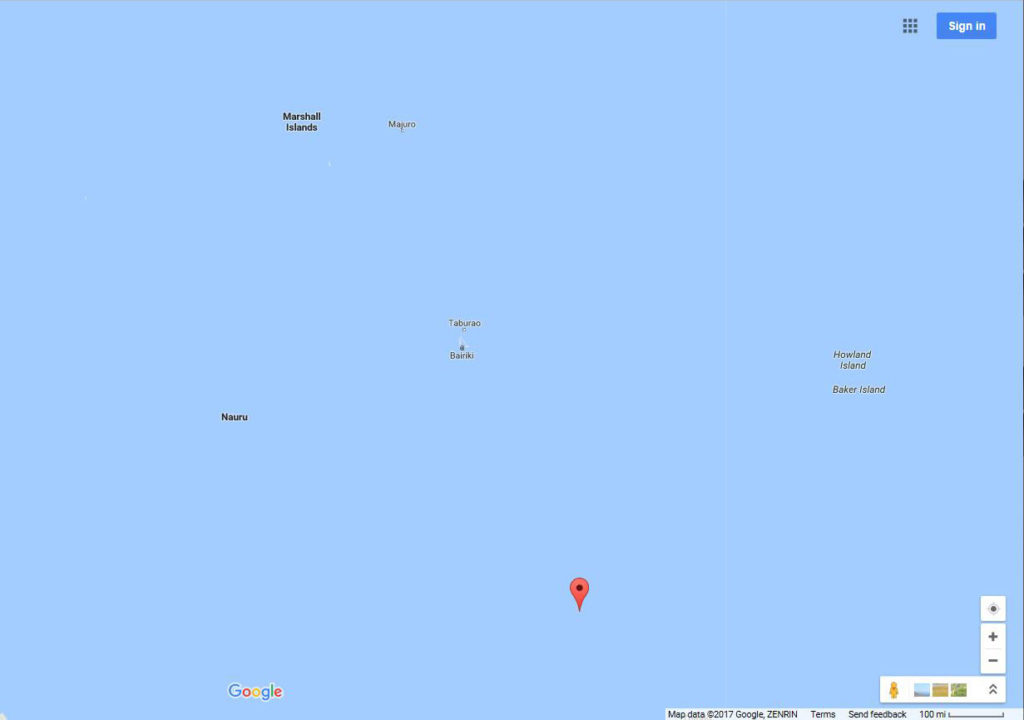

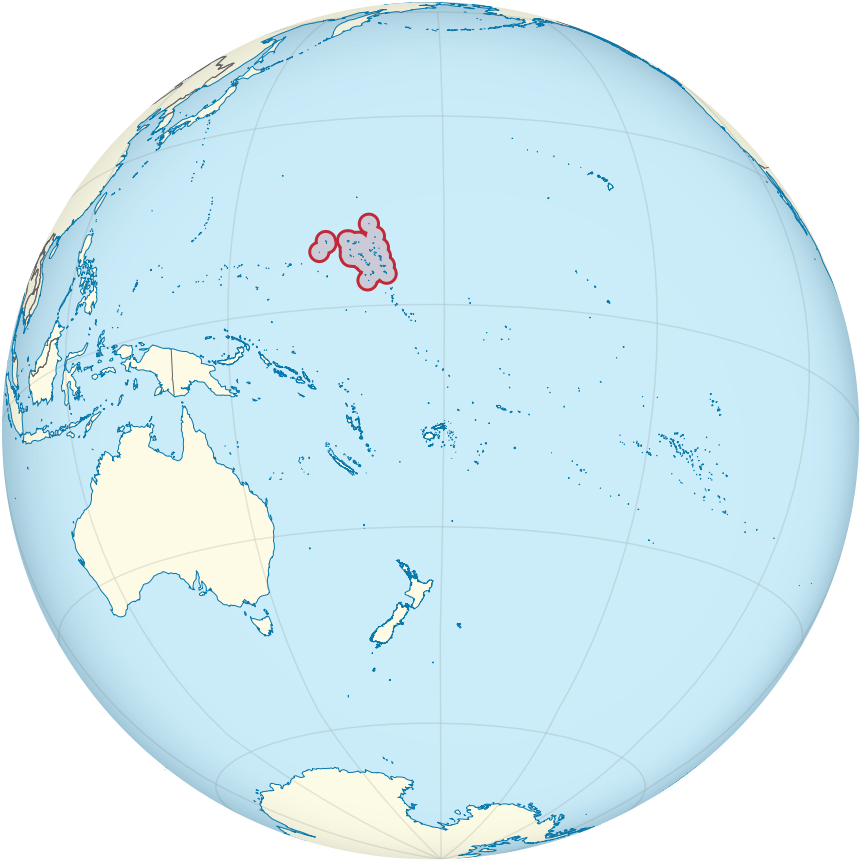

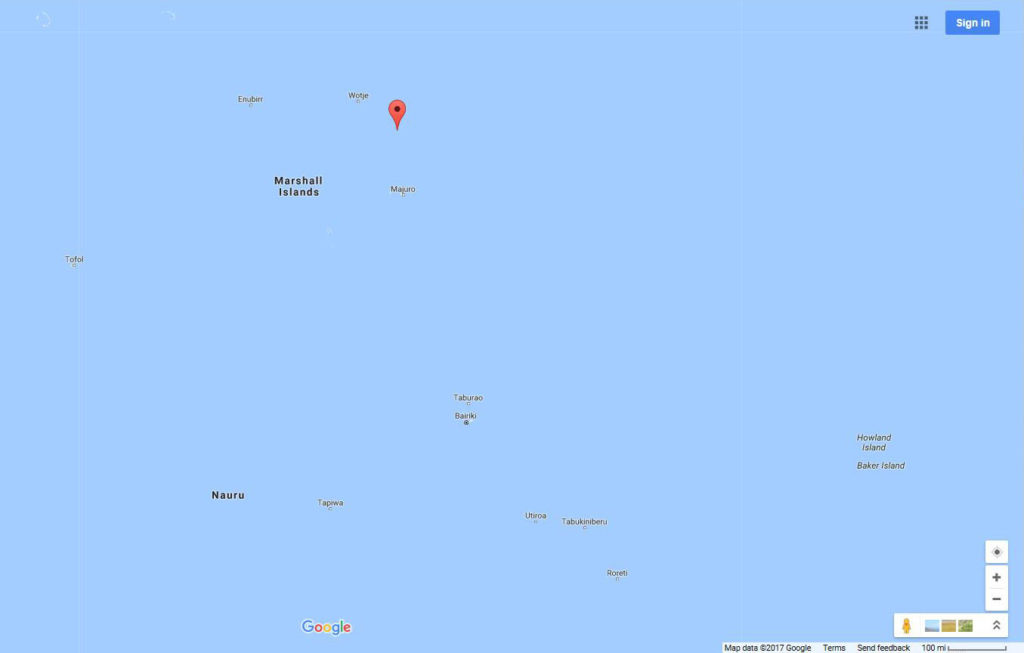

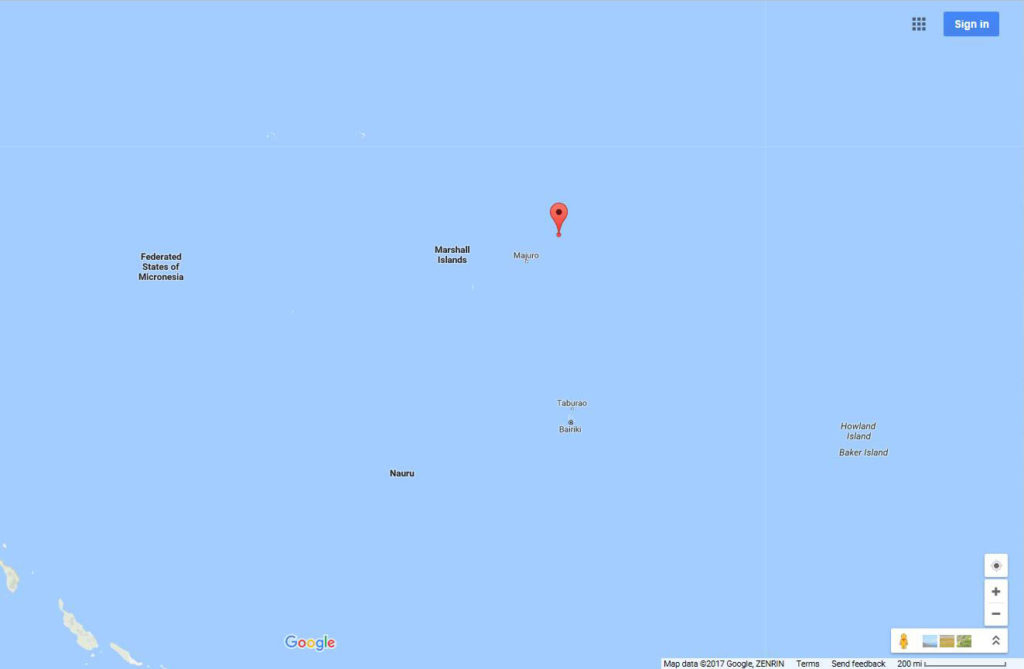

To give you a better understanding of the setting and location of this incident, the following series of maps and illustrations show the location of the Marshall Islands in general and Taroa in particular, the island’s appearance in 1943 (and 2017), as well as the location where Dogpatch Express was lost in relation to surrounding islands.

____________________

Here is a map of the Marshall Islands (from Wikimedia Commons) illustrated on a global view of the earth, centered on Polynesia.

____________________

____________________

The map below, from the Diercke International Atlas, shows Taroa Island (right center) and the other islands comprising the Maloelap Atoll.

____________________

____________________

This undated Air Force photograph shows the “Bombing of the Japanese Airfield on Taroa Islet [sic]…” The image is from the WW II U.S. Air Force Photo Collection at Fold3.com. (Image A42044 / 73717 AC)

____________________

____________________

Here’s a Google Earth satellite view of Taroa, circa 2017. The island’s miniscule size is evident by the distance scale (one thousand feet!) in the lower right corner of the image. Note the changes in the island’s shape that have ensued since World War Two, and, the still-visible remnant of one of the two runways.

____________________

____________________

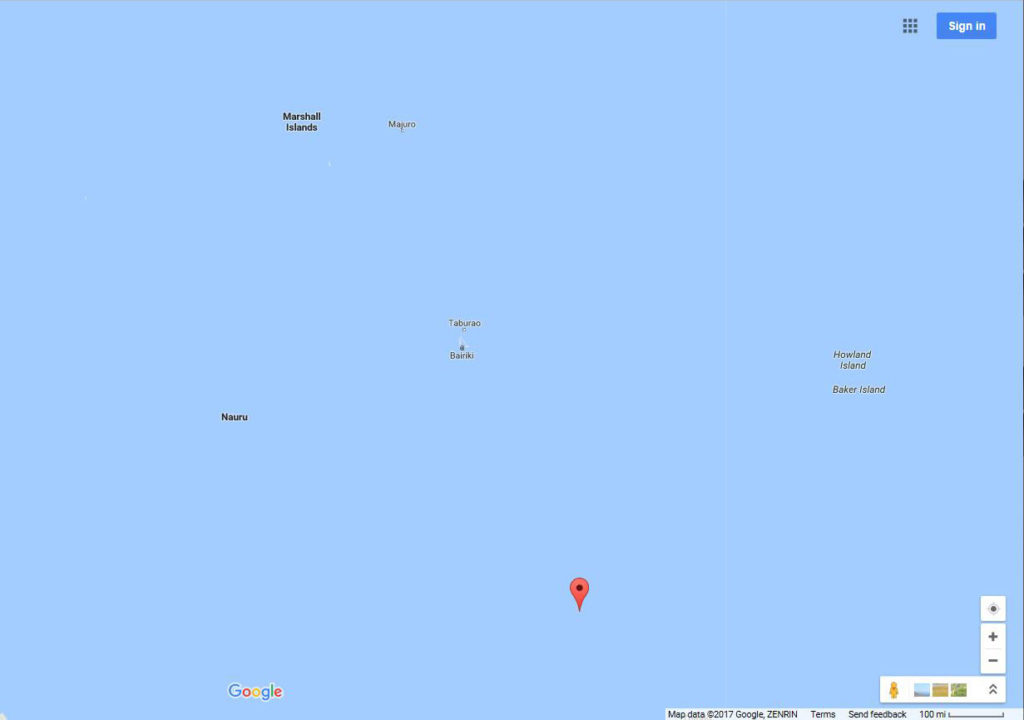

This Google map shows the location of Taroa (via the red pointer), relative to surrounding islands. Obvious (in reality, not-so-obvious) is the fact that the Maloelap Atoll and Taroa are “invisible” at the scale of this map.

____________________

____________________

This map, generated by entering latitude and longitude coordinates in Google Earth, shows the location where Dogpatch Express was ditched (denoted by the red pointer). Akin to above, at this scale, Maloelap and Taroa do not appear.

____________________

____________________

This map shows the location of Nanomea Island (red pointer once more) relative to the Marshalls. Akin to the above map views, Nanomea is so small as to be “invisible”

____________________

____________________

The plane was lost.

Ten men were lost.

Who were they?

Typical for MACRs, Report 1423 gives the names of the plane’s crewmen, their crew positions, and, their serial numbers. However, the Report does not contain any “contact” information; the names and residential address of next-of-kin. If you were to go by the MACR alone, the men would be, in a sense, “anonymous”: names, ranks, serial numbers, and nothing more.

However, there is one set of records in the National Archives that gives these men fuller identities.

However, there is one set of records in the National Archives that gives these men fuller identities.

This information is present in Records Group 165, in the “Bureau of Public Relations Press Branch” releases covering military casualties (specifically Missing in Action, Killed in Action, Wounded in Action), which were issued throughout the war to the news media by the War Department.

Within these press releases, casualties are listed by theater of war (Europe, Mediterranean, Pacific, etc.), with mens’ names listed alphabetically within each category. The name of a casualty was usually (usually) released approximately one month subsequent to the calendar date on which he was killed, wounded, or missing. The predictably of this time-frame is a very reliable way (at least, through the late spring of 1944) to identify the year and month when the press release listing a serviceman’s name, his next-of-kin, and emergency address, was released to the news media.

(Maybe more about this in a future post?)

Given that Lt. Smith’s crew was lost in late December of 1943, it was assumed that their names could be found in Press releases issued in late January of 1944. Research in RG 165 verified this: The men’s names appeared in Casualty Lists issued on January 21, 22, and 24, and (one man) February 9, of 1944.

____________________

The crew’s names are other relevant information are presented below, along with (in parenthesis) the calendar date of the relevant Press release.

They were:

Pilot Smith, George W. 1 Lt. 0-374301 (1/22/44)

Mrs. Ida R. Smith (mother), Prairieton, In.

Co-Pilot Lowry, John E., Jr. 2 Lt. 0-800907 (1/21/44)

Mrs. Margaret E. Lowry, Jr. (wife), Spring St., Smyrna, Ga.

Navigator Mortenson, Carl A. 2 Lt. 0-738872 (1/22/44)

Mr. Harry Walter Mortenson (brother), 1380 Riverside Drive, Lakewood, Oh.

Bombardier Ortiz, Ralph P. 1 Lt. 0-663307 (1/22/44)

Mr. Daniel C. Ortiz (father), 603 Agua Fria, Santa Fe, N.M.

Flight Engineer Sopko, Clarence T. T/Sgt. 35308715 1/22/20 (1/22/44)

Mrs. Mary S. Sopko (mother), 2138 West 26th St., Cleveland, Oh.

Memorial Tombstone – at Ohio Western Reserve National Cemetery – Section M, Plot 6 (Photo by Douglas King)

Radio Operator Gearon, Roy T. T/Sgt. 20616199 (1/21/44)

Mrs. Catherine Ann Gearon (mother), 5464 Woodlawn, Chicago, Il.

Crew Picture and related information from Patrick Maher (Second Cousin) (See below.)

Gunner Hudman, Jesse Harvey S/Sgt. 12146959 1918 (1/21/44)

Mrs. Florence L. Hudman (wife), 10 Marble Place, Ossining, N.Y.

Mrs. Carrie Hudman (mother), Gilbert Park, N.Y.

Memorial Tombstone – at Dale Cemetery, Ossining, N.Y. (photo by Jean Sutherland)

Notices about Sgt. Hudman appeared in the Citizen-Register, of Ossining, N.Y., on May 22 and 25, 1946, concerning a memorial service that was held in his behalf on May 19 of that year.

Gunner Paradise, Arnold J. S/Sgt. 36264577 (1/21/44)

Gunner Paradise, Arnold J. S/Sgt. 36264577 (1/21/44)

Mrs. Fern Paradise (mother), Garden Acres, Chippewa Falls, Wi.

WW II Memorial – June Havel (sister)

Gunner Dell, Carl N. S/Sgt. 13038323 4/19/20 (2/9/44)

Mr. William J. Dell (father), Route 1, Middle Road, Pittsburgh, Pa.

Memorial Tombstone at Saint Mary’s Cemetery, Pittsburgh, Pa. (Photo by “Genealogy-Detective”)

Gunner Nielsen, Earl Dewayne S/Sgt. 39831608 7/29/21 (1/21/44)

Mrs. Vera P. Nielsen (mother), Cleveland, Id.

Memorial Tombstone at Cleveland Cemetery, Franklin County, Id. (Photo by Bill E. Doman)

All the crewmen are memorialized in the Courts of the Missing (Court 7), at the Honolulu Memorial, in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, at Honolulu, Hawaii.

Remarkably, there is a photograph of this crew…

Mr. Patrick Maher, a second cousin of T/Sgt. Roy Gearon, has posted a picture of the crew at the Memorial Page for his relative at FindAGrave.com, with the message, “We are 2nd cousins Roy. Know you were remembered then and still by your family with a proud military tradition. May you and your crew forever rest in peace at the bottom of the ocean. Your last mission was accomplished Sir. Sorry on behalf of your government for your case and many like it. Your death date was December 21, 1943 not 1946. Silver Star recipient. Rest in Peace Sir.”

Mr. Maher’s entry also includes a close-up image of the final moments of Dogpatch Express, identical to one of the photographs in the MACR below.

Mr. Maher’s entry also includes a close-up image of the final moments of Dogpatch Express, identical to one of the photographs in the MACR below.

____________________

The photos?

Unlike the images for the A-20s, these two photos are unattached to the documents in the MACR; they’re “loose” in the file. Here they are:

____________________

____________________

Here’s the “first” image. This shows Dogpatch Express heading back – well, trying to head back – to Nanomea, showing Lt. Sand’s B-24 to the right and slightly above Lt. Smith’s aircraft. This may be the point at which – as described by Capt. Stay – the squadron dropped to an altitude of 3,000 feet, upon which the Express’ #3 engine emitted smoke when it was restarted.

____________________

____________________

This is a 2,400 dpi crop of the above photo. The damage to Dogpatch Express is obvious. The #4 engine has been feathered, and there’s a large hole in the starboard rudder. Close examination shows that the ball turret has been rotated downwards and retracted into the fuselage, while in the dorsal turret – rotated to the rear – the guns have been elevated to 70-80 degrees. The trail of smoke – thick smoke; dense smoke; white smoke – emitted from the #3 engine is plainly evident.

Given that the direction of flight from Taroa to Nanomea was approximately south-southeast, by looking “into” this image – the viewer is looking west-southwest.

Beyond and below the aircraft, and into the indefinite horizon, there are clouds, water, and, more clouds and more water.

____________________

____________________

This picture shows the scene of Dogpatch Express’ ditching.

(Though this post doesn’t pertain to camouflage and markings, this image illustrates the Insignia Blue overpaint of the Insignia Red surround to the National Insignia, which had been a feature of the national insignia of American military aircraft between 28 June and 14 August 1943.)

Though intended as a historical record – for which it more than serves its purpose – this photograph – like the image above – is extremely evocative of the war over the Pacific: Distance. Water. Emptiness.

The point of the B-24’s impact – a trail of churned water perhaps several hundred feet long – is obvious. However, compared with the expanse of sea encompassed by the image and receding into the distance, the site is miniscule.

____________________

____________________

This is a 2,400 dpi crop of the above image. Though the resolution is too low to identify details, four objects can be seen floating at the top of the “ditching trail”. Captain Stay mentioned that the scene was visible up to 12 miles away, due to dye marker in the water. Is the gray patch of water in the upper left of the ditching site the dye marker?

____________________

____________________

The survivors – whoever they were – were never seen again.

The 42nd Bomb Squadron mission summary suggests two possibilities for their fate: They were strafed by Zero fighters during the interval between the departure of the other B-24s and the arrival of PBYs, or, they were captured by the Japanese, via naval vessels.

Given the location and circumstances under which the crew was lost, and, the passage of time, what ultimately happened to the few survivors will probably forever be unknown. There is a slight – (very slight?) – possibility that IDPFs filed for the crew may include more definitive information about their fate, but even those documents, I suppose, will be ambiguous as well.

What is not supposition was – and will always be – their bravery, and the bravery of many men like them.

____________________

A Brief Digression on Names and Numbers

Did the Army Air Force (or post-1947, the Air Force) ever complete statistical studies comparing the chances of survival for WW II USAAF bomber aircrews lost over the Pacific, to those for aviators lost in the European / Mediterranean Theatres of War? I don’t know!

I’ve attempted a brief comparison of that sort. Or, at least half of a comparison… This was based on an evaluation of statistics about 7th Air Force B-24 losses, with information derived from MACRs (my own review of those documents, extending over some years), and, miscellaneous references.

MACRs and other sources for losses of 7th Air Force B-24s (75 aircraft covered by “wartime” MACRs, 6 aircraft covered by post-war “fill-in” MACRs, and 11 B-24 losses mentioned by books and other sources) cover a total of 92 aircraft. (Doubtless there were other planes for which MACRs were never filed…)

Among those 92 B-24s, there was a total of 950 airmen, of whom there were 237 survivors and 713 fatalities. The 237 survivors represent 24% of the 950 crewmen. (There were no survivors from 51 planes, while entire crews survived among 5 of the 92 lost aircraft.)

In light of these statistics, and bearing in mind that these figures represent people, not simply “numbers” – I wonder if…it seems that…despite the greater aircraft losses incurred by the 8th and 15th Air Forces, as opposed to the 7th (and 13th, and 5th)…the chances of survival for an aircrew lost in the Pacific Theater of war were actually far lower than in Europe and the Mediterranean.

If so, I’d attribute this to the utterly different geography encompassed by and overflown in the Pacific, where combat missions by nature occurred over vast, near-featureless expanses of water; abruptly changing climatic conditions; the challenges inherent to locating downed airmen at sea, during both aerial and sea-borne searches; the lower chances of simple physical survival (aside from enemy activity) for those few aviators who may have been able to parachute onto land or sea; and last – but hardly insignificantly – the ethos of the Japanese regarding captured members of the Allied Air Forces. (Thirteen 7th Air Force B-24 crewmen survived the war as POWs of the Japanese.*)

So, to conclude (if there is a conclusion) let these photos stand as a reminder of those who didn’t return, and the very few who did.

____________________

Notes

For an essay on Taroa illustrated with stunningly beautiful contemporary photographs, visit The World War II Legacy of Taroa Island.

For a historical overview of Taroa, specifically focusing on the island during World War II and as a tourist destination (circa 1995), see the essay Dirk H.R. Spennemann (of the Institute of Land, Water and Society, at Charles Stuart University), at Taroa, Maloelap Atoll – A brief virtual tour through a Japanese airbase in the Marshall Islands.

* These POWs were:

ABEL, WILLIAM E. S/Sgt. 36440823 Gunner (Tail)

CARTWRIGHT, THOMAS C. 2 Lt. 0-831661 Pilot

EIFLER, HAROLD 2 Lt. 0-721673 Pilot

GARRETT, FRED F 1 Lt. 0-740163 Pilot

HRYSKANICH, PETER 2 Lt. 0-806683 Co-Pilot

MARTIN, WILLIAM R., JR 2 Lt. 0-2065804 Navigator

MINIERRE, LINCOLN S. T/Sgt. 11073217 Radio Operator

PHILLIPS, RUSSELL A. Capt. 0-726463 Pilot

SELLERS, CLYDE J. Sgt. 36871713 Gunner

SMITH, RICHARD M. 2 Lt. 0-692346 Navigator

STODDARD, LOREN A. Capt. 0-428873 Pilot

WALKER, ARTHUR JAMES Col. 0-022462 Pilot

ZAMPERINI, LOUIS S. 1 Lt. 0-663341 Bombardier

____________________

References

(Books)

Bell, Dana, Air Force Colors Volume 2 – ETO & MTO 1942-45, Squadron/Signal Publications, Carrollton, Tx., 1980.

Cleveland, W.M., Grey Geese Calling – Pacific Air War History of the 11th Bombardment Group (H) 1940-1945, 11th Bombardment Group Association Inc., Seffner, Fl., 1992.

Doll, Thomas E., Jackson, Berkley R., and Riley, William A., Navy Air Colors – United States Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard Aircraft Camouflage and Markings, Vol. 1 – 1911-1945, Squadron/Signal Publications, Carrollton, Tx., 1983.

Forman, Wallace R., B-24 Nose Art Name Directory, Specialty Press Publishers and Wholesalers, North Branch, Mn., 1996.

Rust, Kenn C., Seventh Air Force Story …In World War II, Historical Aviation Album, Temple City, Ca., 1979.

(Web Sites)

11th Bombardment Group History, at http://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/browse?type=subject&value=11th%20Bombardment%20Group%20(H)

At OAKTrust Digital Repository of Texas A&M University – Special Collections

http://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/

In connection with / related to biography of T/Sgt. Paul Fredrick Adler

42nd Bombardment Squadron (Heavy). Monthly Squadron Histories and Documents, 20 May 1943 – 5 March 1944

http://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/bitstream/handle/1969.1/90568/3%20History-42dBS-1943-44-Missions.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (On pages 89 of 104 of PDF.)

Dogpatch Express nose-art (Pinterest), at https://www.pinterest.com/pin/551268810615004024/

Dogpatch Express crew photo (B-24 Best Web), at http://www.b24bestweb.com/dogpatchexpress-v1

Dogpatch Express nose-art (B-24 Best Web), at http://www.b24bestweb.com/dogpatchexpress-v1-1.htm

Dogpatch Express nose-art (B-24 Best Web), at http://www.b24bestweb.com/dogpatchexpress-v1-2.htm

Marshall Islands (at Wikimedia Commons), at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marshall_Islands.

Nanomea Island (Wikipedia entry – listed as “Nanumea”), at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nanumea

Taroa Island (at Pacific Wrecks Database), at http://www.pacificwrecks.com/airfields/marshalls/taroa/index.html

Taroa Island (at Charles Stuart University), at http://marshall.csu.edu.au/Marshalls/html/japanese/Taroa/Taroa.html

The World War II Legacy of Taroa Island (at Nothing Unknown), at https://www.nothingunknown.com/content/2016/10/7/taroa-island

(United States National Archives)

Records Group 165 “War Department Special Staff Public Relations Division News Branch Press and Radio News Releases, 1921-1947” (arranged chronologically), at Stack Area 390, Row 40, Compartment 3, Shelf 6.

THE DOGPATCH EXPRESS AND THE BELLE OF TEXAS

THE DOGPATCH EXPRESS AND THE BELLE OF TEXAS