Nearly seventy-six years ago – on Wednesday, November 3, 1943 – an officer of the 823rd Bomb Squadron of the 38th “Sunsetter” Bomb Group made entries in his squadron’s historical records concerning that day’s central event: A strike mission along the New Guinea coast from Alexishafen to Bogadjim, to attack barges, buildings, and concealed enemy troops.

The outcome of the mission was reported as follows:

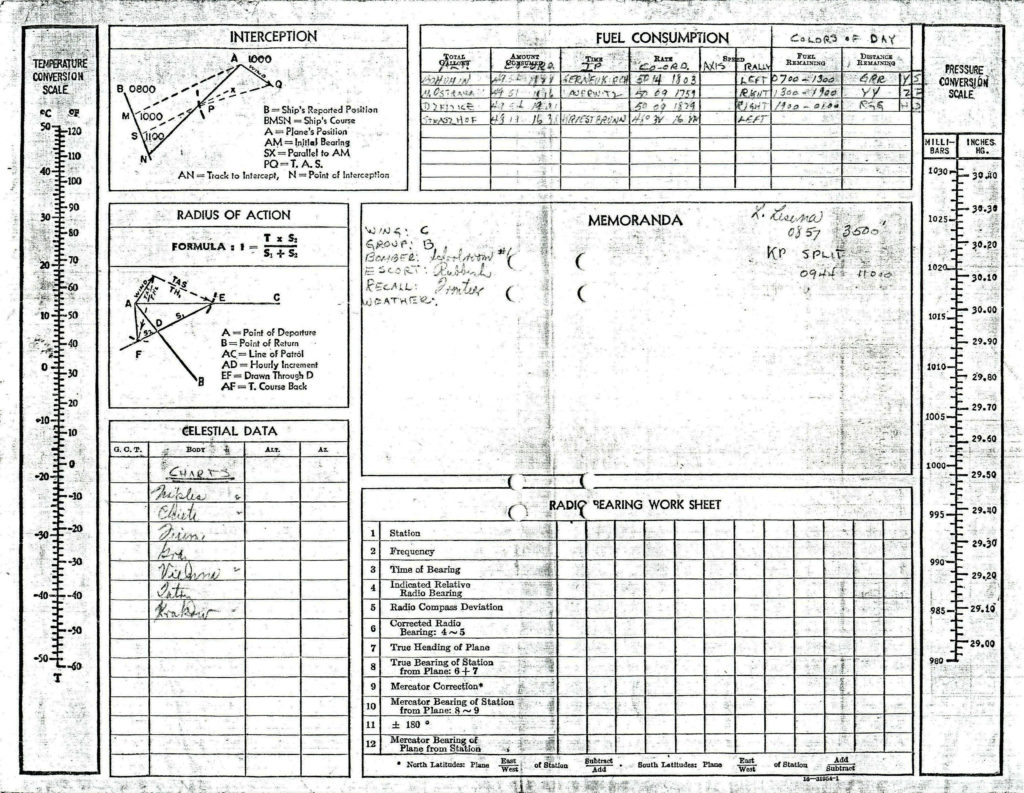

Our pilots and crews took off again to slap the little Jap off the map. Nine B-25Gs took off at 0713L to blast out barges, possible large hideouts and buildings from Alexishafen south of Bogadjim, New Guinea. Fighter cover was effected over Nadzab at an altitude of 3500 feet. The fighter escort consisted of P-47s. The flights were of three planes each and were led by the flights of the 822nd Squadron. 28 x 500 lb. 4-5 second delay demolition bombs were dropped in specific targets. Many of the bombs scored direct hits on barges along the coast. 1 bomb dropped safe due to rack failure and 3 bombs were returned to base due to mechanical failure. 82 rounds of 75mm were fired on runs with a number scoring hits and the remainder with no visible results. Villages and hideouts were thoroughly strafed with 6100 x .50 calibre and 1300 x .30 calibre ammunition. Photos were taken of the strike.

Next followed remarks covering events experienced by specific aircraft and crews, focusing on battle damage, and, the loss of B-25G 42-64850:

The ack-ack encountered was moderate inaccurate and heavy coming from Madang, Alexishafen and Erimhafen Plantation. Plane no. 769, piloted by Remshaw, received a hole in the bomb bay door from fragment of 20mm. Plane No. 874, piloted by Shulich, received large hole in left vertical stabilizer from undetermined type of shell. Plane No. 850, the crew of which were Smith F/O pilot, Newland O.T. co-pilot, Chapin R.D. navigator, Anagos T. radio man, Boykin J.R. gunner crashed in water between Bili Bili Island and mainland. Cause unknown but thought due to loss of power due to damage from ack-ack. All five crew members last seen in life raft, apparently uninjured, rowing toward Bili Bili Island.

Throughout the attack no interception was encountered. The remaining eight planes landed at Durand at 1135/L.

The next day – November 4 – no combat missions were flown by the 823rd Bomb Squadron. This brief pause in operations gave the squadron historian time to ponder the fate of the missing crew, his brief notes encompassing the hope for their rescue against their more likely fate as captives of the Japanese. Specifically:

All crew members express deep sorrow for the five crew members who were last seen in a life raft heading toward Bili Bili Island. What will become of them no one knows. Let’s hope that they are safe.

Alas, they were not safe.

They would never return.

Today, the five crew members of B-25G #850 – Smith, Newland, Chapin, Anagos, and Boykin – remain among the over 73,000 American servicemen still missing from the Second World War. Barring a fortuitous archival or archeological discovery, they will probably ever remain as such: “Missing in Action”.

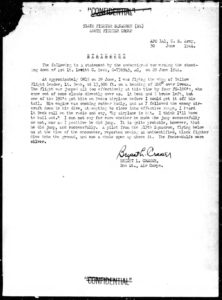

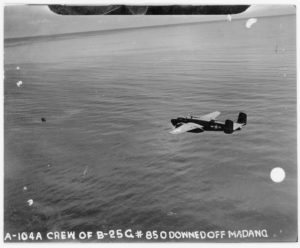

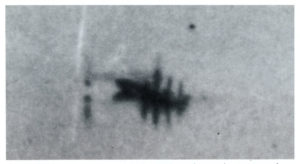

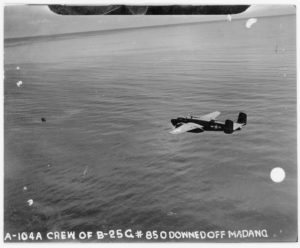

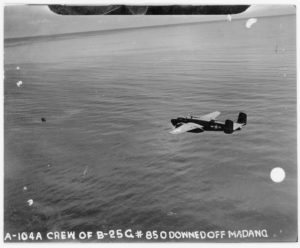

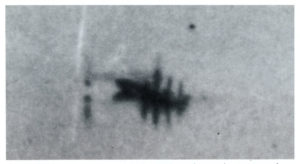

But, the historical record of this crew’s loss is singularly different from the overwhelming majority of accounts of Allied World War Two aviators lost in either the Pacific or European Theaters of War. This is because the Missing Air Crew Report covering the crew’s loss – MACR 1087, to be specific – includes a photograph of the crew (albeit, as viewed from a distance) as last seen by fellow members of the 823rd Bomb Squadron en route back to the 38th Bomb Group’s base at Port Moresby.

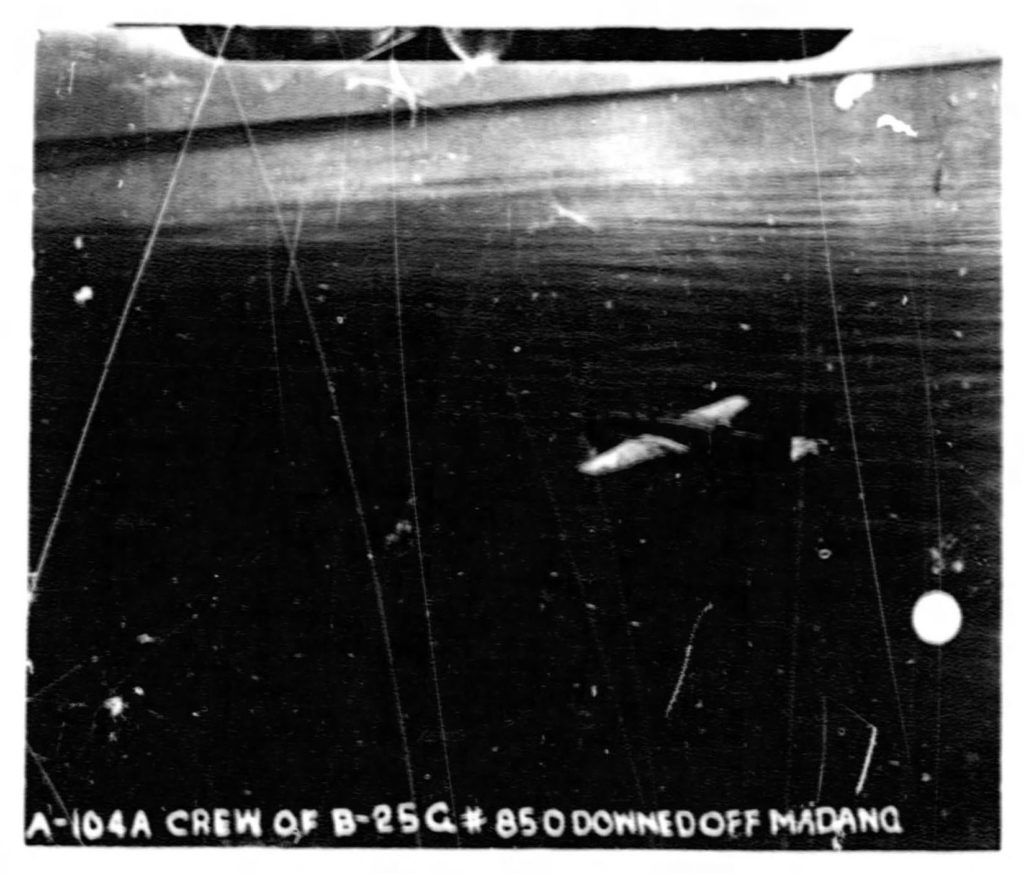

The photograph was first discovered as I was reviewing MACRs via Fold3.com, which database / website many readers of this post are probably well familiar. The Fold3 version of this image is shown below:

In August of 2014, I had the rare opportunity, during a visit to the National Archives in College Park, of viewing and digitizing the original (?) “physical” (!) MACR and the included photograph (see “The Missing Photos”).

So, here is the above image, as copied via an EpsonPerfection V600 scanner.

______________________________

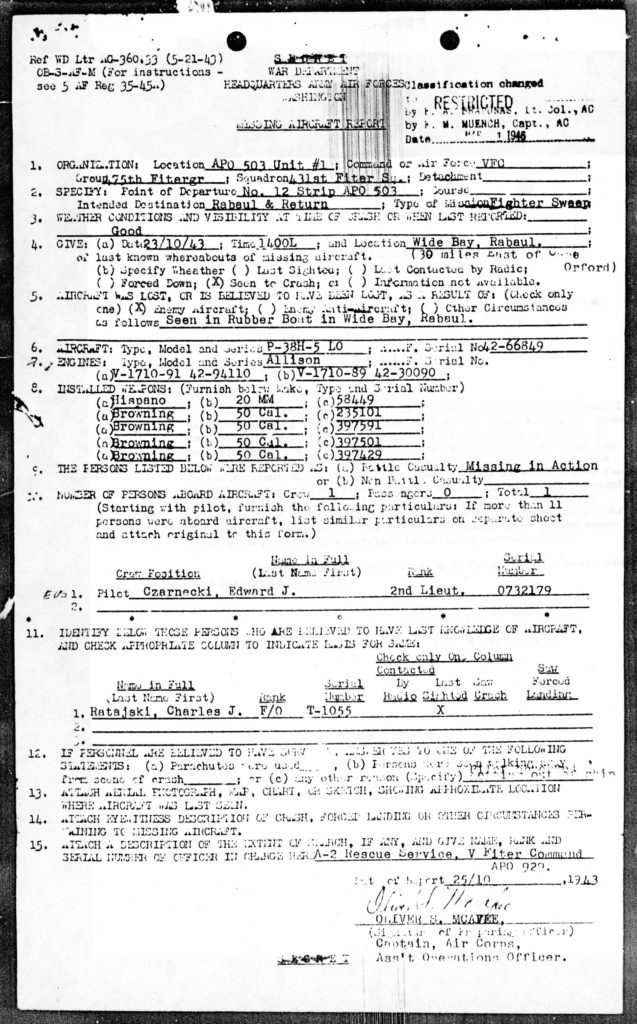

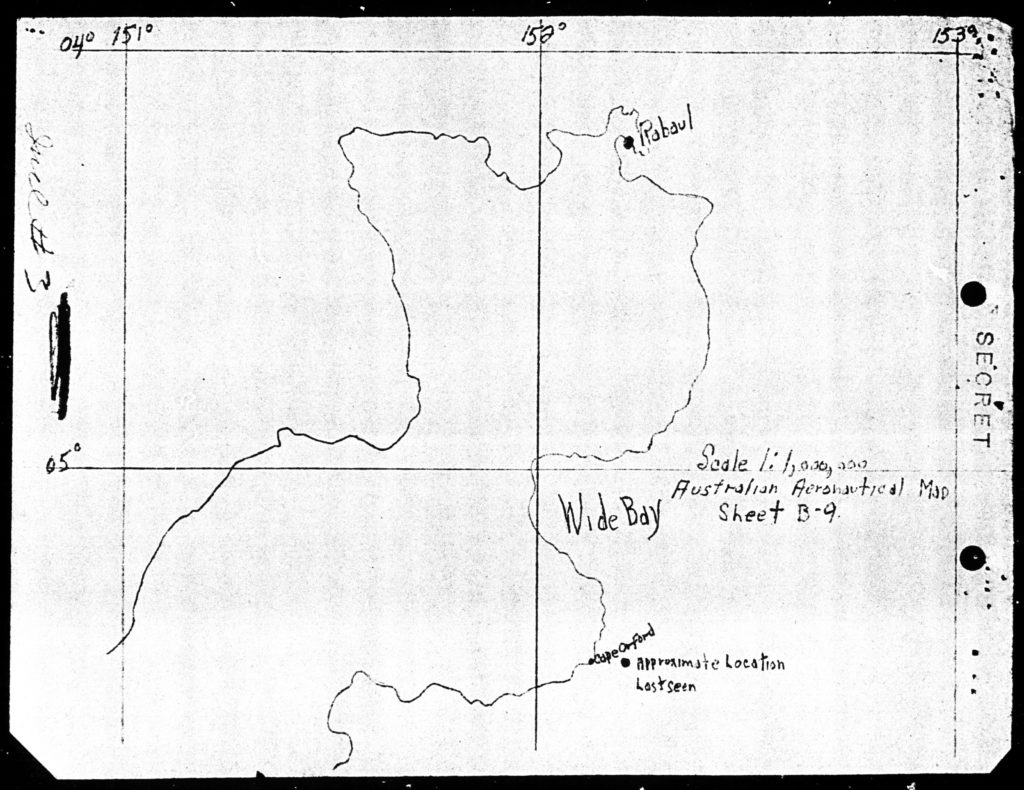

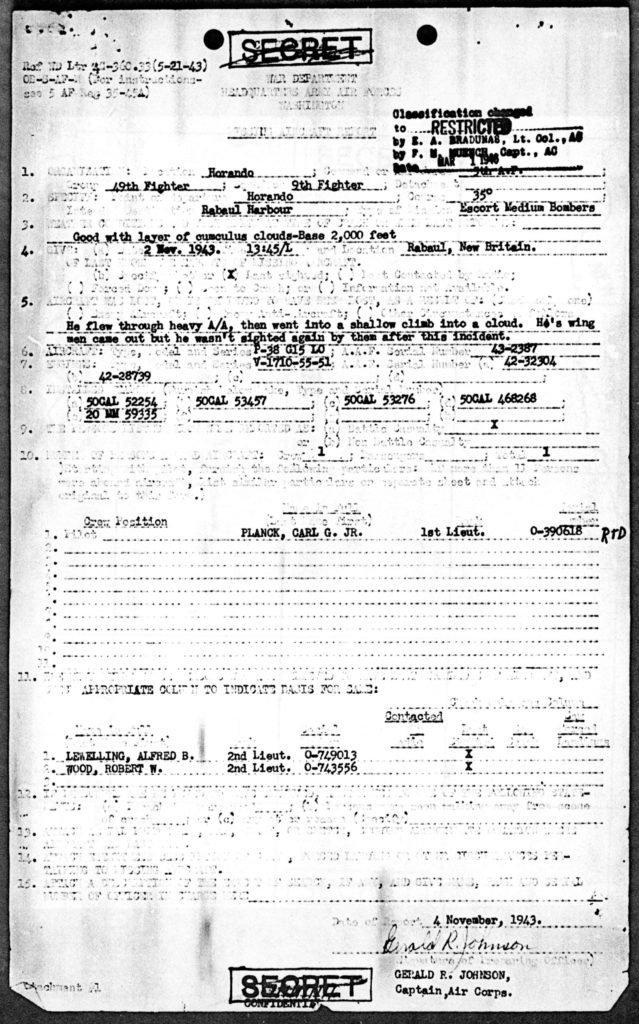

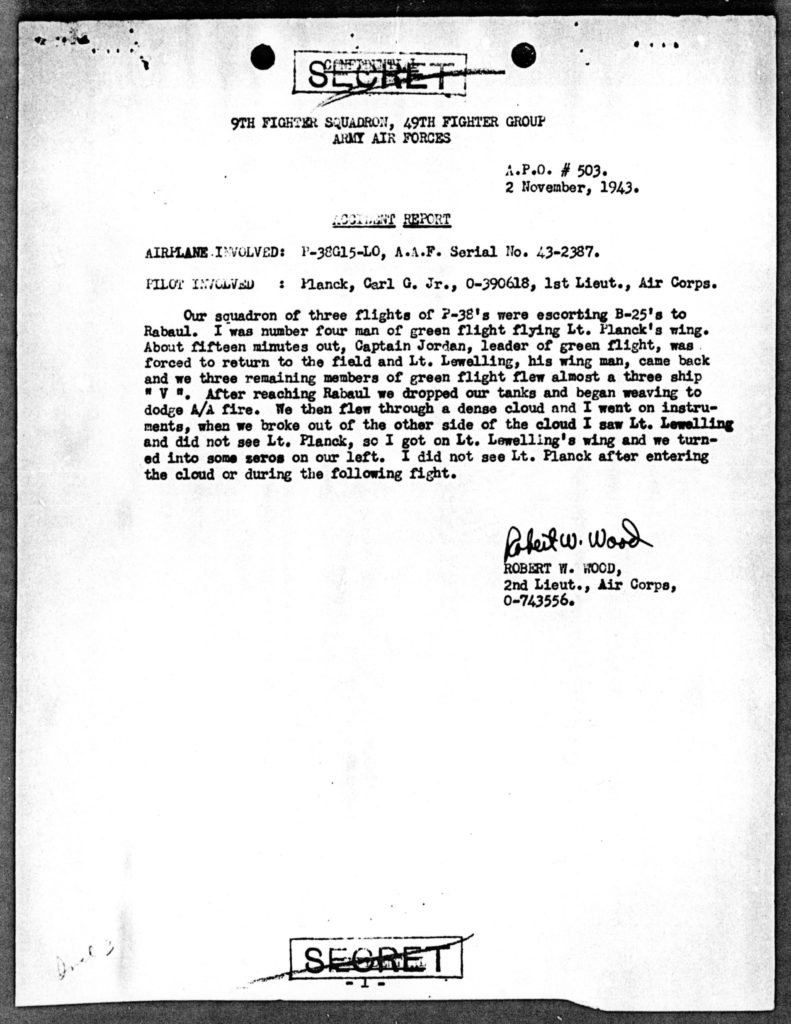

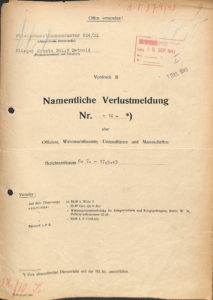

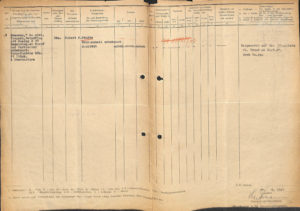

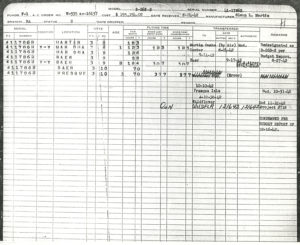

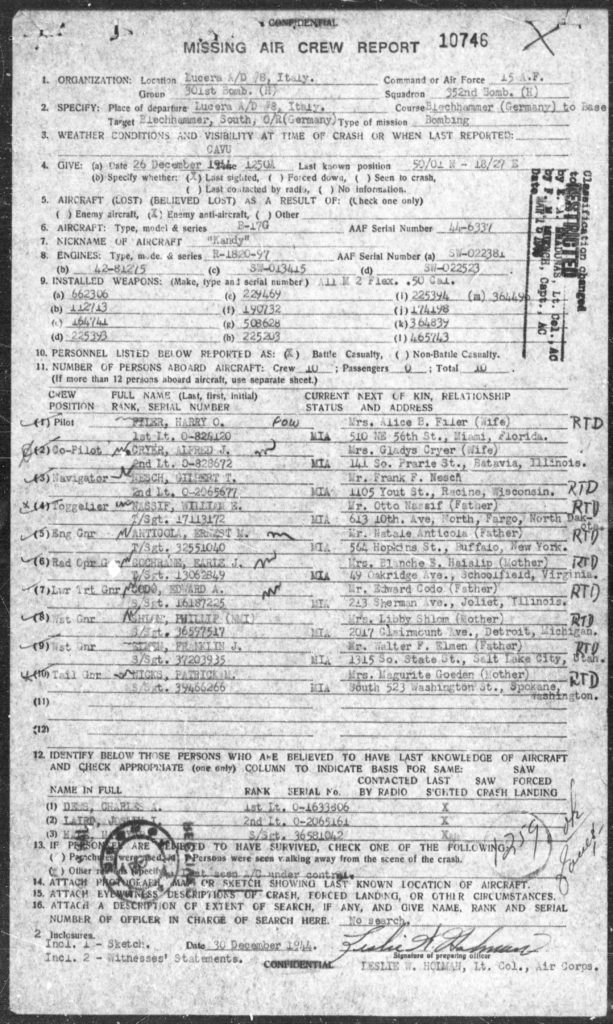

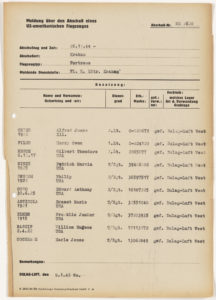

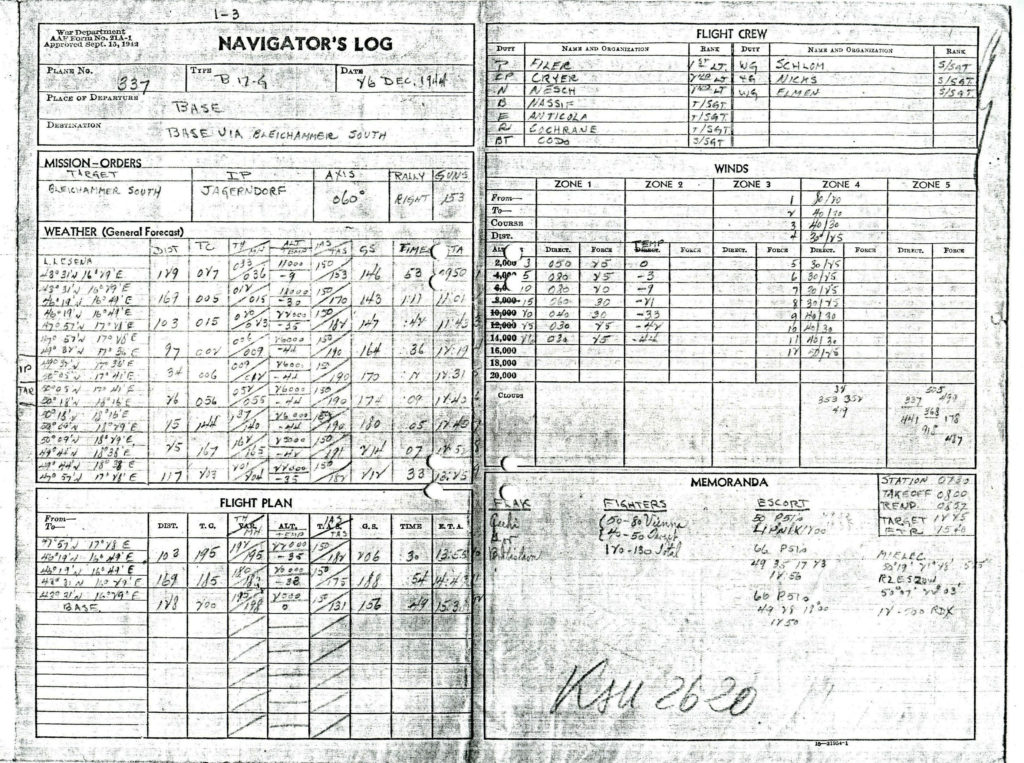

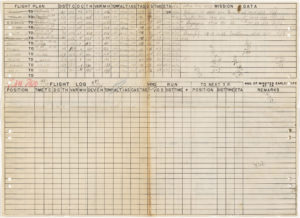

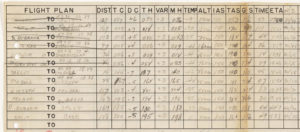

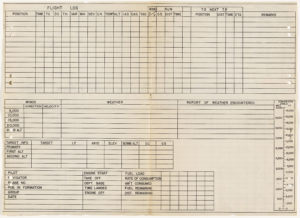

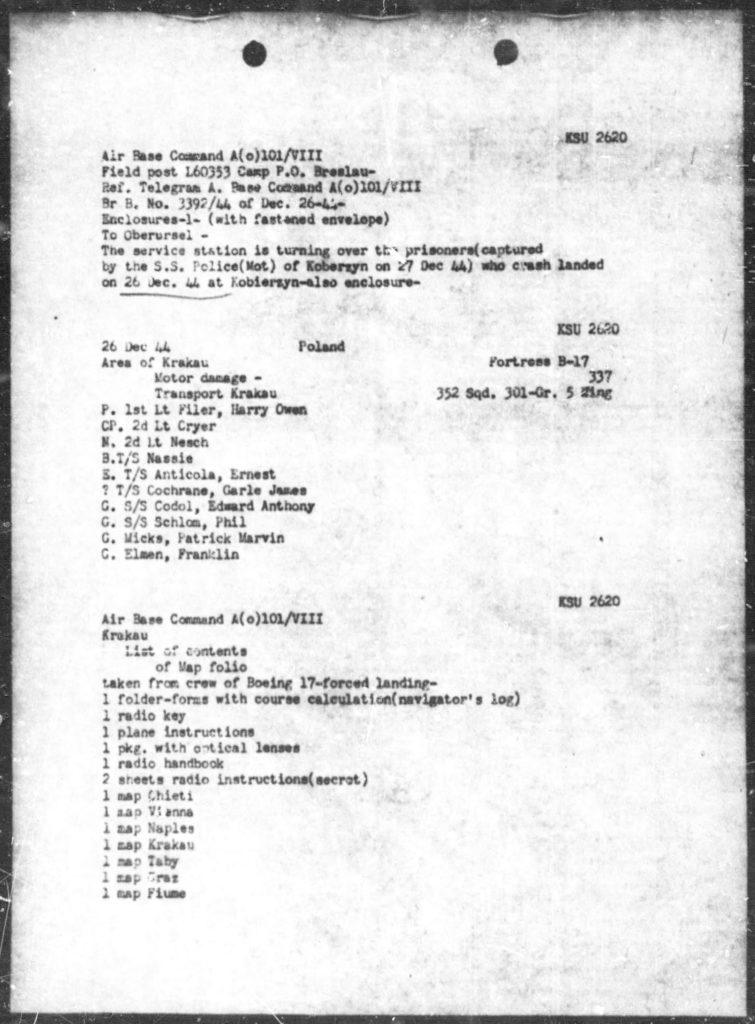

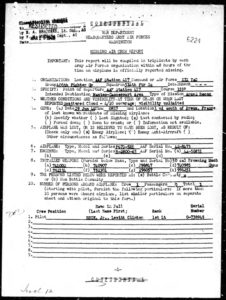

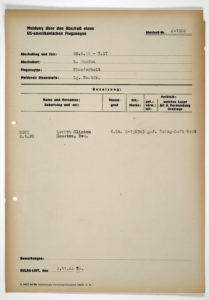

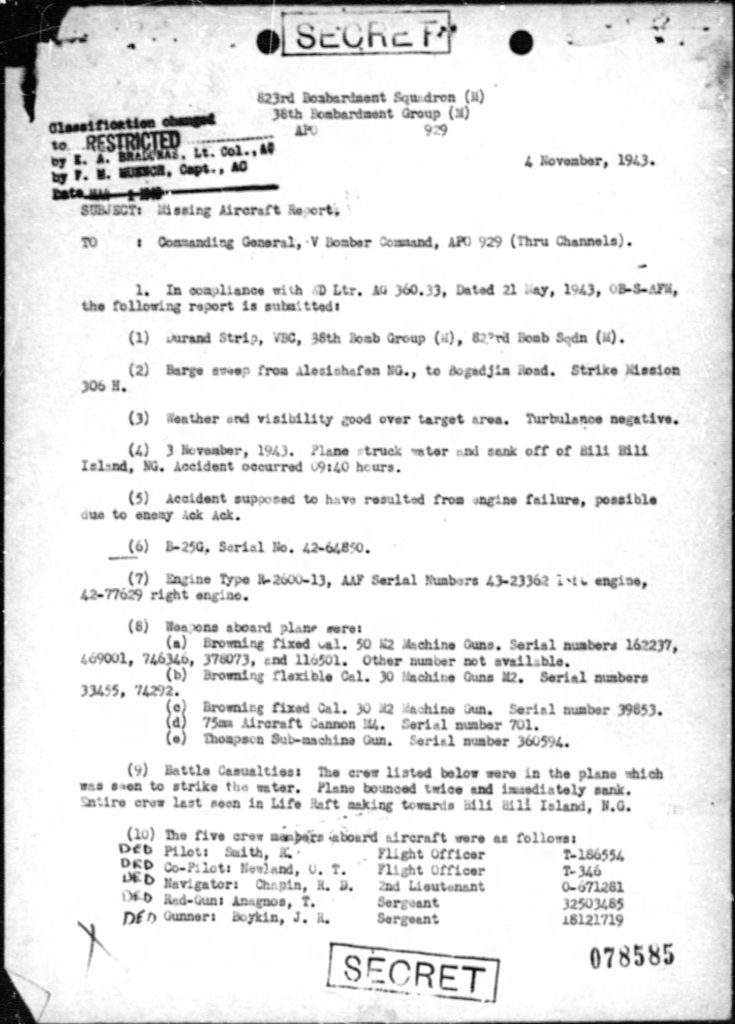

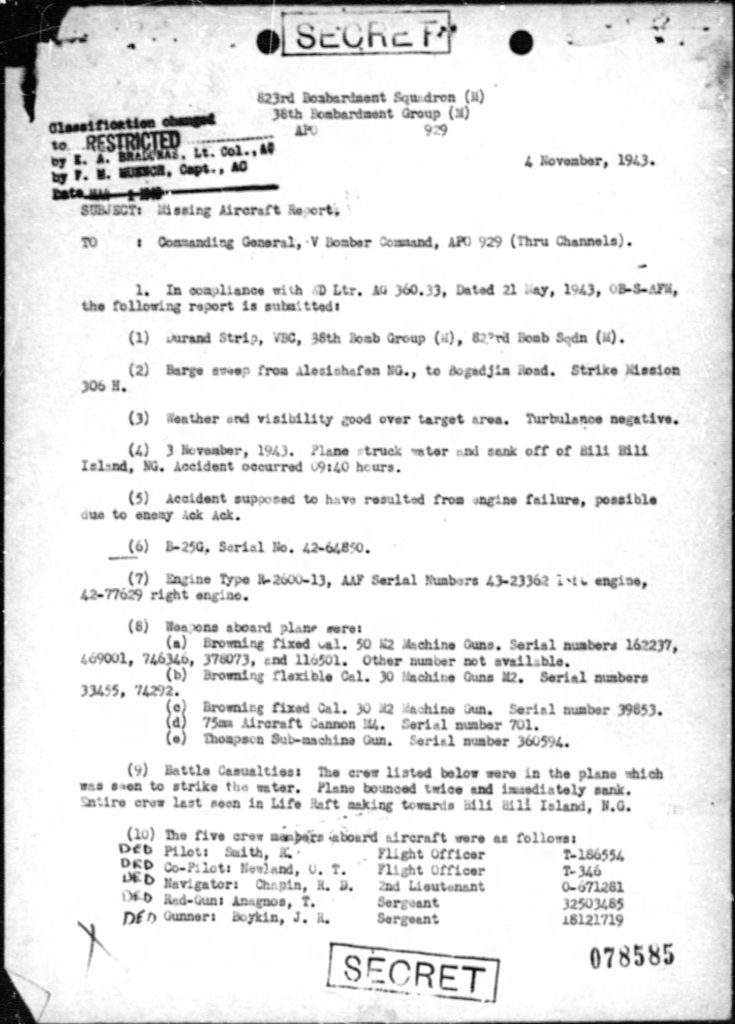

The “first” page of MACR 1087, covering the loss of B-25G 42-64850, a 75mm cannon-equipped ship – is shown below:

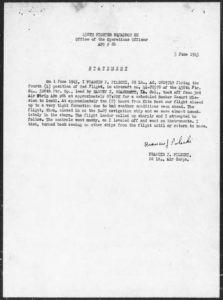

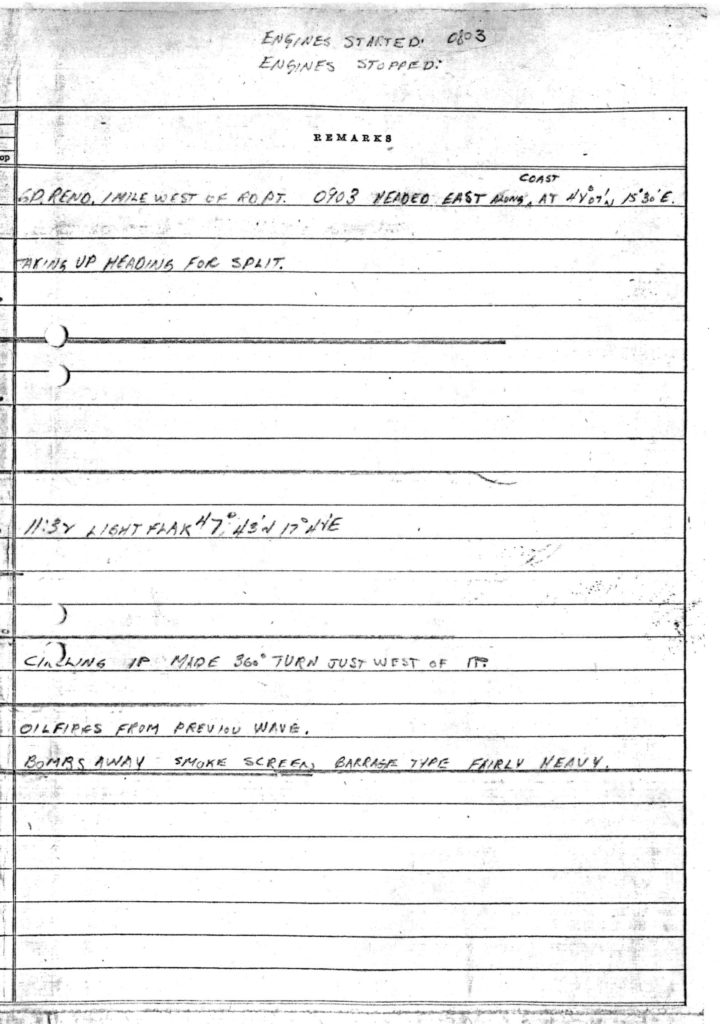

The following comments were recorded by the 823rd Bomb Squadron’s Statistical Officer, 2 Lt. Homer L. Cotham, and appear on the “second” page of the MACR:

The following comments were recorded by the 823rd Bomb Squadron’s Statistical Officer, 2 Lt. Homer L. Cotham, and appear on the “second” page of the MACR:

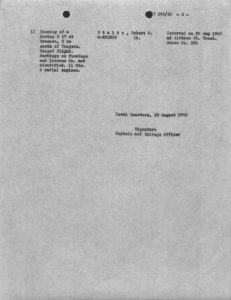

(12) Plane, while flying formation at low altitude over target, suddenly lost altitude striking water. The plane bounced twice, then sank immediately. Entire crew seen in Life Raft making for island in near vicinity of accident.

(13) Plane crashed in water four miles south of Madang, three-quarters of a mile off shore, in near vicinity of Bili Bili Island, N.G.

(15) Extent of search: Catalina flying boat attempted to reach vicinity of accident or crash the night of October [sic] third. This attempt was incomplete due to weather.

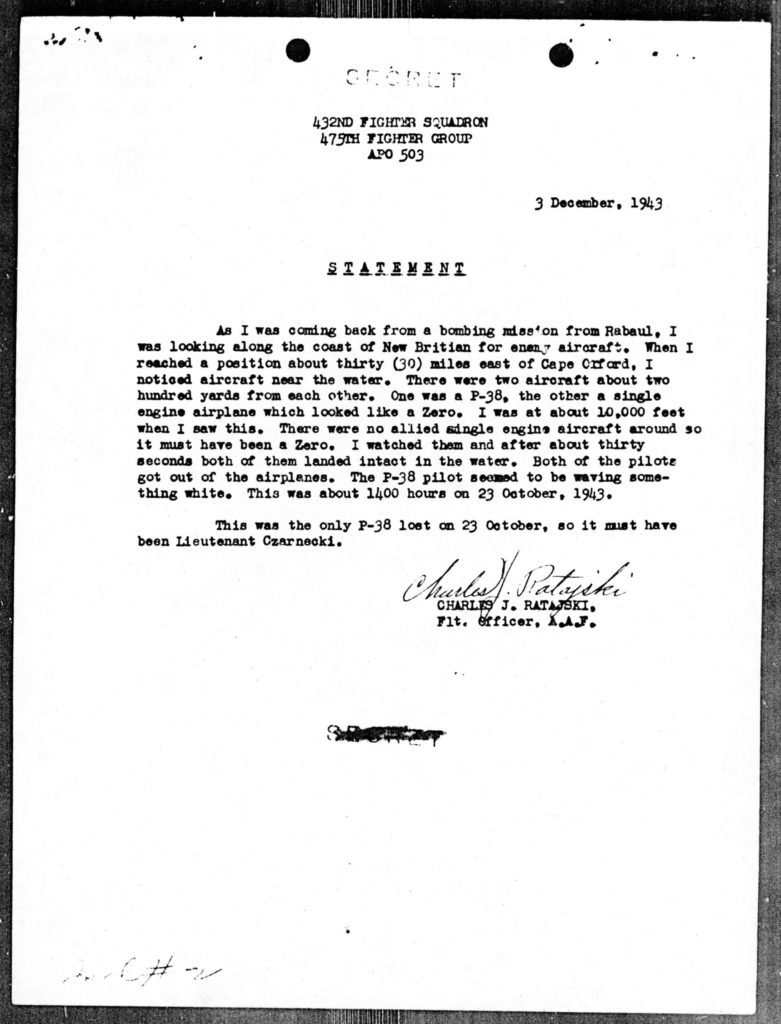

The plane’s loss was described by Squadron Operations Officer Capt. William Brandon, who stated:

While flying on Mission number 306 H, Alexishafen to Bogadjim Road Barge Sweep, I was leading flight number one. Flight Officer Smith was flying number three left wing position at the time that I took my flight in over the target. When next I looked to check the planes in my formation I saw Flight Officer Smith’s plane in the water.

Circling the plane as it sank I dropped a life-raft. This life-raft sank but the crew of the sunken plane were able to safely board the raft from their own plane.

When last sighted all members of the crew were observed aboard life-raft making towards the vicinity of Bili Bili Island, N.G., course undetermined.

______________________________

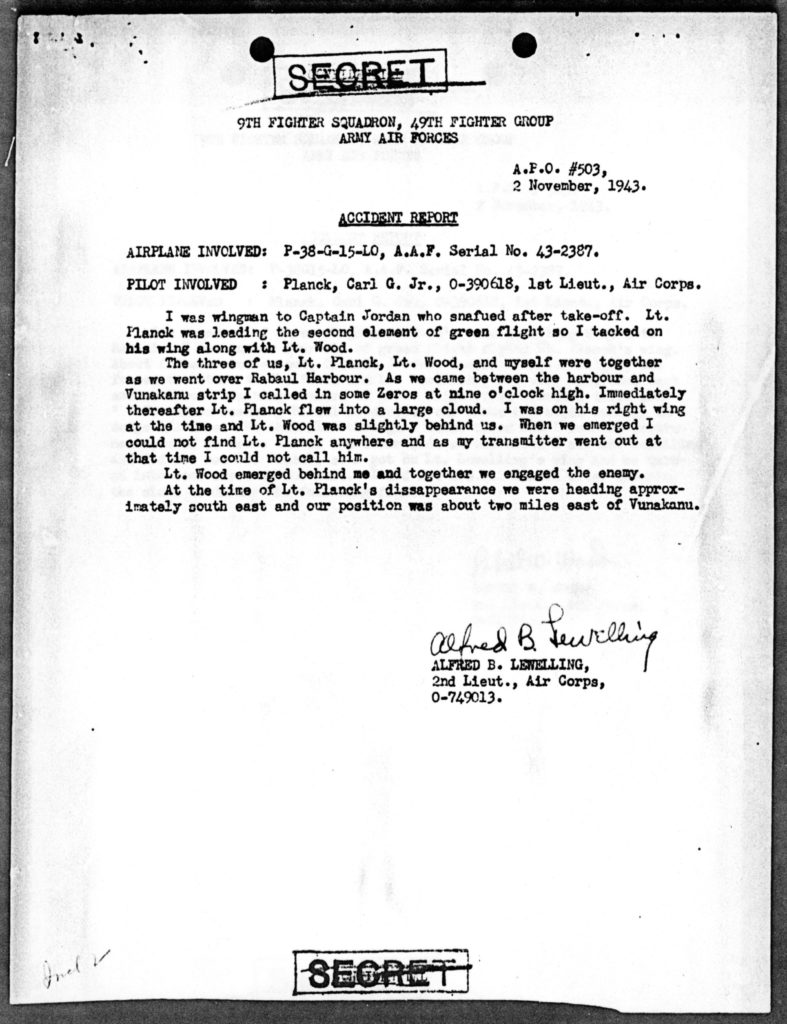

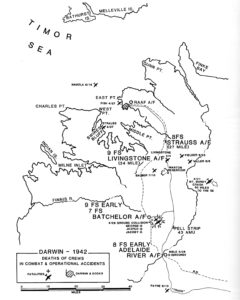

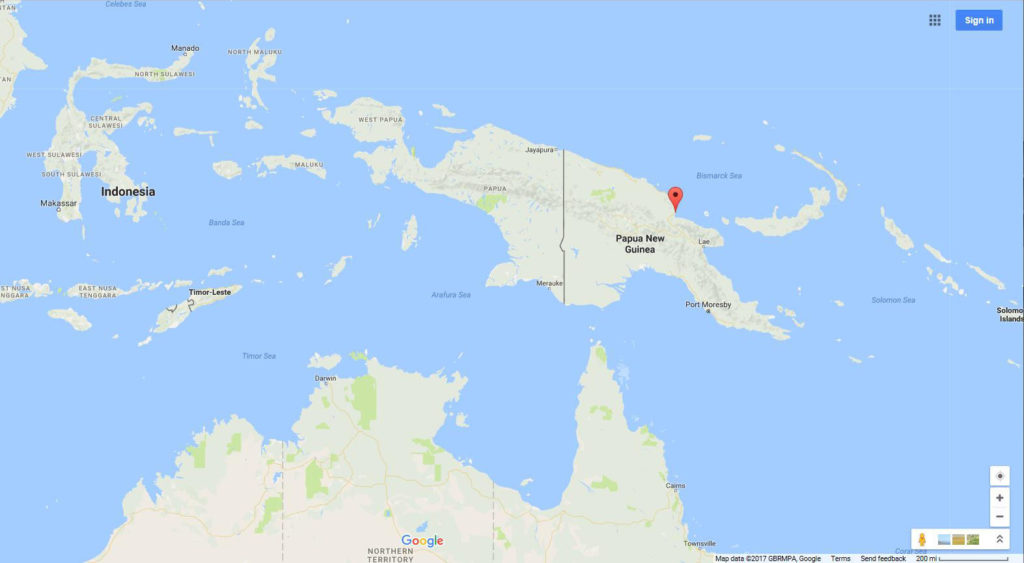

Unlike MACRs which specify the last-known latitude and longitude of a missing aircraft, the location of B-25G #850’s loss is simply given in words: “Off Bili Bili Island.”

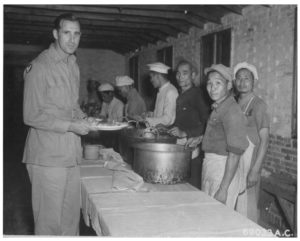

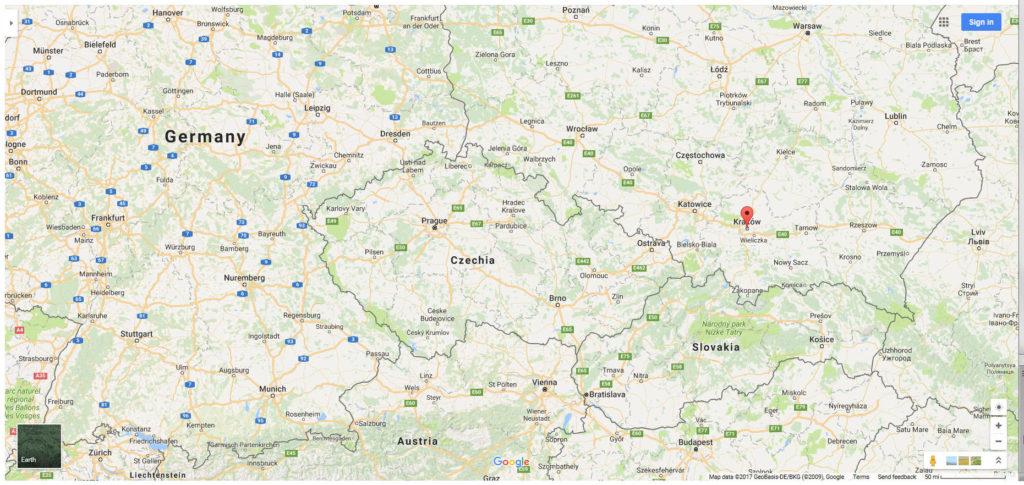

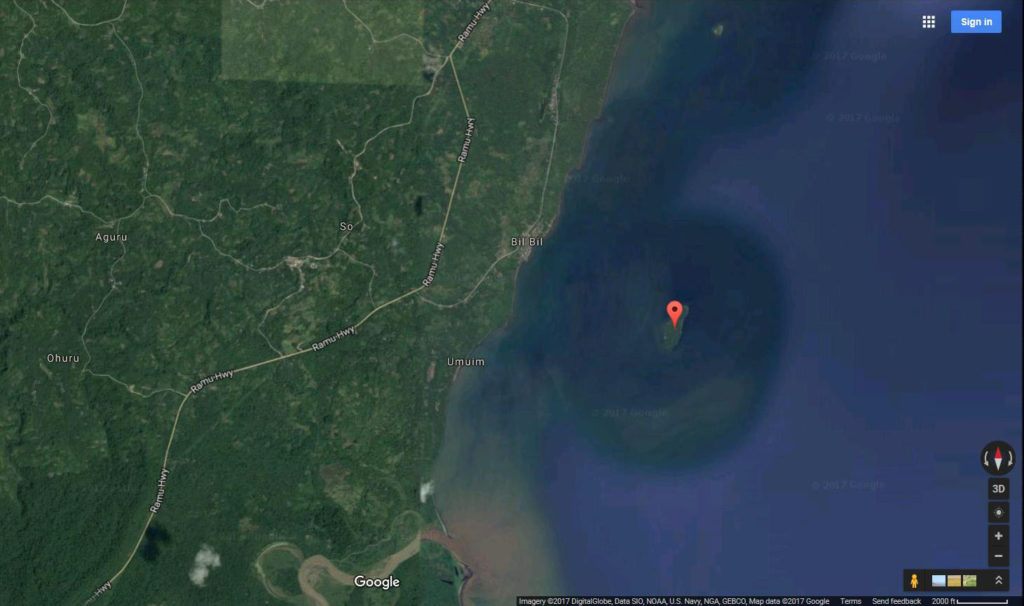

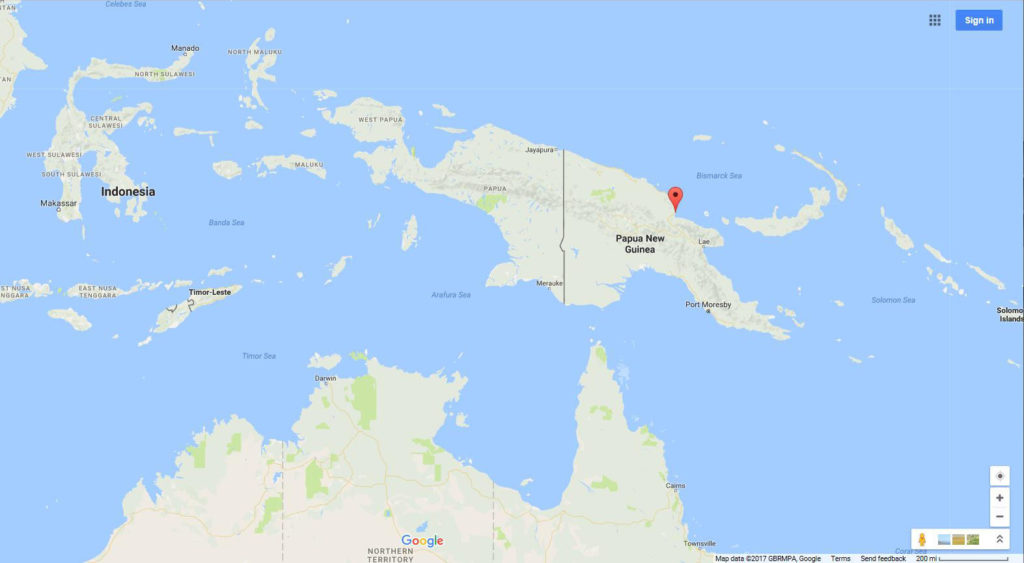

To give you a frame of reference of the location of Bili Bili Island, here are two Google Maps – each having Google Maps’ red location pointer centered upon Bili Bili Island – showing the location of that tiny geographic feature.

This first map shows New Guinea and northern Australia, with – moving west to east – the Arafura Sea, Gulf of Carpentaria, and Coral Sea between the two land masses. Bili Bili Island is located approximately 360 miles west-southwest of Rabaul, just off the eastern coast of New Guinea, and south of Madang.

______________________________

______________________________

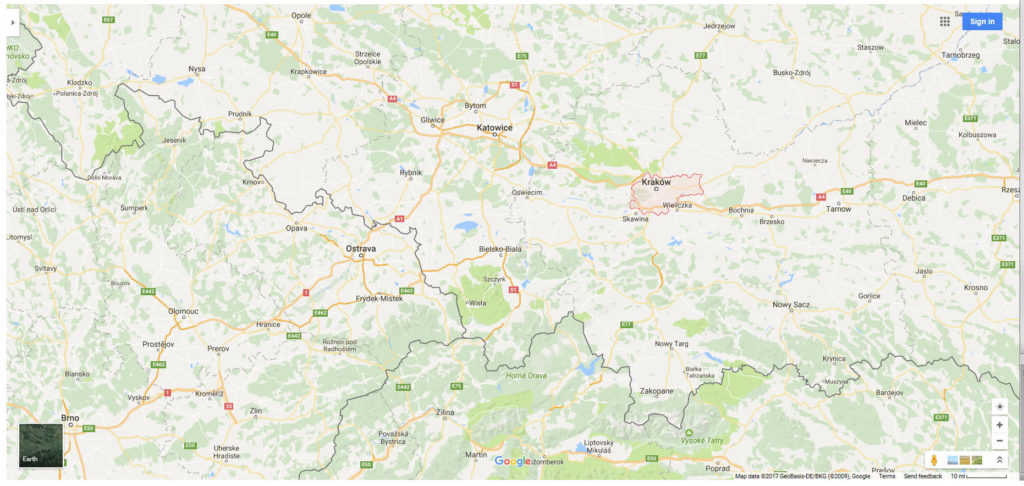

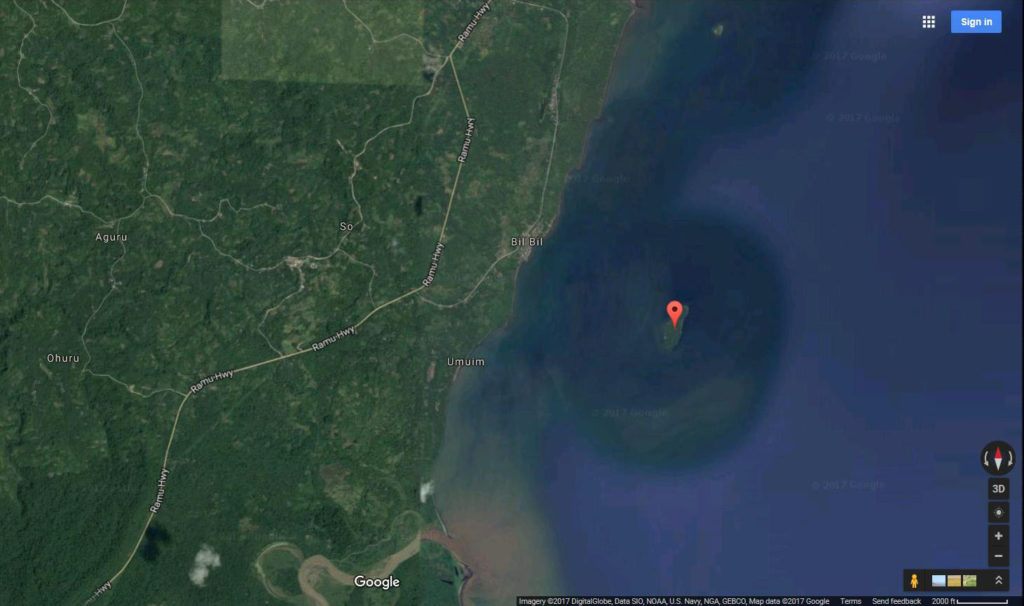

In this second map, Bili Bili Island is not visible, but locations mentioned in the MACR – Alexishafen and Madang – are. These towns lie along the western shore of Astrolabe Bay, which body of water remains unlabeled.

______________________________

______________________________

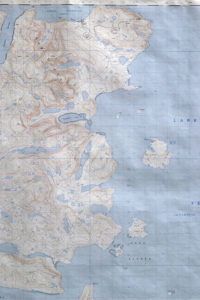

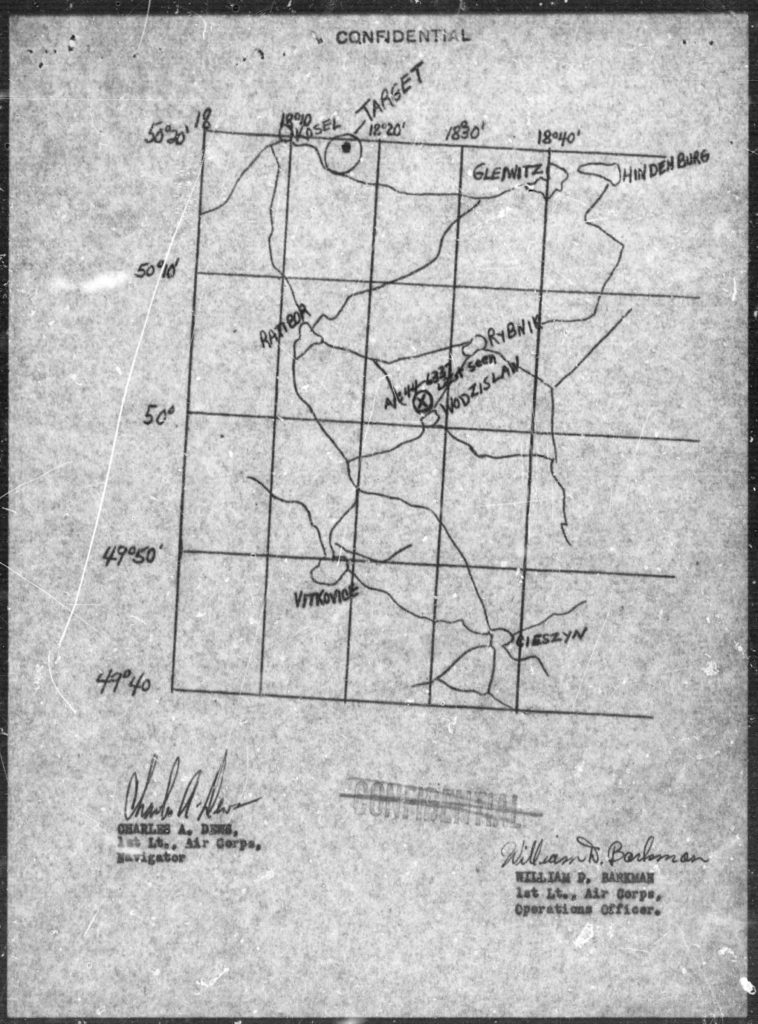

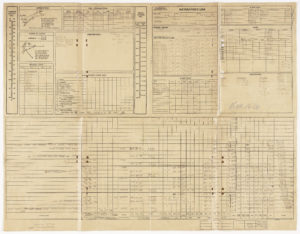

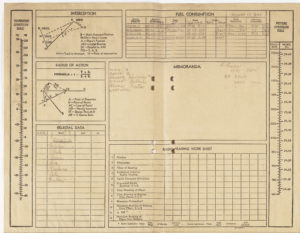

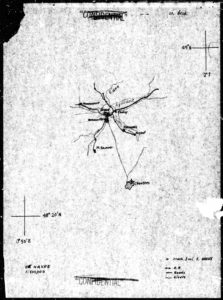

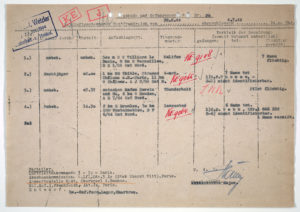

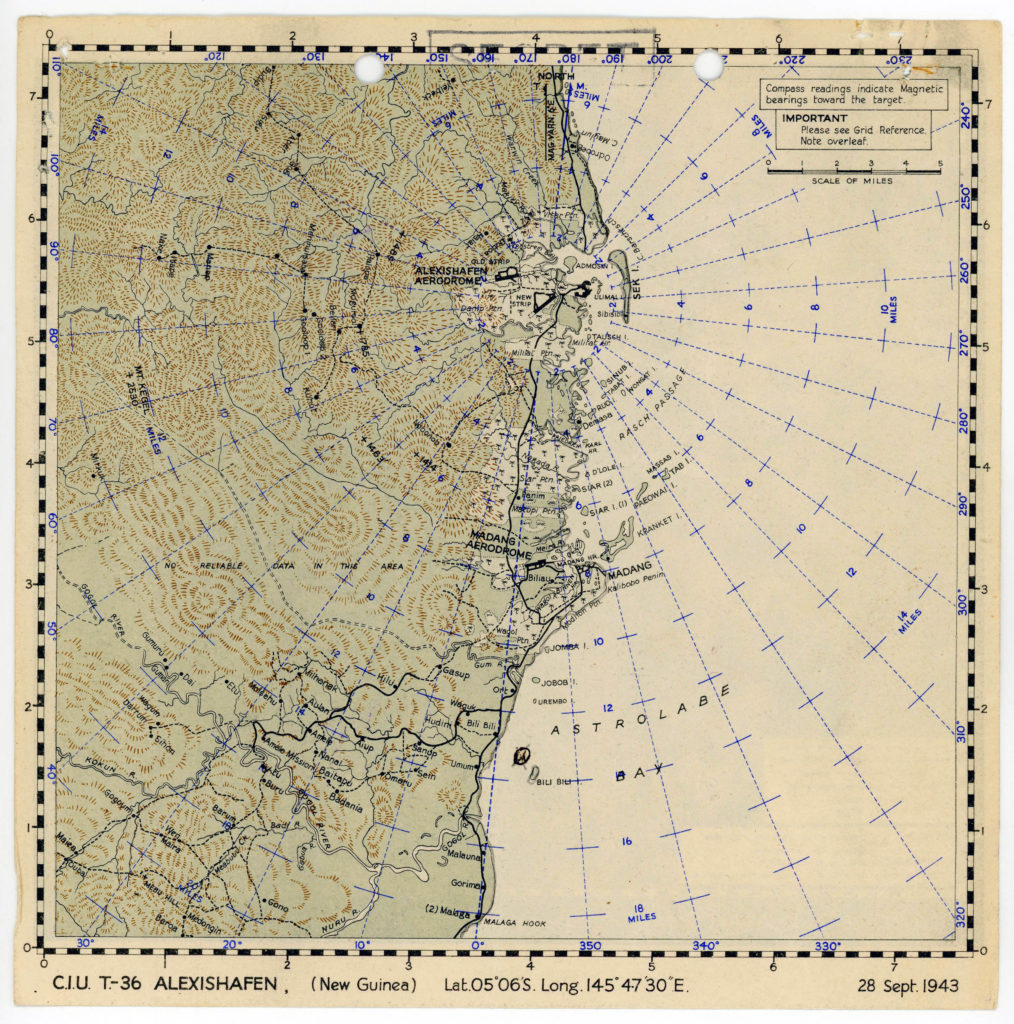

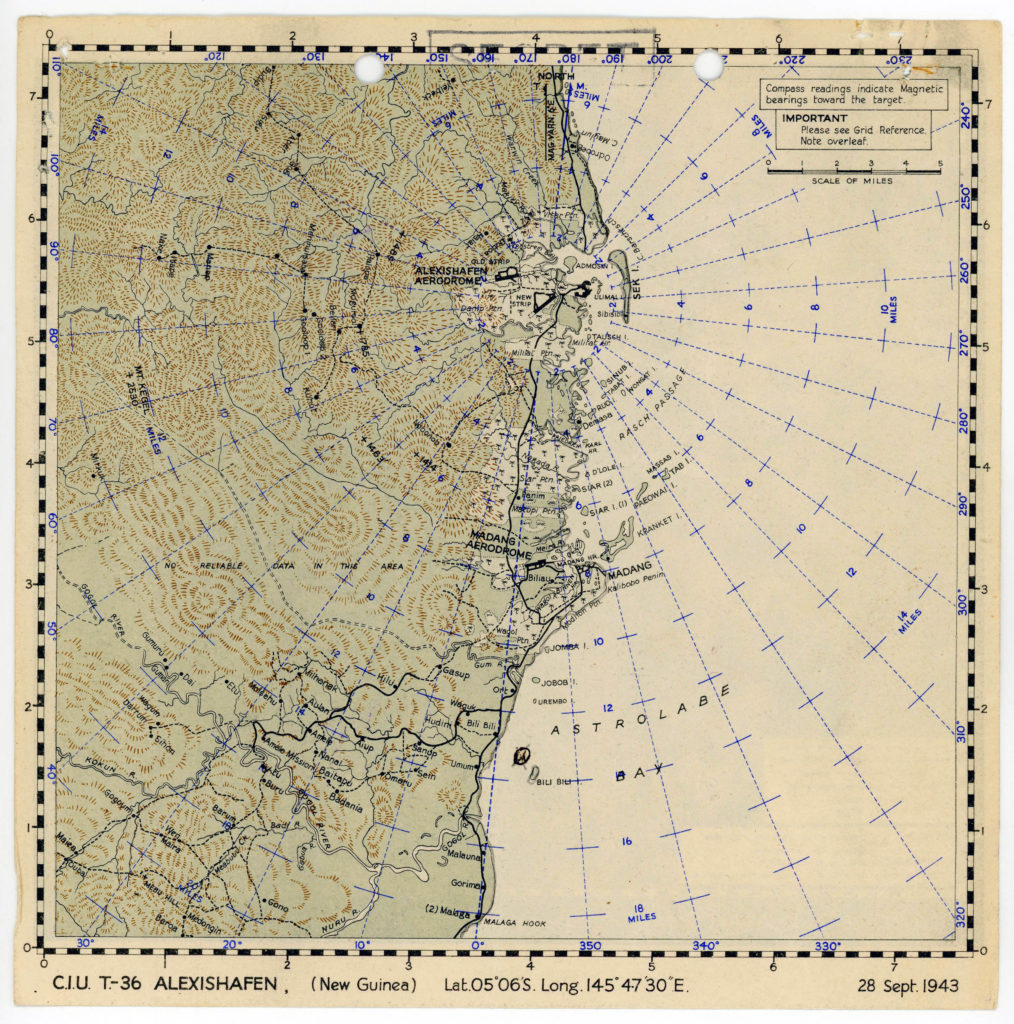

Moving from the pixels of 2017 to the paper of 1943, MACR 1087 includes C.I.U. (Central Interpretation Unit) Map No. 36 of the Alexishafen area. The location of the B-25’s loss, about half-way between Bili Bli Island and the New Guinea coast, is denoted by an “X” within a small circle.

(By way of comparison, here’s the map as it appears at Fold3.com.)

(By way of comparison, here’s the map as it appears at Fold3.com.)

______________________________

______________________________

At a slightly larger scale than the C.I.U. map is the Google map below. This closer view reveals that Bili Bili Island is approximately 3 miles south of the southern limits of Madang, and about 1.3 miles east of the New Guinea mainland. Oddly, Google Maps leaves the island un-named, with the designation “Bil-Bil” superimposed on the opposite shoreline. Is there a village by that name at this location?

______________________________

______________________________

Finally, at the same scale as the preceding map, we come to a Google Earth view of Bili Bili Island and Astrolabe Bay.

______________________________

______________________________

Pacific Wrecks clearly describes the loss of un-nicknamed B-25G 42-64850, surmising that the men were captured and died in captivity, while the Pacific Wrecks essay concerning the fate of allied POWs at Amron, New Guinea (Death at Amron – by Undersea Explorer / Documentary Film-Maker Walter Deas) suggests that the Smith crew may have murdered at that Japanese base, a “hilltop high-ground 16 kilometers north of Madang,” which served as a Japanese Army headquarters and Kempeitai facility.

Pacific Wrecks’ history of the Japanese Army base at Amron, which served as a lookout point and headquarters for the 18th Army and Kempeitai, lists the names of eleven Allied airmen (nine Americans and two Australians) who were confirmed to have been murdered at that location, and, five others who probably suffered the same fate, all between June, 1943 and April, 1944.

However, the members of the Smith crew are not listed among the sixteen.

______________________________

The Capture of the Smith Crew

The Smith crew were definitely captured. This information comes from three sources.

In reverse chronological order, these comprise the 2011 book Sun Setters of the Southwest Pacific Area – From Australia to Japan: An Illustrated History of the 38th Bombardment Group (m), 5th Air Force, World War II – 1941-1946, As Told and Photographed by the Men Who Were There (by Lawrence J. Hickey, Mark M. Janko, Stuart W. Goldberg, and Osamu Tagaya); 1944 newspaper articles in (unidentified) Buffalo area newspapers, and most strikingly, transcripts of English-language Japanese propaganda broadcasts to the western United States covering the mens’ capture

In 2011

As described in Sunsetters: “Capt. Bill Brandon led the 823rd Squadron, and when his flight of three planes reached Bili Bili, roughly halfway between Alexishafen and Bogadjim, he and his wingmen dropped their bombs between the area’s plantation and Bili Bili Island, just off the coast. As his bomb bay doors were closing, Capt. Brandon looked out his window and was shocked to see that Flight Officer Richard Smith’s plane was in the water.

Brandon circled back and dropped a life raft to the downed crew. Smith’s plane sunk immediately after hitting the water, but he and his crew escaped and climbed into the raft. The men were last seen rowing toward Bili Bili Island, where they were captured and interrogated by the Kempei Tai, the Japanese Military Secret Police. Major Nakamoto, the 18th Army Staff Intelligence Officer, led the interrogation, which lasted roughly a week. Afterward they were taken a mile southwest to a POW compound, then transported to Wewak. They were never heard from again.” (Unfortunately, there no bibliographic reference for the source of this information.)

Pacific Wrecks history of the Wewak POW Camp (Kreer POW Camp) lists the names of three airmen (members of Captain William L. “Kizzy” Kizzire’s crew, about whom see more below) who were confirmed as having been POWs there. Neither they, nor any other Allied POWs presumed to have been held captive at that location – the Smith crew among them? – survived the war.

Late 1943 and early 1944

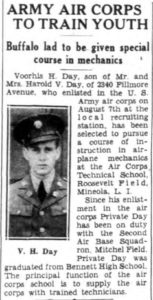

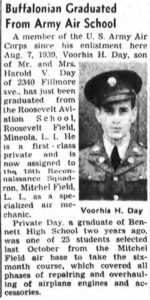

News items concerning F/O Smith from The Buffalo Evening News.

The first news item simply mentions Smith’s “Missing in Action” status.

Flight Officer Richard Smith

Overseas since last March, Flt. O. Smith has been stationed in New Guinea and had been piloting a bomber. His last letter to his mother was written Nov. 3, the day on which he was reported missing while on a mission over New Britain. Graduated from District School 3, West Seneca, and West Seneca High School, he was a carrier for The Buffalo Evening News before entering the employ of the Bethlehem Steel Company. He enlisted in the Air Forces June 28, 1941.

News about F/O Smith’s capture was published in February or March of 1944, in the context of news about the death of his cousin and fellow Buffalo resident, Army Private Floyd C. Smith.

WAR-SERVICE FLAG HONORING 4 SMITHS NOW HAS GOLD STAR

Patrolman Wayne Smith, a grizzled veteran of 20 years’ service as a West Seneca policeman, went about the sad task of replacing one of the four blue stars in the family’s service flag with a gold star today. He has just been notified by the War Department that his son, Pvt. Floyd C. Smith, 19, who had been previously reported missing in action in Italy, now is known definitely to have been killed.

What makes the news even more tragic for the smith family is that over on the other side of the world Flight Officer Richard Smith, 23, a nephew of Patrolman Smith, is a prisoner of the Japs. Richard is the son of Albert Smith, an electrician, of 17 Klass Ave., West Seneca, and was taken prisoner last Nov. 3, when a twin-engine bomber he was flying was forced down on a flight from New Guinea to New Britain.

Two other members of the Smith family are in the nation’s service. One is Pvt. Wayne Smith Jr., 21, a brother of Floyd, who has been unheard of in recent weeks and is believed to be overseas, and the other is Seaman First Class Milton D. Smith, 38, an uncle of Floyd and Richard, who is now at sea. Milton’s home address is 80 Hayden St., Buffalo.

“I guess the war is proving kind of hard on the Smiths,” commented Patrolman Smith in his home at 25 Harlem Rd., West Seneca. “But I guess the same thing is happening to the Smiths all over the country. I wish I were a little younger I’d go in and take Floyd’s place. The last word we received from Floyd was about seven weeks ago when he wrote that ‘everything is swell’. Shortly after that he was reported missing. But we didn’t give up hope until the second telegram came.”

Floyd was inducted in the Army in April 1943 after he had been working at the Curtiss-Wright Corporation airport plant for about five months. He was a native of West Seneca and was in his third year at West Seneca High School when he left school for war work. Assigned to an infantry unit, he had been in North Africa before going to Italy.

News of his death has been kept from his grandmother, Mrs. Fannie Smith, who is ill and also lives at 25 Harlem Rd., West Seneca. (1)

A particular sentence in the article stands out: “Richard … was taken prisoner last Nov. 3, when a twin-engine bomber he was flying was forced down on a flight from New Guinea to New Britain.”

How was this known by early 1944?

Probably through English-language radio broadcasts transmitted from Tokyo, and beamed to the Western United States and Latin America, from…

November of 1943 through April of 1944.

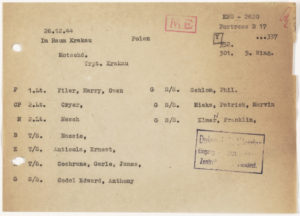

Entitled “Message From the Front”, these broadcasts pertained to American aviators – members of the Marine Corps and Army Air Force – who had been captured in the Southwest Pacific between early 1943 and early 1944.

Transcripts of these broadcasts are among records in the National Archives and Records Administration’s “Records of the Foreign Broadcast Intelligence Service.”

The “Message From the Front” broadcasts were transmitted at 0330 hours, albeit transcripts of the programs don’t specify if “3:30 hours” means Greenwich Mean Time, the Western time zone of the United States, or, Tokyo Time. The transcripts are headed by a surname, presumably that of the person who monitored and transcribed the program as it was received and monitored, in “real time”. These people were Berman, Bernstein, Hanson, Keller, Litwin, Roth, Sachter, Searl, and Teel.

Though varying greatly in content and length, the broadcasts follow a generally similar “script,” albeit with substantial variation. They generally commence with an introduction covering political or social effects of the war on American Society, as a whole. Sometimes, emphasis is placed on the contrast between the hardships endured by American soldiers and civilians, in contrast with the attitude – as it were – of American military and political leaders.

Then, the broadcasts focus upon the POWs themselves.

In all cases, the bulk of the broadcast is devoted to a presentation of detailed – quite detailed; very detailed – biographical information about the Prisoner of War, and may cover such topics as the circumstance under which he was shot down and captured, the type of aircraft he was flying, and his biography, the latter including his education and civilian vocation. In virtually every case the broadcast concludes with a recitation of highly personal, information about his next of kin, comprising names and addresses of family members – whether wives, parents, or siblings – the material, financial, or emotional challenges they’re contending with, and, other facets of their lives.

In some cases – disquieting to read; still disquieting to contemplate, even decades later – special focus is accorded to the physical, psychological, and emotional reaction of the POW to captivity, sometimes including quotations of statements allegedly made by the POW to his captors.

It’s conjecture on my part, but I suppose that the information in the “Message From the Front” broadcasts was extracted from transcripts of interrogation sessions endured by the POWs, then provided to officials in the Japanese media responsible for disseminating propaganda. The original text was edited to varying degrees for maximum dramatic effect.

In that sense, a consistent and unsurprising facet of the broadcasts is the complete absence of information about American military technology or tactics. Unsurprising, in that the purpose of the broadcasts was probably psychological warfare: To influence public opinion and therefore contribute to a sense of demoralization. If this was so, this rested on an extremely naive understanding of the nature of American society. (At least, as it existed eight decades ago. But, that’s another subject.)

In terms of the Smith crew, “Message From the Front” broadcasts pertain to Sgt. Boykin (February 9, 1944), Sgt. Anagos (February 16, 1944), Lt. Chapin (March 8, 1944), and F/O Smith (on March 29, 1944). There is no record of a broadcast concerning F/O Newland.

For the purpose of this post, two transcripts will suffice.

Here is the broadcast covering Sergeant Anagos, transmitted on February 16, 1944, as transcribed by “Roth” and “Teel”:

A MESSAGE FROM THE FRONT

Your subject for today is the Boeing bomber that flew on without a pilot. Hello listeners, this time Radio Tokyo presents an eye-witness report from a member of the Japanese army press participating at a certain front in the New Guinea sector. Yes, it is a very strange story. It is worth coming under the category of believe it or not. It is an unusual story for the outsiders but it is [stunning] news for no other person than Mrs. Phyllis Anagnos, whose address is eight-four-one-seven North Military Avenue, Detroit, Michigan. Should it happen that Mrs. Anagnos is listening to this broadcast, radio Tokyo advises here to keep up [word]. It is so far from being good news, but a very depressing [two words] can be seen. Well, she may feel easy that her husband Sergeant Theodore Anagnos is no by means dead. Instead of ending his life, he has been taken prisoner by the Japanese forces, [and being a prisoner] of war, he cannot return to his beloved wife so long as America does not make unconditional surrender to Japan. If Mrs. Anagnos wishes to see her husband, she had better write a letter to Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt asking for help. No doubt the sympathetic Mrs. Roosevelt might take it that she might be under the circumstances with the wife of [few words]. Mrs. Roosevelt [three words] cell every day at the White House wailing bitterly before President Roosevelt and insisting upon the release of Theodore Anagnos. Well, wait a moment, Mrs. Theodore Anagnos is yet happy because her husband is enjoying good health at a prisoner’s camp of the Japanese Army. One day he told a member of the Japanese Army [press], that he saw at a certain American movie show [three words] featuring Clark Gable. He said Gable was [wonderful]. He went on to say I have a wife but to tell you the truth, I have [few words] how marvelous it would be if I could see [several words]. It is as if I am playing the very same role as Gable was in this film. Sergeant Anagnos [few words]. Mrs. Anagnos can depend upon it that her husband is quite [jovial]. Radio Tokyo is not responsible for his relationship with [two words]. That is a matter for Mrs. Anagnos to conduct a cross examination of her husband in person, in the event he should come back to America.

[Remainder of commentary unintelligible.]

Here’s the broadcast covering Flight Officer Smith, transmitted on March 29, 1944, as transcribed by “Hanson”:

MESSAGE FROM THE FRONT

Once again we bring you information of the officers and men [seven words inaudible].

Radio Tokyo proposes to give you details that are not available from any other source. Many of the folks back home are not told that a large number of their boys are being held prisoners of war in Japanese hands. These boys are spending their daily life in an entirely different frame of mind – I say different in the sense that their outlook of life in general at the time when they sallied forth from the United States is no longer apparent. Having become accustomed to their new environment, they have regained their presence of mind. Yes, they have come down to earth. They are now able to see through the realities of things in general. Like an ancient philosopher, they have had an ample opportunity to reflect on the past and quietly analyze the present.

Here is the story of one of the men as brought to us by a Japanese Army correspondent. His name is Richard Smith. To be more concise, Richard Smith is a Second Lieutenant belonging to the Twentieth Bomber Squadron, and the Fifth Bomber Group of the United States Air Corps. Smith is twenty-four years old and hails from Buffalo, New York. The address is Seventeen Klaas Avenue, Buffalo, New York. Second Lieutenant Richard Smith was a pilot at the time of his capture.

Anyone listening on this broadcast will be doing a great favor for Richard and his folks if he, or she, would notify Mr. Albert Smith, the father of Second Lieutenant Richard Smith, at Seventeen Klaas Avenue, Buffalo, New York, that his son is in good hands under the care of the Japanese army authorities. The War Department at Washington may have listed him as missing, as they have done to hundreds of others. But as far as Second Lieutenant Richard Smith is concerned, he is very much accounted for, and in good shape, as a prisoner of war of Japan.

One of the things that Second Lieutenant Richard Smith inquired of our Japanese army correspondent is whether or not there were other officers in active service who come from Annapolis. By the way, I mean to add that Second Lieutenant Richard Smith is an Annapolis man. He would like to know why it is that there were no other Annapolis men on the front line. The officers that had come across were all reserve officers. Second Lieutenant Smith is anxious to know whether it is the policy of the War Department at Washington to spare the services of all full-fledged academy men. One can fully appreciate the complaint on the part of Smith of being placed on the front line while his colleagues are being given posts in [such safe] positions well to the rear.

Another point brought out by Second Lieutenant Richard Smith was the fact that there is too much favoritism given to the pilots over the ground troops. One of his friends at Port Moresby was a member of the regular [crew]. According to Smith, the pilots are given two weeks furlough after serving two and a half months on the front lines; whereas, the ground forces are allowed but one week after four solid months of drudgery.

Here is a tip from Second Lieutenant Richard Smith to the young men back in the States. “If you are ever counting on serving the United States Air Corps, stick to the flying end and steer clear of any jobs oiling and repairing planes, which one has no chance of flying [himself].” Of course, as Smith would put it you are taking chances against one of the toughest enemies, the Japanese Zero fighter. Whether you care to agree with Second Lieutenant Richard Smith or not, the fact remains that there is a wealth of difference between being a pilot and being just one of the boys in the ground force.

Another factor pointed out to our Japanese Army Correspondent by Second Lieutenant Smith that once you are sent out on the [word] front, there is no chance of knowing just what the score is. It is common knowledge that the United States Army Air Corps is a fanatic stickler for the “hush hush” policy of keeping all things under cover. I mean among the officers and men themselves. According to Second Lieutenant Smith, he knows the name and rank of his squadron commander but he has yet to hear the name of his group commander. Worse than that, he has never seen the face of his group commander. None of his comrades seem to know for that matter. Where is there any army that knows not the identity or the name of his superior officer? Second Lieutenant Richard Smith is in dead earnest, as anyone can tell that he wasn’t telling a lie. He really doesn’t know. Here is the great American mystery of an officer who does not know, or rather, he is not told just who are his comrades even in [his adjoining fortress].

Asked why he could not become more intimate with the other officers, Second Lieutenant Richard Smith said that he had been warned by his superiors to avoid mixing with the other officers. Hence, he had no knowledge as to the number or the designation or what had become of many of the officers once they [leave] [word or two]. The question naturally arises, “Why are the American air officers forbidden to associate with each other?” The answer is simple. It is the policy of secrecy. The authorities are on pins and needles in trying to keep all information as to the personal losses from reaching the ears of the men. Any divulgence of actual losses incurred by the United States Army Air Force [several words] would no doubt unbalance the morale of the rank and file. So there you are. It’s a mighty wise policy for a [word] which has lost quite a number of his valuable men to keep that information under a tight lip. What chances are there for the people back home to know just what has become of their boys? At least, the folks of Second Lieutenant Richard Smith can congratulate themselves on the fact that their boy is [quite safe and sound].

Though these two “Message From the Front” broadcasts were transmitted on February 16 and March 29, that fact does not imply that the POWs were still alive at that time. Some “Message From the Front” broadcasts were transmitted on dates after the POWs to which they pertained were no longer alive.

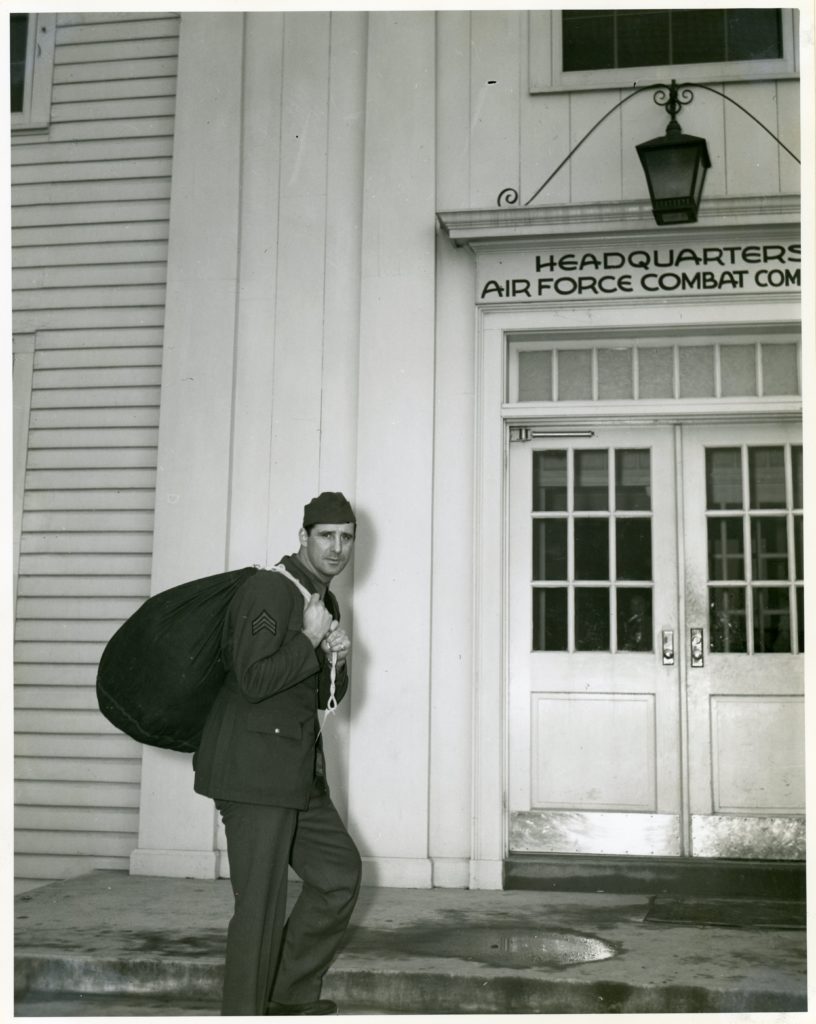

For example, 1 Lt. Joseph W. Hill (husband of Roberta Hill, of 602 Palmetto Ave., De Land, Florida) of the 70th Fighter Squadron, 18th Fighter Group, lost on August 26, 1943, while flying P-40F 41-19834.

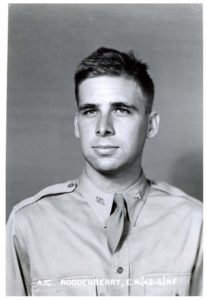

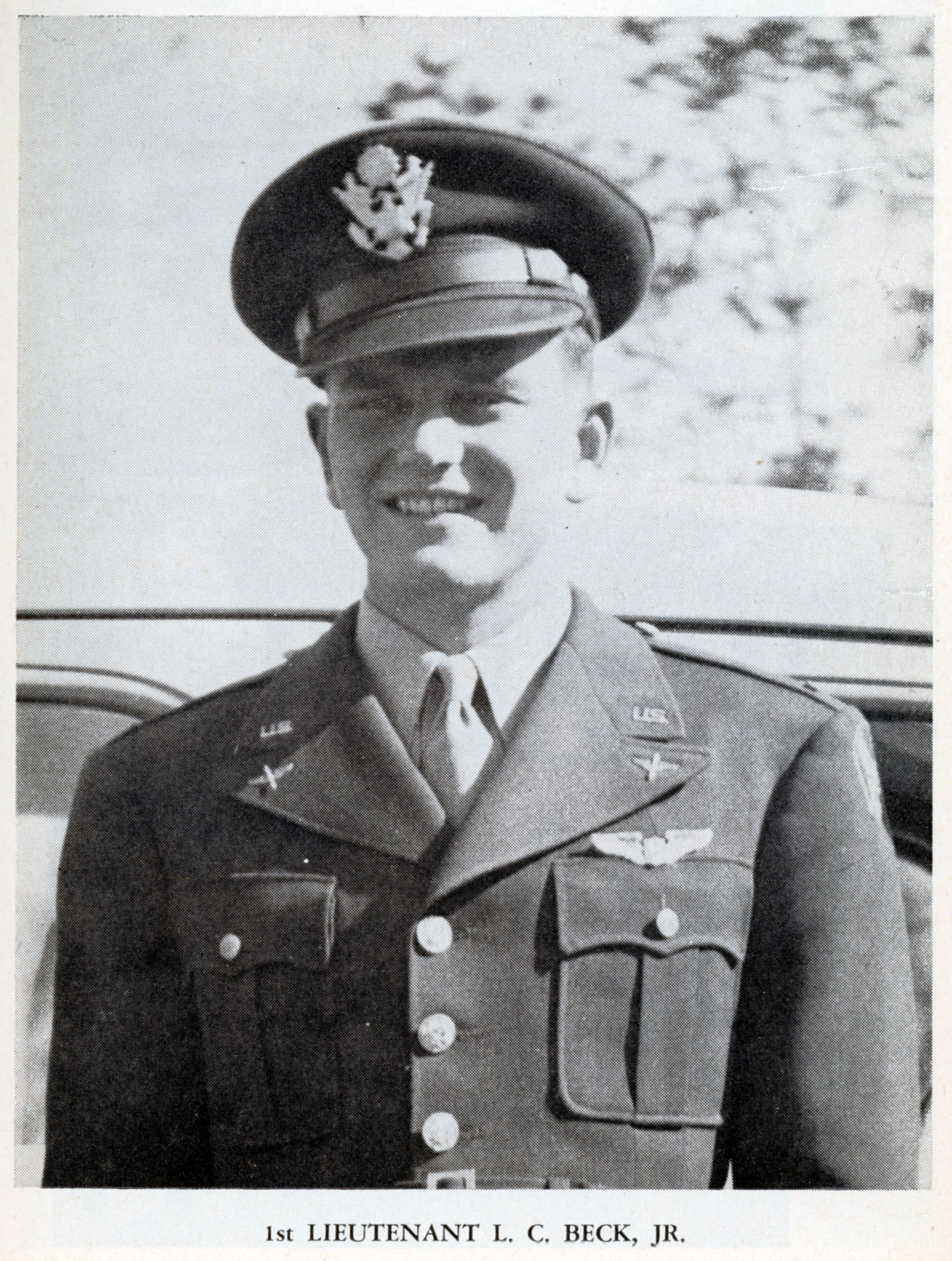

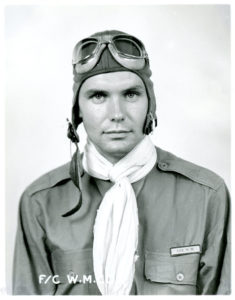

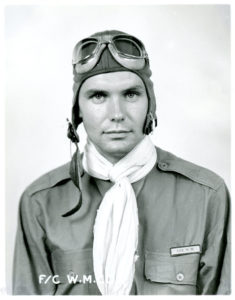

Captured and held captive at Rabaul, he was the subject of a broadcast on April 29, 1944. Nearly two months before, on March 4 or 5, 1944, he was one of the 32 American and Australian POWs (19 USAAF, 5 USMC, and 8 RAAF) who were murdered during the “Tunnel Hill Incident”. Lt. Hill’s flight school portrait, one of the thousands of similar images in the National Archives’ collection “Photographic Prints of Air Cadets and Officers, Air Crew, and Notables in the History of Aviation – NARA RG 18-PU”, appears below:

As for the Sunsetters, only one member of the Group survived captivity. He was Major Willison Madison Cox, of Knoxville, Tennessee. (3)

As for the Sunsetters, only one member of the Group survived captivity. He was Major Willison Madison Cox, of Knoxville, Tennessee. (3)

______________________________

What then, of the Smith crew?

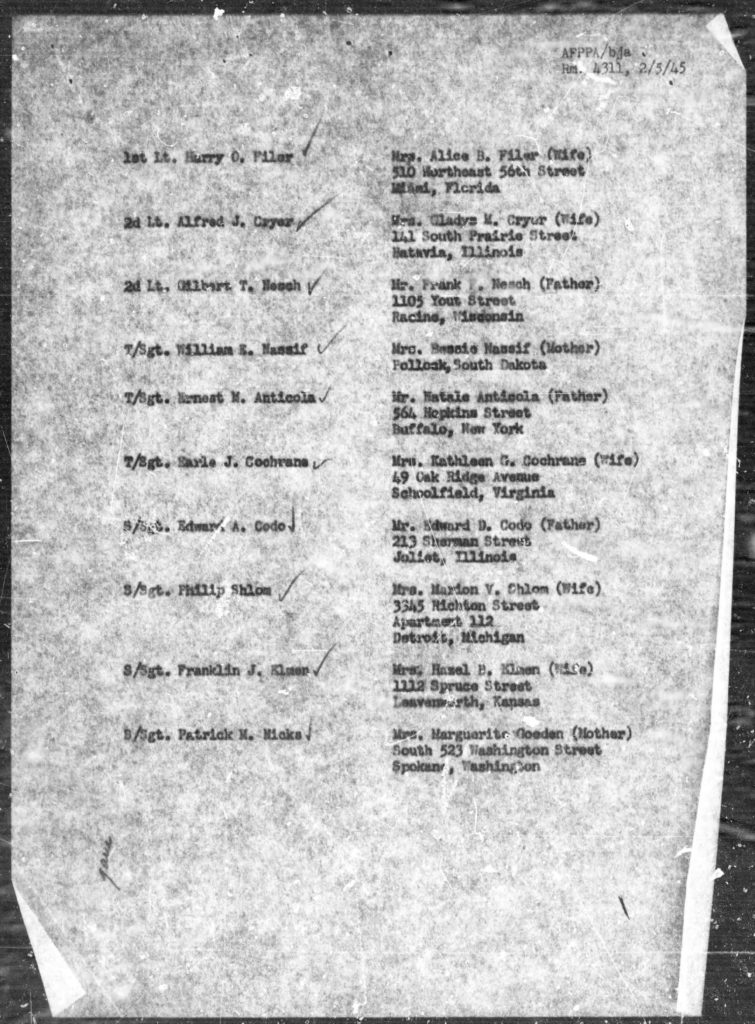

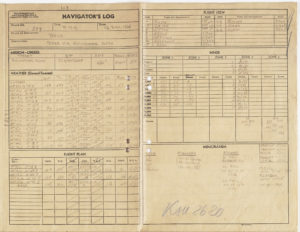

Akin to MACR 1423 for the crew of the 7th Air Force B-24D Liberator Dogpatch Express, covered in my earlier posts, “Upon An Endless Sea” and “Portraits of the Fallen: The Crew of the Dogpatch Express, in Photographs”, MACR 1087 (like many “early” (and not only “early”) Missing Aircrew Reports covering multi-place aircraft) carries neither the home addresses nor the names of the crewmens’ next-of-kin.

The men are “anonymous”; they are simply names and serial numbers, without real identities.

However, akin to the crew of Dogpatch Express, it’s been possible to “reconstruct” nominal biographical information about these men. This was done using War Department Bureau of Public Relations Press Branch Casualty List issued on 13 December, 1943 (from the United States National Archives) and especially – particularly – various databases at Ancestry.com. Using these resources, the identities of the men’s next-of-kin, and wartime places of residence could be identified.

So, briefly, this is who they were:

Pilot: Smith, Richard, F/O, T-186554

Mr. and Mrs. Albert R. [Died June 7, 1965] and Mary (Hellinger) Smith (parents), 17 Klass Ave., Buffalo, N.Y.

Mentioned in Buffalo Courier-Express December 14, 1943. Mr. Albert Smith’s obituary appeared in the same newspaper on June 10, 1965.

Co-Pilot: Newland, Otis Terrell, F/O, T-346

Born 1920, in Texas

Mr. and Mrs. Cam Alexander and Catherine C. Newland (parents), Joe L. Newland (brother), Route 3, Lone Oak, Tx.

Navigator: Chapin, Robert Dudley, Jr., 2 Lt., 0-671281

Born 1921

Lt. Cdr. and Mrs. Robert Dudley [May 20, 1876 – 1945] and Sara (Newton) [1882 – August 21, 1961] Chapin (parents); Linda Chapin [1907 – September 30, 1916] (sister), Cynthia (Chapin) Taylor (sister) [April 1, 1917 – September 12, 1982], 20 Huntington St., Hartford, Ct.

The above genealogical information about the Chapin family is by FindAGrave contributor C. Greer, whose memorial / biographical profile for 2 Lt. Chapin includes a photograph of his parents’ tombstone, on which the younger Chapin’s name is inscribed.

Due to uncertainty about copyright, I won’t display the photo “here”! Rather, you can view the image at this link.

Radio-Operator / Gunner: Anagnos, Theodore, Sgt., 32503485

Born 1914, in Oregon

Mrs. Phyllis H. Anagnos (wife), 8417 North Military Ave., Detroit, Mi.

Mr. and Mrs. Speros and Evangeline Anagnos (parents), George and Peter (brothers), 1301 Hart Ave., Detroit, Mi.

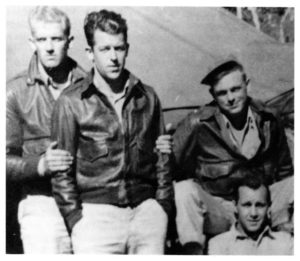

Gunner: Boykin, Johnnie Rayford, Sgt., 18121719

Born May 27, 1922, in Swenson, Texas

Mrs. Berna Dean (Stephens) Boykin (wife) (Born July 28, 1925, Mountainair, N.M. – Died November, 1982)

Johnnie Dean Boykin (son; born August 18, 1943 – died 2007) Dexter, N.M.

Mr. and Mrs. Roy Hammel and Lillian (King) Boykin (parents), Lee Roy Boykin (brother), Hagerman, N.M. / 408 W. 6th St., Roswell, N.M.

Some Observations

Born in the 1910s and 20s, they were, unsurprisingly and typically, all “young” men, with Sgt. Anagos – born in 1914 – having been the oldest.

Akin to radio operator Johnnie Boykin (yet unlike pilot Smith, co-pilot Newland, and navigator Chapin) Anagos was married.

Johnnie Boykin (assuming I’ve interpreted records at Ancestry.com correctly – well, I think I have!) became a father while overseas. His son, Johnnie Dean Boykin, was born in August of 1943. Only two and a half months old by November 3, 1943, father and son would never meet. Johnnie Dean died in 2007, while his mother, Berna Dean, passed away in 1982.

Though I have no knowledge of the numbers of sorties flown by the crew, their ranks (the pilot and co-pilot were Flight Officers) and the identical military awards received by each crew member (according to the ABMC website, each aviator was awarded the Air Medal and Purple Heart) suggest (?) that they were a relatively “new” crew, having flown – either as a unit, or individually – no more than ten combat missions.

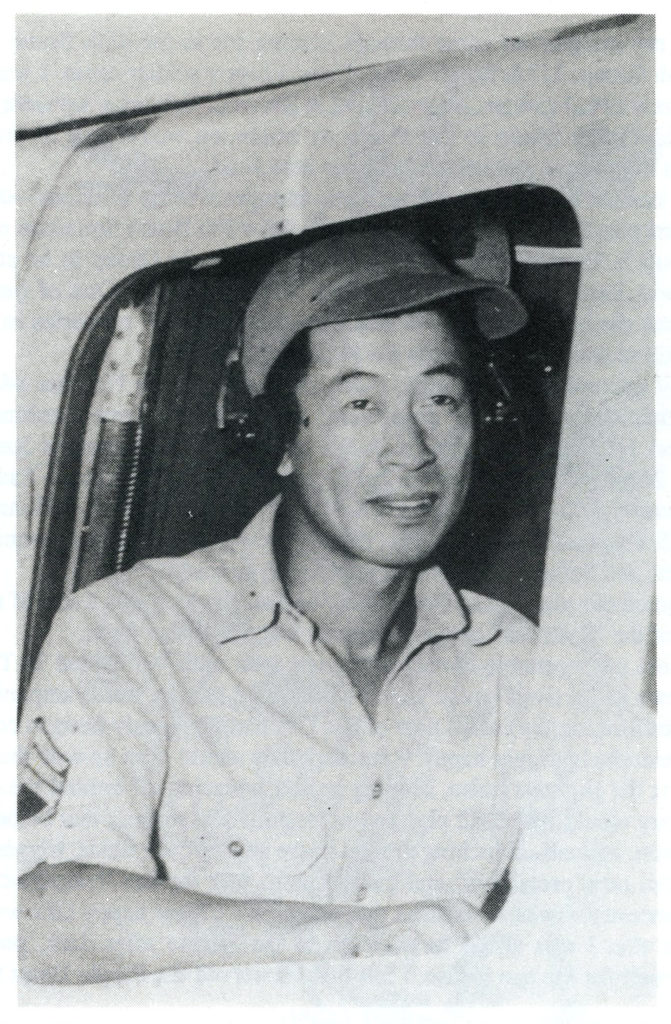

To signify that these men were more than “data”; more than mere names and serial numbers; more than statistics, here’s the one portrait I was able to find of a crew member: Sergeant Boykin. His photograph and biography are among World War Two Records of the State of New Mexico, which can be accessed at Ancestry.com.

______________________________

______________________________

The airmen’s names are memorialized on the Walls of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery in Luzon.

The ABMC website gives each man’s date death as December 15, 1945, which likely reflects a date arbitrarily established by the Army upon the closure of the postwar investigation of the crew’s fate.

______________________________

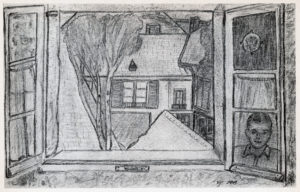

But, what of the impetus for this post – the photograph itself…?

Scanned at 1200 dpi, it’s shown below.

The image has several notable qualities.

The image has several notable qualities.

In a purely photographic sense, the picture is comprised of three “elements” that “balance” one another:

B-25G 42-64851 captured in flight, in the right center. (2)

A glassily calm sea extending to the horizon, a vague curtain of clouds suspended above, in the distance.

And both significantly and ironically, the smallest element in the image: The Smith crew, in their raft, can be seen at center left, probably headed for Bili Bili Island. Of particular note, the silhouette of the aviator on the right (it looks like he’s wearing his Mae West) is clearly distinguishable against the surface of a remarkably smooth sea.

Whether by chance, skill, or both – unfortunately, the MACR doesn’t list the photographer’s name! – the combination of composition, focus, lighting, and perspective is remarkable.

Given that neither the mainland nor the island are visible, the “direction” towards the horizon (as opposed to the direction of flight of the overlying B-25) is probably either to the north-northeast (so Bili Bili island is out of view to the “right”), or … south-southwest (thus, Bili Bili Island is out of view, to the “left”).

In this, the image is strikingly reminiscent of and similar to a photograph – below (in Lawrence Hickey’s Warpath Across the Pacific, from the Melvin L. Best collection) – showing the crew of Captain William L. Kizzire standing atop the rear fuselage of their B-25D Mitchell (41-30046 – Impatient Virgin) after their plane was ditched during a low-level attack mission to Boram Strip, near Wewak, a little over three weeks later: on November 27, 1943.

As listed at both Pacific Wrecks and Warpath, the men are:

As listed at both Pacific Wrecks and Warpath, the men are:

Pilot: Capt. William L. “Kizzy” Kizzire, 0-726787, Greybull, Wy.

Co-Pilot: 2 Lt. Charles G. Reynolds, 0-661563, Bridgeport, Oh.

Navigator: 1 Lt. Joseph W. Carroll, Jr., 0-665898, Dallas, Tx.

Flight Engineer: S/Sgt. Wilfred J. Paquette, 31127441, Northampton, Ma. (Killed while POW)

Radio Operator: S/Sgt. Roy E. Showers, Jr., 18075424, Pampa, Tx. (Killed while POW)

Gunner: S/Sgt. Fred D. Nightwine, 13085578, Slippery Rock, Pa. (Killed while POW)

Akin to members of F/O Smith’s crew, three members of Captain Kizzire’s crew – Sergeants Nightwine, Paquette, and Showers – were the subject of radio propaganda broadcasts, transcripts of which are available at Pacific Wrecks’ Radio Tokyo Broadcasts in English. (4)

______________________________

Finally, two photographs.

First, an April 2010 image of Astrolabe Bay – looking east towards the Bismarck Sea – by Jan Messersmith, from his blog Madang – Ples Bilong Mi: A Daily Journal of a Permanent Resident of Paradise. Perhaps the crews of the Sunsetters saw a vista akin to this – actually, strikingly beautiful – on the third of November in the year 1943.

Second, to close the story – though its ending will likely ever remain uncertain; it will probably never be fully “closed” – the Smith crew, in their raft, floating between the New Guinea mainland and Bili Bili Island.

Second, to close the story – though its ending will likely ever remain uncertain; it will probably never be fully “closed” – the Smith crew, in their raft, floating between the New Guinea mainland and Bili Bili Island.

I’m not in possession of Individual Deceased Personnel Files for members of the Smith crew, but considering that the definitive fate of the crew has never been established, I would suppose that those documents would offer little to resolve the men’s fate.

Well, it may be a trite expression, but it’s true: Times marches on – and it proceedes quickly.

Now 2019, only twenty-four more years remain until the year 2043. By then, a century will have transpired since the November day when crew of B-25G #850 flew into history. It would be as predumptuous as it would be naive (and probably inaccurate, to boot, though it would be intriguing!) to predict the nature of “that” world, for who in 1943 could have predicted the nature of “our” world; of 2019?

But, despite changes in technology, economics, and science, one constant will remain, and has always remained: That of human nature. And part of that nature is the need; actually very necessity, to remember the past and those who were part of it.

Notes

Notes

(1) Pvt. Smith, a soldier in the 133rd Infantry Regiment of the 34th Infantry Division, was killed in action on January 28, 1944. He is buried at the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery in Nettuno, Italy, at Grave 56, Row 10, Plot I.

(2) Well, enlarged, the serial number of the overflying B-25G seems to be 42-64851! A check of the Aviation Archeology database (unfortunately inaccessible for some time), and a hunting expedition at DuckDuckGo reveal no information about this aircraft.

Fortunately, a review of B-25s assigned to the 823rd Bomb Squadron, listed in Appendix III of Sunsetters of the Southwest Pacific, reveals the following for this aircraft: “Possibly flown overseas by 2 Lt. George J. Maturi crew. (August, 1943) Transferred to 4th Air Depot (January 8, 1944), Townsville, then to 822nd BS.” The plane is consequently listed among B-25s assigned to the 822nd Bomb Squadron, specifically on February 26, 1944. After a mid-air collision on August 1, 1944, the aircraft was transferred to the 376th Service Squadron for salvage.

In this 1200 dpi scan, the pilot is clearly visible, while the head of the gunner can be seen within the dorsal turret. Other details of the plane – such as the plexiglass tail-cone, which seems to have been strangely truncated, and open to the air – are also evident.

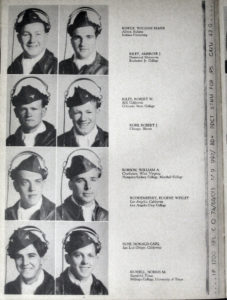

(3) The pilot of B-25D 41-30118 (Elusive Lizzie / Miss America, covered in MACR 16113) Major Cox’s was shot down during a mission to Madang on August 5, 1943. One member of his crew, S/Sgt. Raymond H. Zimmerman, was killed when the aircraft crashed. The four remaining crewmen were captured, and eventually murdered at Amron. Portraits of Major Cox and his navigator, 1 Lt. Louis J. Ritacco (from Port Chester, N.Y.) are shown below. Akin to the portrait of Lieutenant Hill, their pictures are from NARA’s “Photographic Prints of Air Cadets and Officers, Air Crew, and Notables in the History of Aviation – NARA RG 18-PU”.

(3) The pilot of B-25D 41-30118 (Elusive Lizzie / Miss America, covered in MACR 16113) Major Cox’s was shot down during a mission to Madang on August 5, 1943. One member of his crew, S/Sgt. Raymond H. Zimmerman, was killed when the aircraft crashed. The four remaining crewmen were captured, and eventually murdered at Amron. Portraits of Major Cox and his navigator, 1 Lt. Louis J. Ritacco (from Port Chester, N.Y.) are shown below. Akin to the portrait of Lieutenant Hill, their pictures are from NARA’s “Photographic Prints of Air Cadets and Officers, Air Crew, and Notables in the History of Aviation – NARA RG 18-PU”.

Flight Cadet Williston Madison Cox, Jr.

Flight Cadet Williston Madison Cox, Jr.

Cadet Louis James Ritacco

Cadet Louis James Ritacco

Major Cox’s loss is given notable attention in Garrett Middlebrook’s Air Combat At 20 Feet, the cover art of which I hope to (some day!) display in my brother blog, WordsEnvisioned, illustrating cover and interior art in books and pulp magazines from the 40s and 50s (and even more…).

(4) Of the numerous members of the 345th Bomb Group – the “Air Apaches” – who were known to have been taken captive, eight survived the war.

Listed by date of capture, they were:

McGuire, James, 1 Lt., 0-674314, Pilot (Grants Pass, Or.)

Captured March 30, 1945, while piloting B-25J 44-29350 (500th Bomb Squadron), covered in MACR 15450.

A remarkable and chilling photograph of Lt. McGuire’s B-25, on fire and diving towards Yulin Kan Bay, at the southern tip of Hainan Island, is shown below. This image, from the collection of Samuel W. Bennett (via Kevin Mahoney) appears in Lawrence Hickey’s Warpath Across the Pacific.

The latitude and longitude coordinates given for 44-29350’s loss are listed in the 500th Bomb Squadron Mission Report for the March 30 mission, as 18-10-20 N, 109-33-00 E, but they’re not given in the crew’s postwar “fill-in” MACR, which was filed on 10 April, 1946,

The latitude and longitude coordinates given for 44-29350’s loss are listed in the 500th Bomb Squadron Mission Report for the March 30 mission, as 18-10-20 N, 109-33-00 E, but they’re not given in the crew’s postwar “fill-in” MACR, which was filed on 10 April, 1946,

When plugging this location Google Maps, the location generated is about halfway between “Shendao” and “Jinmu Corner”, just off the point of land projecting west.

The 3-D aerial view below gives you a better idea of the crash location, which is identified by Google Maps’ red pointer. Intriguingly, the location (of course, the coordinates should be understood as being approximate), appears to be at the very end of a breakwater / jetty projecting west into Yulin Bay, between Shendao and Jinmu Corner.

The 3-D aerial view below gives you a better idea of the crash location, which is identified by Google Maps’ red pointer. Intriguingly, the location (of course, the coordinates should be understood as being approximate), appears to be at the very end of a breakwater / jetty projecting west into Yulin Bay, between Shendao and Jinmu Corner.

Here’s a closer 3-D view…

Here’s a closer 3-D view…

The elevated terrain to the west of the “Yalong Bay National Tourism Holiday Resort” (the dark color of terrain, compared to the light-colored low-lying terrain just to its west, may simply be an artifact of image processing) might correspond to the ridge visible behind the descending B-25, in the Bennett collection photo shown above.

The elevated terrain to the west of the “Yalong Bay National Tourism Holiday Resort” (the dark color of terrain, compared to the light-colored low-lying terrain just to its west, may simply be an artifact of image processing) might correspond to the ridge visible behind the descending B-25, in the Bennett collection photo shown above.

Finally, for completeness, here’s a map of Hainan Island…

________________

________________

Lawlis, Merritt E., Capt., 0-432168, Navigator (Indianapolis, In.)

Muller, Benjamin T., S/Sgt., 18090388, Radio Operator (El Paso, Tx.)

Captured April 3, 1945. Crew members of 1 Lt. William P. Simpson, from B-25J 43-27888 “Pensive” (500th Bomb Squadron), covered in MACR 14225.

________________

Shott, John, Cpl., 33421756, Tail Gunner (Aliquippa, Pa.)

Captured May 17, 1945. Crew member of 2 Lt. James T. Lackey, from B-25J 44-30164 (500th Bomb Squadron), covered in MACR 14447.

________________

Hart, Ted U., 2 Lt., Oak Park, Il., 0-771709, Pilot (Oak Park, Il.)

Gatewood, Henry, 2 Lt., 0-812542, Co-Pilot (Holly Springs, Ms.)

Ehlers, Karl L., 2 Lt., 0-1017008, Navigator (Niagara Falls, N.Y.)

Beck, Theron Kenneth, Cpl., 15364114, Radio Operator (Louisville, Ky.)

Captured May 27, 1945. Aircraft B-25J 44-28152 “Apache Princess”, (501st Bomb Squadron), covered in MACR 14524.

______________________________

A Digression: Missing Air Crew Reports and the Destiny of Historical Documentation

The historical importance of Missing Air Crew Reports has been apparent since the declassification of these records in the 1980s. Though obviously of central use in resolving the fate of missing WW II Army Air Force personnel, the information in these reports extends to areas as military technology, aerial combat tactics, air-sea rescue, outdoor survival (in all manner of terrains and climates), escape and evasion, the experiences of POWs, war crimes, and even in a subtle way – perhaps inevitably, though indirectly – the postwar readjustment of veterans and military casualties to civilian life, and genealogy.

As presented in my earlier post, The Missing Photos: Photographic Images in Missing Air Crew Reports, I was very fortunate in 2014 to have had the opportunity to examine Missing Air Crew Reports in their “original” physical – print – format, ultimately making digital copies of a small number of these documents: specifically, those MACRs which include photographs.

Having first learned about MACRS in the mid-1980s, this was a marked change from the way I’d previously accessed and studied these documents. That effort was first done using microfiche copies purchased from NARA, next through visits to the National Archives in College Park, and finally, in digital format, via Fold3.

It was through latter format that I conducted the bulk of my research into these documents. Ironically, though the nominal ability to access and study MACRs via Fold3 has been extraordinarily convenient (and hey, fewer road trips via I-95 – ugh! – to College Park) and productive (searching by MACR number, surname, or aircraft serial number is extremely useful), I discovered that the potential value of digitized MACRs on Fold3 is severely hampered by the quality of images of the MACRs, and, the design of the Fold3 MACR database.

This problem was described by aviation historian Frank J. Olynyk in a 2012 post at the 12oclockhigh forum, which is worth reading in detail.

I can verify Mr. Olynyk’s observations.

As he described, many Missing Aircrew Reports,are simply; completely absent from Fold3. (An example: Try searching for MACRs 3500 and 3631, for B-24H 42-95064 (464th BG, 778th BS) piloted by 2 Lt. Edward J. Barres, or, search by the bomber’s serial number. Good luuuck…!) This is even true for reports far “higher” in the numerical sequence of the documents than the mid-3000 range.

In addition, the quality of some scans, primarily among low-numbered MACRs (and even among some higher numbered MACRs) is extremely poor – sometimes so much as to render some digitized MACRs to be, well, er, uh…useless.

This is particularly ironic in light of Fold3’s company history, which states, “The concept for Fold3 is rooted in the company’s years of experience in the digitization business as iArchives, Inc. Starting in 1999, iArchives digitized historical newspapers and other archive content for leading universities, libraries and media companies across the United States.

From the beginning, the iArchives team developed a unique understanding of the value of creating an online repository for the world’s original source documents. Leveraging the proprietary systems and patented processes built for the digitization of paper, microfilm and microfiche collections, the management team made a strategic decision: Use the iArchives platform to provide access to these historically significant and valuable collections.”

Uh? Okay.

Conjecture: These problems seem to have resulted from two factors.

First, the primary source material seems to have been the fiche version of the MACRs, rather than the original documents themselves.

Second, perhaps the low-numbered documents (er … um … I mean fiche) comprised the start of the learning curve by which the processors (who? where? when? how?) became familiar with procedures for digitization. If so, once digitizing and data entry had been systemized, any poor quality scans eventuating from the initial efforts at scanning – of low-numbered MACRs – were never replaced by a “second round” of suitable, better quality images. Similarly, errors or gaps from the processing of higher-numbered MACRs were likewise not corrected.

(Admittedly, conjecture on my part.)

What’s not uncertain is the potential – in terms of ease of searchability and quality of both images and information – that could have resulted from a better-designed and implemented effort at document processing and scanning. Given what I observed of the physical quality of the original MACRs (they’ve held up very well over nearly eight decades) the original documents could have been (carefully; conscientiously) scanned at high resolution, and, in color. Paralleling this, the database by which the MACRs are accessed could have been designed with an altogether different primary key (as per Mr. Olynyk’s suggestion), or, multiple primary keys.

In this, I’m reminded of the database of the National Archives of Australia, or that of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, which in terms of aesthetic design, ease of use, presentation of results to the user, and quality of digital files, are very, very (very) impressive.

While obviously Fold3’s MACR collection is only one of numerous repositories of digital documents available through that website (owned by Ancestry.com since 2010), not a stand-alone collection with a dedicated website, the potential held for something much better.

In summary, though this digital resource is certainly valuable and useful, it is absolutely nowhere near what it could have been – in terms of quality, usability, and accuracy – had the design and creation of the product really been undergirded by measures of thought, planning, and quality control.

References

Books

Grover, Roy C., Incidents in the Life of a B-25 Pilot, AuthorHouse, October 19, 2006

Hickey, Lawrence J.; Janko, Mark M.; Goldberg, Stuart W., and Tagaya, Osamu, Sun Setters of the Southwest Pacific Area – From Australia to Japan: An Illustrated History of the 38th Bombardment Group (m), 5th Air Force, World War II – 1941-1946, As Told and Photographed by the Men Who Were There, International Historical Research Associates, Boulder, Co. (and) The 38th Bomb Group Association – (or) Albert A. Kennedy, Sr. (or) David Gunn, 2011

Hickey, Lawrence J., Warpath Across the Pacific: The Illustrated History of the 345th Bombardment Group During World War II, International Research and Publishing Corporation, Boulder, Co., 1984

Maurer Maurer, Air Force Combat Units of World War Two, Office of Air Force History, Washington, D.C. (Reprint from United States Government Printing Office, 1961), 1983

Middlebrook, Garrett, Air Combat At 20 Feet – Selected Missions From A Strafer Pilot’s Diary (A World War II Autobiography), Garrett Middlebrook, Fort Worth, Tx., 1989

“Message From the Front” – Japanese Radio Broadcasts from Tokyo to Western United States. Transcript within Records of the Foreign Broadcast Intelligence Service

Aircraft Histories

B-25D 41-30018, at Pacific Wrecks

B-25G 42-64850, at Pacific Wrecks

Aviation Archeology

38th Bomb Group

38th Bomb Group

823rd Bomb Squadron, 38th Bomb Group

Missing in Action and Prisoners of War

Tunnel Hill Massacre

Japanese Military Installation at Amron, New Guinea

POWs at Amron, New Guinea

United States Defense POW / MIA Accounting Agency

Australian War Memorial

Alexishafen, New Guinea, Central Interpretation Unit (C.I.U.) Maps, at Australian War Memorial

United States National Archives

Records of the Foreign Broadcast Intelligence Service

Records Group 262, Entry 3, 530/17/11-13/00, Box 699.

War Department Bureau of Public Relations Press Branch Casualty Lists of 13 December, 1943