The world we live in is, by nature, unpredictable. Some events appear – by all standards of understanding and reason – to present us with seemingly irrevocable and misfortune and challenge. Other situations and experiences can carry us – by all measures of sense and logic – to a horizon of apparently good fortune. But then, in time, what appears to have been misfortune may actually – albeit unknown to us, at the time – be a reprieve and “second chance”, while what seems to have been bountiful luck may – in a way of which we are comfortably unaware – presage a much more dire outcome.

If this is so during “conventional” times, then vastly more so during a time of war, when the pace, sweep, and nature of events – and the danger inherent to those events – is magnified many fold.

Some 75 years ago, such a situation transpired in the life of the pilot of a B-24 Liberator bomber.

But first, an explanation.

______________________________

In March and April of 2017, I created two blog posts concerning photographs I’d discovered at the United States National Archives in MACR (Missing Air Crew Report) number 1423. This MACR covers the loss of a B-24D Liberator (41-24214 – Dogpatch Express) of the 11th Bomb Group’s 42nd Bomb Squadron, over the Central Pacific Ocean, after a mission to the atoll of Taroa Island, in the Maloelap Atoll of the Marshall Islands, on December 21, 1943.

A particular image appearing in the “first” post is a very high resolution (2400 dpi) cropped scan of one of the photographs, showing the damaged bomber shortly before it crashed into the sea…

The “second” blog post includes an image accompanying the FindAGrave biographical profile of T/Sgt. Roy T. Gearon, the bomber’s radio operator, via FindAGrave contributor Patrick Maher, Sgt. Gearon’s cousin. The picture shows most of the ill-fated bomber’s crew, as they appeared some months prior to the December twenty-first mission. The image is captioned: “Roy’s crew picture taken a few months before they were shot down. T/Sgt. Roy Thomas Gearon bottom left.” While T/Sgt. Gearon’s FindAGrave profile gives no further information about this image, in light of recently acquired information and photographs (see much more below…), it’s seen that T/Sgt. Gearon is at the far left, standing.

The “second” blog post includes an image accompanying the FindAGrave biographical profile of T/Sgt. Roy T. Gearon, the bomber’s radio operator, via FindAGrave contributor Patrick Maher, Sgt. Gearon’s cousin. The picture shows most of the ill-fated bomber’s crew, as they appeared some months prior to the December twenty-first mission. The image is captioned: “Roy’s crew picture taken a few months before they were shot down. T/Sgt. Roy Thomas Gearon bottom left.” While T/Sgt. Gearon’s FindAGrave profile gives no further information about this image, in light of recently acquired information and photographs (see much more below…), it’s seen that T/Sgt. Gearon is at the far left, standing.

Though my prior posts list the names of the plane’s crew members (from MACR 1423 – the first sheet is below), in the absence of other information it was then impossible to attach “names to faces”.

Though my prior posts list the names of the plane’s crew members (from MACR 1423 – the first sheet is below), in the absence of other information it was then impossible to attach “names to faces”.

Thus, the men in the photograph remained, in senses both symbolic and very real, “unknown”.

Thus, the men in the photograph remained, in senses both symbolic and very real, “unknown”.

______________________________

Well, time passes.

Sometimes; all too often (especially in the world of 2018) time can drape a veil of forgetfulness over history.

But, on occasion, the passage of time can actually bring the past into clarity, memory, and awareness. Fortunately, such has happened with the names of the crewmen of Dogpatch Express.

Recently, I was contacted by Richard “Rich” Thomspon, Jr., through whom I learned that the officer in the center of the above photo – the fellow seated in the wheelchair – was his father, Second Lieutenant Richard (“Dick”) Sydney Thomspon, Sr. At the time the image was taken, Dick, severely wounded during the 11th Bomb Group’s mission to Wake Island, on July 24, 1943, was recovering from his injuries, probably at Oahu, Hawaii. As indicated by Roy Gearon’s FindAGrave biography, Dick indeed was being visited by his crewmen.

All but two of the men in the photo – aboard Dogpatch Express five months later – would not survive the war.

Rich has created a detailed, profusely illustrated, and well-written account of his father’s military experiences and postwar life, entitled Wicked Witch, which he has kindly shared with me. A few of the many evocative images from this document appear below.

As a result, through Rich’s assistance and enthusiasm, I’m now able to “attach” names to faces, and, casting aside time’s anonymity, definitively identify each airman. The mens’ identities have thus become more than the nominal information – “name, serial number, and next of kin” – typical of Missing Air Crew Reports and Casualty Lists.

______________________________

Dick Thompson was born in Boston on December 9, 1918. His family eventually moved to Pennsylvania, residing at 25 Rolling Road in West Park Station, a suburb of Carrol Park, near Philadelphia’s Overbrook Park section.

Dick entered the military in 1941 (prior to which time he’d been an iron-worker), before Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. He was eventually assigned to the “22nd Military Police” of the 1st Armored Division, and was stationed in Louisiana.

In time – though the details and specific dates are unknown – Dick entered the Army Air Force. Having completed training as an Aviation Cadet, he was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant on the 12th of December (Saturday), 1942. The other significant – if not greater – transition in his life was his marriage the next day to Elizabeth Marie McCaffrey, of Philadelphia.

In time – though the details and specific dates are unknown – Dick entered the Army Air Force. Having completed training as an Aviation Cadet, he was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant on the 12th of December (Saturday), 1942. The other significant – if not greater – transition in his life was his marriage the next day to Elizabeth Marie McCaffrey, of Philadelphia.

Though the details are unknown, Dick spent the Winter and Spring of 1943 doing further training in the southwestern United States. According to Rich, it’s unknown, “…when his crew was assigned or how much stateside “bonding” they got in before leaving for Hawaii.”

In any event, his crew initially – almost certainly – consisted of:

2 Lt. John E. Lowry, Jr. – co-pilot

2 Lt. Carl A. “Mort” Mortenson – navigator

Lt. Lori – bombardier

Technical Sergeant Clarence T. Sopko – Flight Engineer

Staff Sergeant Arnold J. Paradise – Radio Operator

Staff Sergeant Carl N. Dell – gunner

Staff Sergeant Earl D. Neilsen – gunner

Sergeant Del Vickio (spelling uncertain – could be “Del Vechio”, or, “Del Vecchio”) – gunner

Rich notes that each of the enlisted men wore at least four sergeant’s stripes, indicating that they may well have accrued more service time than their own four officers. The crew eventually arrived at Kualoa, Hawaii (specific date unknown – probably mid-June), where they were assigned to the 11th Bomb Group’s (the “Grey Geese”) 42nd Bomb Squadron.

On June 16, 1943, they flew aircraft 42-20688, the WICKED WITCH, as verified from data at the Oak Trust Library. Lt. George W. Smith, who would pilot the ill-fated DOGPATCH EXPRESS six months later, is known to have piloted the WITCH earlier – on June 7 – for a test of the plane’s automatic flight control equipment.

The 11th Bomb Group’s second combat mission since June of 1942 (the first having been a bombing and photo reconnaissance mission, staged from Funafuti (in the Ellice Island Group) to Makin and the Jaluit Islands), scheduled for July 24, 1943, was to be to Wake Island. For this purpose, the 11th staged at Fongafele Island, at Funafuti. Prior to that time the 11th Bomb Group was engaged in organizing itself as a combat organization, and, flying practice and patrol missions around the Hawaiian Islands.

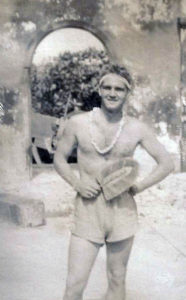

Here’s an image of Dick having briefly “gone native” near the Funafuti Island church…

The July 24 mission would be Dick’s first opportunity to fly the WITCH since June 16. As noted by Rich (via historian Bob Livingstone of Brisbane, a member of the Aviation Historical Society of Australia and author of two books on the B-24), “…when a new crew came in with a new plane, the other air crews would “seize” their plane and give the new crew one of the ratty old planes that was pretty well used up. Hard to argue after seeing what happened to the “WITCH” as it did 6 missions in the 5 weeks dad was there but with Lieutenants Deasy, Stay, and Sands.” (In the time intervening since his arrival, Dick had piloted 9 other B-24s on a total of 18 missions.) Rich has also suggested that the allocation of new planes to veteran crews was, “…part of the training for a new crew. If they just got to fly a new plane all the time, they would likely as not have any mechanical issues to deal with. … Flying the older planes, especially during training and sea search missions would give them a chance to think and interact as a team trying to survive under extenuating circumstances. I think this was all by design of the bomb group commander, Colonel William J. Holzapfel, Jr., At this point in the war, he was responsible to ensure his airman were trained in the skills to win the war and he was learning right along with his air crews.”

The July 24 mission would be Dick’s first opportunity to fly the WITCH since June 16. As noted by Rich (via historian Bob Livingstone of Brisbane, a member of the Aviation Historical Society of Australia and author of two books on the B-24), “…when a new crew came in with a new plane, the other air crews would “seize” their plane and give the new crew one of the ratty old planes that was pretty well used up. Hard to argue after seeing what happened to the “WITCH” as it did 6 missions in the 5 weeks dad was there but with Lieutenants Deasy, Stay, and Sands.” (In the time intervening since his arrival, Dick had piloted 9 other B-24s on a total of 18 missions.) Rich has also suggested that the allocation of new planes to veteran crews was, “…part of the training for a new crew. If they just got to fly a new plane all the time, they would likely as not have any mechanical issues to deal with. … Flying the older planes, especially during training and sea search missions would give them a chance to think and interact as a team trying to survive under extenuating circumstances. I think this was all by design of the bomb group commander, Colonel William J. Holzapfel, Jr., At this point in the war, he was responsible to ensure his airman were trained in the skills to win the war and he was learning right along with his air crews.”

As noted by Richard, “in terms of aerial warfare, [the mission to Wake Island] was just one more mission with nothing to distinguish it from others. Conducted by Liberators of the reconstituted 11th, it was a “nuisance raid” ordered by the navy to relieve pressure in the South Pacific and to confuse the enemy as to where the next blow would fall.”

“12 planes were scheduled, 10 took off and eight went over the target to drop seven 500 pound general purpose bombs, 55 fragmentation bomb clusters and three 650 pound depth charges. Hits were scored on Wake’s oil storage areas, barracks and a gun emplacement.”

“When Lt. Richard Thompson’s WICKED WITCH got to Midway from Hawaii to stage for the Wake raid, their tail gunner, S/Sgt. Earl D. Nielsen, required an emergency appendectomy. When … Colonel Holzapfel asked the Marines for a replacement, there were more than 200 volunteers. So, the name of Sgt. William C. Campbell was drawn out of the hat. A Marine Captain offered $1,000 to take the Sergeant’s place, but was refused and Sgt. Campbell took over the tail guns of WICKED WITCH and over Wake, he downed a Zero. (The eight-plane raid claimed nine Zeroes destroyed, four probable and three damaged.)”

The Wake Island mission cost the 11th Bomb Group two B-24s and twelve airmen.

One aircraft, B-24D 42-40676 (Cabin in the Sky), piloted by First Lieutenant James R. Cason, was struck in the port fin and rudder by a Zero (whether accidentally or deliberately will remain unknown), crashing into the sea with no survivors. The plane’s loss is covered in Missing Air Crew Report 314.

Lieutenant Richard W. Lipman, whose detailed, frank, and often moving diary (encompassing November, 1942, through December, 1944) appears in Grey Geese Calling, recorded that, “Cason had his rear stabilizer rammed by a Zero and he spiraled down shooting all the way to explode upon hitting the water. I don’t know but I can’t seem to swallow the fact that the guys I know so well and the ship I flew in from Kualoa to Midway are gone forever. Clean cut Cason, good natured Thompson, “Slick” Moore, McConnell and Kane [?] just out of Cadets. Man, this ain’t for me!”

Along with Cason, the plane’s crew comprised:

1 Lt. Loren E. Thompson – Co-Pilot (Nehama County, Nebraska)

2 Lt. Robert B. McConnell – Navigator (Multnomah County, Oregon)

2 Lt. Ernest W. Moore – Bombardier (Anderson County, South Carolina)

T/Sgt. Lee R. Sterner – Flight Engineer (Muscatine County, Iowa)

S/Sgt. Lloyd R. Taylor – Radio Operator (Wilson County, Kansas)

S/Sgt. James W. Strope – Gunner (Chicago, Illinois)

Sgt. Louis N. Lane – Gunner (Lenawee County, Michigan)

S/Sgt. Harlan G. Davis – Gunner (Harrison County, West Virginia)

Sgt. Robert O. Stephens – Gunner (Los Angeles, California)

Cpl. Walter F. Kowalski – Photographer (Lackawanna County, Pennsylvania)

Here’s a photograph of eight members of James Cason’s crew, reportedly taken a few hours before this mission, from Cason’s FindAGrave biographical profile, provided by contributor Terry Woodward. The image comes from the scrapbook of Bill Morrison. Unfortunately, no names – “who is who?” – are listed.

…and, also from Bill Morrison’s scrapbook, we find an image of Lt. Cason, as seen in Hawaii in the summer of 1943 (also contributed by Terry Woodward):

…and, also from Bill Morrison’s scrapbook, we find an image of Lt. Cason, as seen in Hawaii in the summer of 1943 (also contributed by Terry Woodward):

Aboard another B-24D, 41-23983, 1 Lt. Joseph A. Gall’s Daisy Mae, two crew members were killed and two wounded during attacks by Zero fighters. Lt. Gall and F/O Van Horn crash-landed their bomber at Sand Island, one of the three islands comprising the Midway Atoll (the others are Eastern and Spit Islands).

Aboard another B-24D, 41-23983, 1 Lt. Joseph A. Gall’s Daisy Mae, two crew members were killed and two wounded during attacks by Zero fighters. Lt. Gall and F/O Van Horn crash-landed their bomber at Sand Island, one of the three islands comprising the Midway Atoll (the others are Eastern and Spit Islands).

Included in Lt. Gall’s crew were:

F/O John N. Van Horn – Co-Pilot

2 Lt. Benjamin I. Weiss – Navigator – Wounded

2 Lt. Myron W. Jensen – Bombardier – Died of Wounds (Douglas County, Nebraska)

S/Sgt. Arvid B. Ambur – Flight Engineer / Waist Gunner – Wounded

T/Sgt. Thomas Wyckoff – Top Turret Gunner – Wounded

S/Sgt. Robert L. Patterson – Radio Operator / Waist Gunner

S/Sgt. Francis J. Perkins, Jr. – Gunner

S/Sgt. Robert B. Storts – Nose Gunner

S/Sgt. Earl W. Conley – Tail Gunner

Sgt. Joseph P. Evans – Photographer – Killed in Action (Tom Green County, Texas)

As described by Lt. Lipman, “Gall got shot up plenty. His ship I mean. Jenson [sic] got hit in the gut, shoulder and wrist – has a 50-50 chance of living. Sgt. Evans, photographer, got a gut wound and died before returning. There were 2 other injuries on board. There were 200 holes in “Daisy Mae”. I went over and saw it where Gall pulled to a stop on its nose 2 inches from the ocean at the end of the runway. He came in with 3 engines and no brakes.”

Here’s a view of the Midway Atoll taken on November 24, 1941, 14 days before December 7, 1941. (Image 80-G-451086) Eastern Island is in the foreground, and Sand Island is across the entrance channel, in the center background.

These two images, from B-24 Best Web, show Daisy Mae after her crash-landing, at the water’s edge. Not visible in the lower photograph is the presence of a nose turret (a grafted-on B-24 tail turret) which replaced the bombardier’s “birdcage” typical of B-24Ds.

These two images, from B-24 Best Web, show Daisy Mae after her crash-landing, at the water’s edge. Not visible in the lower photograph is the presence of a nose turret (a grafted-on B-24 tail turret) which replaced the bombardier’s “birdcage” typical of B-24Ds.

Lt. Jensen’s obituary, from his FindAGrave biographical profile, (contributed by Loren Bender) appears below:

Lt. Jensen’s obituary, from his FindAGrave biographical profile, (contributed by Loren Bender) appears below:

Despite Daisy Mae’s return, Lt. Jensen’s name is commemorated on the Courts of the Missing at the Honolulu Memorial. Quite strangely, it appears that he has no actual grave.

Despite Daisy Mae’s return, Lt. Jensen’s name is commemorated on the Courts of the Missing at the Honolulu Memorial. Quite strangely, it appears that he has no actual grave.

______________________________

And, aboard the WICKED WITCH?

During the attack by intercepting Zero fighters, the aircraft was struck by a projectile which penetrated the left forward fuselage, directly through the location of the painted WITCH’s left arm. (See photo below.) The shell penetrated Dick’s calf left leg and thigh, the pain and loss of blood rendering him unconscious. According to bombardier Lt. Thrasher, another projectile entered the WITCH in front of the nose wheel, passing between his legs and knocking him away from his bombsight.

Lieutenant John Lowry, Dick’s co-pilot, took control of the aircraft, bringing it safely back to Funafuti. After repairs, the WITCH would bear the symbol of one Japanese flag, for the Zero shot down by Sgt. Campbell.

Lt. Thrasher described both projectiles as having been 20mm cannon shells (from the Zeros fighters’ Type 99-1 cannon). Though it’s a point of conjecture, given the destructive explosive power of such shells and the evident (fortunate!) seeming absence of a actual explosions within the aircraft, I wonder if the plane was actually struck by .303 machine-gun bullets. Just an idea. If so, this would be consistent with a letter of 30 July sent to Dick’s wife from Adjutant General J.A. Ulio, which specifically states that, “Lieutenant Thompson sustained gunshot wounds…”

______________________________

This photo, taken some months before the July mission, shows Dick in the cockpit of the WITCH. Note the name “BETTINA” – evidently inspired by the name of his wife, Betty – below the cockpit. A name (“MUGGSIE”) also appeared under the co-pilot’s window, possibly the nickname of John Lowry’s wife, Margaret.

______________________________

______________________________

The WITCH was destroyed during a Japanese air raid on Funafuti on November 17, 1943, her incinerated remains being the subject of Army Air Force photos 62903AC / 3A43074 and B-62903AC / A43076, shown below, respectively. While most of the plane has been reduced to aluminum cinders, some parts, such as engines, oxygen bottles, landing gear wheel hubs, the supporting truss for the Sperry ball turret, machine guns, as well as belts of .50 caliber ammunition, are identifiable.

With the demise of the WITCH, Dick’s crew were assigned to the DOGPATCH EXPRESS, the subject of the two prior posts.

______________________________

______________________________

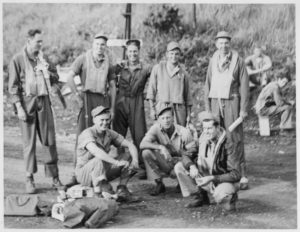

The following three photos, via Rich, show Dick being visited by his crew at Oahu. The men were identified through communication with Rich, and, a close examination the these images. Along with Dick, two men in the photo – (Lt. Jim Thrasher, the bombardier, and Sgt. Larson, a gunner) were not aboard the DOGPATCH EXPRESS on December 21.

So, at last and at least, we finally know “who” they are…

______________________________

This “first” picture is identical to the crew photo appearing at Sgt. Roy Gearon’s FindAGrave biographical profile, albeit of much higher resolution. The men are, left to right:

Front row (kneeling):

T/Sgt. Clarence T. Sopko, gunner

Sgt. Larson (first name unknown) – gunner

S/Sgt. Carl N. Dell – tail gunner

Rear row (standing)

T/Sgt. Roy T. Gearon – Radio Operator

S/Sgt. Earl D. Nielsen – waist gunner

2 Lt. Carl. A. “Mort” Mortenson – navigator

Lt. Jim Thrasher – bombardier

S/Sgt. Arnold J. Paradise – gunner / radio operator

2 Lt. John E. “Jack” Lowry, Jr. – co-pilot

______________________________

______________________________

In the picture below, the men have shifted positions. Given that all crew members are visible in the image, the picture must have been taken by an anonymous photographer “behind the camera”, perhaps a member of the hospital staff.

All are standing behind Dick, while S/Sgt. Earl D. Nielsen is kneeling in the front. The men are (left to right):

Sgt. Larson

T/Sgt. Clarence T. Sopko

T/Sgt. Roy T. Gearon

2 Lt. Carl. A. “Mort” Mortenson

Lt. Jim Thrasher

S/Sgt. Arnold J. Paradise

2 Lt. John E. “Jack” Lowry, Jr.

S/Sgt. Carl N. Dell

______________________________

______________________________

Here’s a superb photo of the crew’s officer’s. Behind Dick stand:

Lt. Jim Thrasher

(Further information about Lt. Thrasher is unknown)

2 Lt. Carl. A. “Mort” Mortenson, 0-738872, Navigator

Mr. Harry Walter Mortenson (brother), 1380 Riverside Drive, Lakewood, Oh.

2 Lt. John E. “Jack” Lowry, Jr., 0-800907, Co-Pilot

Mrs. Margaret E. Lowry, Jr. (wife), Spring St., Smyrna, Ga.

Along with the loss of the Cason and Gall crews, Lt. Lipman made note of Dick’s injury, and, Lt. Lowry’s return of the plane to Midway: “Dick Thompson was wounded in the leg at several places and by now he’s probably back at Oahu via an LB-30. It was only a miracle that Lowry was able to land that one OK and on Midway instead of 200 miles out.”

Along with the loss of the Cason and Gall crews, Lt. Lipman made note of Dick’s injury, and, Lt. Lowry’s return of the plane to Midway: “Dick Thompson was wounded in the leg at several places and by now he’s probably back at Oahu via an LB-30. It was only a miracle that Lowry was able to land that one OK and on Midway instead of 200 miles out.”

______________________________

First Lieutenants George W. Smith and Ralph P. Ortiz, the pilot and bombardier of DOGPATCH EXPRESS on December 21, do not appear in these photos. As such, they were almost certainly shifted from other crews to “fill-in” for Dick and Lt. Jim Thrasher on that date, with Lt. Smith perhaps “taking over” for Dick’s crew after the latter’s July 24 injury. Smith’s receipt of the Air Medal and Purple Heart, and Ortiz’ receipt of the Air Medal, two Oak Leaf Clusters, and Purple Heart, would suggest that they respectively completed from five to ten, and fifteen to twenty, combat missions, prior to December 21.

However, it is known that Smith had been injured almost six months previously. As recorded for June 14, 1943, by Lieutenant Lipman, “Well here’s the big story. Today 3 of our ships were to take off for an important photographic mission in the S.W. Pacific. All three were terrifically loaded down – the first two used every foot of the runway and barely cleared the trees then came #3 with me right alongside the runway in a jeep. About half-way down the runway its nose went down and it skidded for about 100 yards till it swerved off onto the highway. Two of its propellers flying off onto the adjacent beach. Well I can tell you that I spotted my underwear then and there. My first thought was to speed over there to see if I could help any of the crew to get out of the plane or to get to the hospital and off I flew in the jeep towards the plane about when I was 50 feet away flames broke out in engine #2 and off I went in the opposite direction only this time twice as fast because the uncomfortable vision of exploding hi-octane gas and exploding ammunition appeared in my mind.

The fire was put out, however, and the only person really hurt was Smith, the pilot, whose arm was quite smashed by a flying propeller.

Man some experience! I took a lot of pictures but Capt. Peairs of S-2 is going to see them – I hope to get them back.”

______________________________

Dick’s wartime scrapbook includes images of his crew’s enlisted men, possibly taken while his crew was undergoing training in the United States. (Further information may – ?- be forthcoming.) Fortunately, Dick had the foresight to record the names of each enlisted man below that man’s individual portrait.

That scrapbook page, which includes a group photo of the enlisted men, is shown below.

In this group photo, the men are (left to right):

In this group photo, the men are (left to right):

S/Sgt. Carl N. Dell

S/Sgt. Carl N. Dell

Sgt. Del Vickio (“Del Vechio” – “Del Vecchio”?)

S/Sgt. Earl D. Neilsen

T/Sgt. Clarence T. Sopko

S/Sgt. Arnold J. Paradise

The men’s individual portraits follow…

______________________________

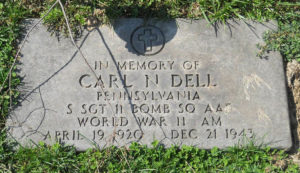

S/Sgt. Carl N. Dell, 13038323, Gunner

Born 4/19/20

Born 4/19/20

Mr. William J. Dell (father), Route 1, Middle Road, Pittsburgh, Pa.

Memorial Tombstone at Saint Mary’s Cemetery, Pittsburgh, Pa. (Photo by “Genealogy-Detective”)

______________________________

______________________________

Sgt. Del Vickio (“Del Vechio” – “Del Vecchio”?)

Like Lt. Thrasher and Sgt. Larson, Sgt. Del Vickio was also not a member of the Dogpatch Express crew on December 21.

Like Lt. Thrasher and Sgt. Larson, Sgt. Del Vickio was also not a member of the Dogpatch Express crew on December 21.

______________________________

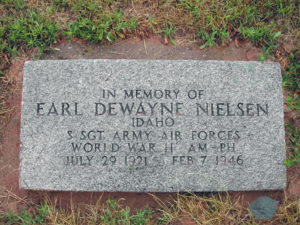

S/Sgt. Earl Dewayne Nielsen, 39831608, Gunner (Tail Gunner?)

Born 7/29/21, Thatcher, Idaho

Born 7/29/21, Thatcher, Idaho

Mr. and Mrs. Albert (6/5/91 – 2/3/65) and Vera Charlotte (Panter) Nielsen (9/1/97 – 5/11/68) (parents); Albert, Earl, Phyllis, and Wilda (brothers and sisters)

Cleveland, Idaho

Memorial Tombstone at Cleveland Cemetery, Franklin County, Idaho (Photo by Bill E. Doman) Note that the tombstone does not carry the actual date of his death. This date, identical to that appearing on the website of the American Battle Monuments Commission, probably represents the date on which he was declared dead for legal purposes, according to Section 5 of Public Law 490. Such date discrepancies can be found for many servicemen still missing from the Second World War, particularly still-missing airmen and naval personnel who were casualties in the Pacific Theater and Asia. (And sometimes, Europe as well.)

Here are two portraits of Sgt. Nielsen. The first, uploaded by Dianne Roberts to his FindAGrave biographical profile, and the second, at the Nielsen family tree, at Ancestors Family Search.

Here are two portraits of Sgt. Nielsen. The first, uploaded by Dianne Roberts to his FindAGrave biographical profile, and the second, at the Nielsen family tree, at Ancestors Family Search.

______________________________

______________________________

T/Sgt. Clarence T. Sopko, 35308715, Flight Engineer

Born 1/22/20

Born 1/22/20

Mrs. Mary S. Sopko (mother), 2138 West 26th St., Cleveland, Oh.

Memorial Tombstone at Ohio Western Reserve National Cemetery – Section M, Plot 6 (Photo by Douglas King)

______________________________

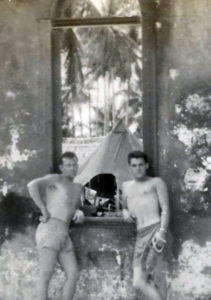

S/Sgt. Arnold J. Paradise, 36264577, Gunner

Mrs. Fern Paradise (mother), Garden Acres, Chippewa Falls, Wi.

WW II Memorial – June Havel (sister)

From Dick’s album, here’s a picture of Sergeants Dell and Paradise at the native church on Funafuti, around the time of the 11th’s mission to Makin and Jaluit. They seem to have “gone native”, like their pilot, Dick.

______________________________

______________________________

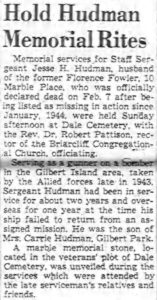

S/Sgt. Jesse Harvey Hudman, S/Sgt., 12146959, Assistant Engineer (Gunner)

S/Sgt. Jesse H. Hudman was evidently not a regular member of the Thompson crew, and does not appear in the above photos. However, here’s an image of his memorial tombstone, at Dale Cemetery in Ossining, New York, followed by a news item from the Citizen-Register, of Ossining, N.Y., on May 22, 1946, regarding memorial services in his honor, which were held on Sunday, May 20, of that year.

Born 1918

Mrs. Florence L. Hudman (wife), 10 Marble Place, Ossining, N.Y.

Mrs. Carrie Hudman (mother), Gilbert Park, N.Y.

Memorial Tombstone – at Dale Cemetery, Ossining, N.Y. (photo by Jean Sutherland)

Notices about Sgt. Hudman appeared in the Citizen-Register, of Ossining, N.Y., on May 22 (above) and 25, 1946. His name also appeared in an honor roll of WW I, WW II, and Korean War military casualties from Ossining which was published in the Citizen-Register on February 21, 1952.

______________________________

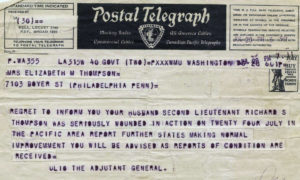

Due to the severity of his wounds, Rick would fly no more combat missions. He faced a very lengthy period of recovery.

This telegraph to his wife, at her family’s Boyer Street address in Philadelphia, dated July 28, informed Elizabeth Thompson of her husband’s injuries:

REGRET TO INFORM YOU YOUR HUSBAND SECOND LIEUTENANT RICHARD S THOMPSON WAS SERIOUSLY WOUNDED IN ACTION ON TWENTY FOUR JULY IN THE PACIFIC AREA REPORT FURTHER STATES MAKING NORMAL IMPROVEMENT YOU WILL BE ADVISED AS REPORTS OF CASUALTIES ARE RECEIVED

ULIO THE ADJUTANT GENERAL

______________________________

______________________________

Dick’s name appears (top right) in this casualty list published by the Philadelphia Inquirer on August 12, 1943, which represents only a part of the larger, nationwide casualty list released that day by the War Department.

Rich surmises that his father was well enough to travel back to the United States by October of 1943, based on a telegram – from Dick to Elizabeth – dated on the 18th of that month.

Some time around Christmas, 1943, while recovering at Brooke Army Hospital (now Brooke Army Medical Center) at Fort Sam Houston, Texas, Dick was featured in a broadcast on Armed Forces Radio.

In the photo below, the civilian holding the microphone is Dick Smith, the officer is Brooke Army Hospital Commander Brigadier General B.C. Beach, and the nurse is 1 Lt. Florence E. Judd, who made a full career as a military nurse, eventually rising to the rank of Major. According to George E. Omer’s 1957 article in Kansas History (“An Army Hospital: From Horses to Helicopters”), she, “…became the Fort Riley hospital chief nurse following an assignment at Walter Reed Army Hospital. Major Judd earned her R.N. degree in 1934 from Saint Mary’s Hospital in East Saint Louis and her postgraduate studies have earned a B.S. in nursing education from Columbia University and an M.S. in hospital administration from Baylor University.”

An excerpt of this interview follows this image of Dick, who appears to have an understandably pensive expression. Note especially the text…

“[Dick cut this part out: It’s a pretty sight, that flack, red and green fire bursting in the air around you.],” which presumably was never broadcast.

…and…

SMITH: That must have been a wonderful crew you had.

THOMPSON: They were swell. And I have been pretty upset about the latest news I’ve had about them. I got shipped home with this leg but they – they stayed in the fight. I’ve been told recently the plane is missing and that means all of the crew too.

Well, there are some events for which the fewer words, the better.

The transcript of the broadcast follows…

SMITH: Wherever our forces go, the Army Nurses Corps follows. Wherever the fighting is, they are near by – and these boys in this hospital can tell you it is a wonderful thing to have them. When a man is wounded, it is comforting indeed, to know they are present, to be in their capable, responsible hands. Many of the nurses here in Brooke General Hospital have seen duty overseas. For instance, here is First Lieutenant Florence E. Judd. She put in a year’s service in a base hospital in the Fiji Islands. It was a magnificent job you nurses did there, Lt. Judd. I spent some time in that hospital you were in – and I say thank you.

SMITH: Wherever our forces go, the Army Nurses Corps follows. Wherever the fighting is, they are near by – and these boys in this hospital can tell you it is a wonderful thing to have them. When a man is wounded, it is comforting indeed, to know they are present, to be in their capable, responsible hands. Many of the nurses here in Brooke General Hospital have seen duty overseas. For instance, here is First Lieutenant Florence E. Judd. She put in a year’s service in a base hospital in the Fiji Islands. It was a magnificent job you nurses did there, Lt. Judd. I spent some time in that hospital you were in – and I say thank you.

JUDD: You needn’t thank me or any other Nurse. I often think the hard work we did there, night and day, was its own reward. The lives we saved in those hospitals were worth all the work – and we felt that we were actually doing something in this fight for freedom everybody is always talking about.

SMITH: You had to work hard in those hospitals.

JUDD: Yes – everything was difficult because at that time we were starting from scratch. We were rushed there immediately after Pearl Harbor and had with us only such equipment as could be carried quickly. It was a rush job but I’m proud to say that it was also a good job. Some facilities were not comparable to those here at home, but we had the best equipment, best doctors, the best trained corpsmen – and it was amazing to see how rapidly the boys recovered from their injuries.

SMITH: You want to be sent overseas again?

JUDD: Definitely. Once you have seen the war at close hand, you feel strange in the ordinary, peaceful atmosphere of home again. You keep recalling all the suffering you have seen. You want to get back into it to see that you can do to lessen it. You feel guilty enjoying anything when you know how miserable, how dreadful are the things our men must face. Maybe what you do is very little, but at least, you are in it.

SMITH: Don’t you feel you are in it here, serving in this hospital which is receiving overseas casualties?

JUDD: Of course, I do. But this is home. Over there the men are far from home. It is a terrible thing to be wounded far from home.

SMITH: It must be.

JUDD: But we never heard the boys complain. They were the best patients I ever worked with. They were appreciative of even the- least attention.

THOMPSON: And they should have been. They had the best nurses in the world to give them attention.

JUDD: Thank you, sir.

THOMPSON: I’m Lieutenant Richard S. Thompson, Mr. Smith. I want to say a thing or two on this broadcast, if I may.

SMITH: Of course, you may.

THOMPSON: Just something I’ve had on my chest.

SMITH: Go ahead.

THOMPSON: I was in the Air Force, pilot of a bomber on patrols out of Hawaii.

SMITH: Is that where you were wounded?

THOMPSON: Oh, no. I got mine, flying in a nuisance raid over Wake Island.

SMITH: Tell us about that.

THOMPSON: Well, you know Wake is a pretty small island –

SMITH: But a famous one.

THOMPSON: That’s right. It cost the Japs plenty to take it from our Marines, and they have it well defended today. They mean to make it cost us when we take it back. We went over on our raid one day about noon. And we were very lucky. We caught twenty Japanese Zero planus on the ground. I’m pleased to report our aim was good and we put all of them out of commission. But we didn’t get away scot free – at least I didn’t.

SMITH: What happened?

THOMPSON: Well, there were thirty Zeros which weren’t on the ground – and they weren’t out of commission either. They settled on us like hornets. The flack was bad, too. [Dick cut this part out: It’s a pretty sight, that flack, red and green fire bursting in the air around you.] And it scares the devil out of you. It’s meant for you. Just a few more feet in your direction – and it is yours forever.

SMITH: Was it flack which wounded you?

THOMPSON: No – gun fire from one of the Zeros. Ripped right through my leg. I passed out: so I missed most of the excitement. The co-pilot later told me they downed nine of those thirty Zeros.

SMITH: That must have been a wonderful crew you had.

THOMPSON: They were swell. And I have been pretty upset about the latest news I’ve had about them. I got shipped home with this leg but they – they stayed in the fight. I’ve been told recently the plane is missing and that means all of the crew too.

SMITH: That’s not very good news.

THOMPSON: But that isn’t what I had on my mind to say. I’ve get a baby boy, three months old.at home, and I’ve never seen him.

SMITH: Surely you’ll get to see him soon.

THOMPSON: Yes, right away. But think of the thousands of other American men overseas who won’t get to see their children soon – even for a year or so, maybe never. Millions of men, average American fellows like the boys you have talked with tonight, are spending the best years of their life away from the people they love, away from the opportunities they had planned to take advantage of. We all know it’s got to be that way. And you don’t hear those men complaining, though I can tell you they get pretty burned up sometimes at the softness and blindness of certain people back home, people whom the war has never touched and who don’t know what it is like to fight an enemy who isn’t playing a game with you but means to kill you for keeps. Yeah, I’ve got an injured leg, but at that I came out light. Those boys who talked to you a little while ago didn’t tell you all the things they know about that jungle warfare going on – right this minute – in the South Pacific. They talked about foxholes. You know what those foxholes are like? They’re not nice, clean holes in the earth. They are holes that the jungle rains fill with water and mud – and yet those boys have to stay in them. Sometimes they fill up with blood and you are in that, too. Those filthy, muddy holes become a man’s home. And that jungle they talk about. It is as bad as an enemy; it’s no pretty green land of palms and flowers. It is a matted mass of vines and trees and at times the ground beneath your feet is not ground but mud up to your knees and up to your thighs. And worst of all it hides an enemy you can’t see – all around you, sniping at you from a tree top or hiding on the ground right under you. And that enemy – the boys didn’t tell you all they know about him either. They didn’t tell you about those wounded men the Japs had found and slashed to shreds before our medical corpsmen could get them back to the aid stations. I listen to the radio and read the newspapers and they talk about what a good investment War Bonds are and how if you buy them you’re keeping down inflation. Frankly, I don’t get it. Does the government have to beg you to buy War Bonds? If you had seen sore of the things we’ve seen, you’d jump at the chance to get ammunition and other supplies to the men overseas. What is all this begging you to buy War Bonds anyhow? I know a lot of people are buying plenty of War Bonds, but what’s wrong with the rest of you? I don’t get it.

SIIITH: We return you now to our downtown studio.

______________________________

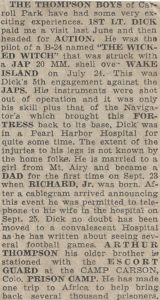

Here’s a wartime article from an un-named (probably Philadelphia-area) neighborhood newspaper, covering the experiences of Dick and his brother Arthur. Note that the story mentions Dick having piloted a “Fortress” (!) back to Funafuti, when the aircraft was actually (!) a B-24, and Lieutenant Lowry took control of the plane.

And, here are two photos of the Thompson family, at Brooke Army Hospital. Brother Art and his wife Kay stand at rear, while Dick, Betty, and baby son Richard, Jr. (born in September, 1943) in foreground.

And, here are two photos of the Thompson family, at Brooke Army Hospital. Brother Art and his wife Kay stand at rear, while Dick, Betty, and baby son Richard, Jr. (born in September, 1943) in foreground.

Unfortunately, Dick’s leg would never completely heal. It was amputated in 1946, with Dick being medically retired from the military.

______________________________

Life moves forward.

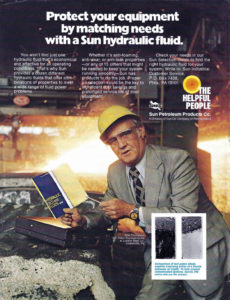

Here’s a picture of Dick in a 1974 advertisement for the Sun Petroleum Company. However, there’s no actual recollection of how he came to work for Sun. As remembered by Rich, his grandfather [Dick’s father], “…Everett sold Cabot paints so being around a salesman must have turned him into one. His brother Art had a paint store in Long Beach, CA so that sort of thing was in their DNA. … It’s easy for me to say he was very good at it as he was chosen to appear in trade magazines representing Sunoco. …He enjoyed working for Sun for at least most of his career. I seem to remember however, that towards the end of his career, it was like they were trying to push out the good old boys and their way of doing business over 3 martini lunches – but that’s just my take. I think he was about ready for more golf, flying to Myrtle Beach for more golf, visiting his brother in CA and doing things not possible while raising a family.”

This image, from the late 1970s, was taken at Pearson Airport, Vancouver, Washington. Rich, “lived on the hill behind the airport in late ‘70s and dad really liked being able to sit in the house or porch and look across the field at “Joliet” (“four niner J”) while he was having a martini.”

This image, from the late 1970s, was taken at Pearson Airport, Vancouver, Washington. Rich, “lived on the hill behind the airport in late ‘70s and dad really liked being able to sit in the house or porch and look across the field at “Joliet” (“four niner J”) while he was having a martini.”

Though the Second World War changed Dick’s life, it did not dominate it. For example, though letters were naturally exchanged with his family after his wound in 1943, he did not keep a diary. According to Dick, “He didn’t have any really bad / negative things to say about his situation or the enemy (e.g. I have one letter where his mother makes mention of “those dirty japs”!)”

Though the Second World War changed Dick’s life, it did not dominate it. For example, though letters were naturally exchanged with his family after his wound in 1943, he did not keep a diary. According to Dick, “He didn’t have any really bad / negative things to say about his situation or the enemy (e.g. I have one letter where his mother makes mention of “those dirty japs”!)”

Similarly, Dick’s discussions of and attitude about the war remained “light”. Rich remembers, “…photos of him shortly after the amputation of him showing off his “stump” at family gatherings and waving it like his arm at folks that were there.

“While growing up, I remember waking up one night when the folks had an adult poker party going and his prostheses was in the center of the table to cover a bet.

“I took him to a party here in Oregon while he was visiting where there was a pool in the back yard. One of the smart-asses among the guests … took the liberty of pushing him into the pool – fully dressed. He could swim like a fish and came back over to the edge of the pool where the ‘perp’ was standing, took off his leg and threw it up in the deck and said – ‘Now look what you’ve done!’ One of the few times I’ve ever known that guest to be speechless.

But, he did seem to have been particularly close to co-pilot, John Lowry, in whose memory he was proud to have named his second son, John. In time, John Thompson attended college in Atlanta, and became friends (“…he was given V.I.P. treatment…”) with Lowry’s wife Margaret, who had remarried and had twin daughters and lived in Smyrna.

As remembered by John, “There were two family ‘reunions’ with Margaret Lowry / Mellon. The first was in 1966 when Mom came down to pick me up after my first year at college. There was a relationship between the two wives which indicates that they were together during some part (training)? of Dad and Jack’s early military career. The second and last reunion … was in 1969 when my parents … drove down for my graduation.”

______________________________

The past remains within the present. In June of 2015, this took the form of a visit by the Collings Foundation Wings of Freedom Tour to Portland, Oregon. Rich, “…got there Sunday afternoon and didn’t even get to see the planes in the air but vowed to return at next opportunity and participate in what they call a “flight experience” and actually take a ride in the B-24 WITCHCRAFT.

“During the visit, the flight engineer found me and three other people up on the flight deck. He wanted us out of there and apologized that they forget to put the ‘NO ENTRY’ rope across the opening. While talking with one of the people – an elderly gentleman accompanied by his family – the engineer learned that this fellow flew B-24s during WW II training pilots, and became very cordial, telling the old pilot, have a seat, stay as long as he liked, and insisted he leave a note and sign his log book.

Then I saw my chance and dug out an old photo of dad with his head out the pilot’s window on the WICKED WITCH. He asked “Who is this”? I said, “My Father”. His jaw dropped to the floor! Once recomposed, he squatted down and looked down the bomb bay catwalk, now crowded with people and told them he had a pilot and the son of another pilot on the flight deck and asked for their patience while we finished up.

I met the engineer later and showed him the photos you’ve been looking at and gave him a big THANK YOU.

Great day!”

The memory of that 2015 day – full circle from July of 1943 – is shown below.

______________________________

______________________________

Looking back, Rich’s father, “…was always quick to relate how lucky he was to have only lost his leg and that the whole crew went out on the next mission and ended up missing in action.”

And that brings us to a story that, whether true or apocryphal, is deep with meaning, carrying a message universal and perhaps eternal. Curiously, it is a very old Chinese Taoist story about a simple farmer in a poor country village.

While such a tale nature appears – on first reading – to be completely unrelated to aviation and military history, on contemplation, it actually encompasses both, and much more.

For, it is a tale about the nature of life.

______________________________

He [the farmer] was considered very well-to-do, because he owned a horse which he used for plowing and for transportation.

One day his horse ran away.

All the neighbors exclaimed how terrible this was, but the farmer simply said,

“Maybe.”

A few days later the horse returned and brought two wild horses with it.

The neighbors all rejoiced at his good fortune, but the farmer just said,

“Maybe.”

The next day the farmer’s son tried to ride one of the wild horses; the horse threw him and broke his leg.

The neighbors all offered their sympathy for his misfortune, but the farmer again said,

“Maybe.”

The next week conscription officers came to the village to take young men for the army.

They rejected the farmer’s son because of his broken leg.

When the neighbors told him how lucky he was, the farmer replied,

“Maybe.”

(Maybe.)

– February, 2019

Acknowledgements

I’d like to extend my deep appreciation to Rich Thompson and his brother and sister, for sharing the photographs, documents, and information that have made this blog post possible.

References and Suggested Readings

Bell, Dana, Air Force Colors – Pacific and Home Front, 1942-47, Squadron / Signal Publications, Carrollton, Tx., 1997

Birdsall, Steve, B-24 Liberator in Action – Aircraft Number 21, Squadron / Signal Publications Inc., Warren, Mi., 1975

Blue, Allan G., The B-24 Liberator – A Pictorial History, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, N.Y., 1975

Cleveland, W.M., Grey Geese Calling : Pacific Air War History of the 11th Bombardment Group (H), 1940-1945, Portsmouth, N.H., 1992

Davis, Larry, B-24 Liberator in Action – Aircraft Number 80, Squadron / Signal Publications Inc., Carrollton, Tx., 1987

Forman, Wallace R., B-24 Nose Art Name Directory – Includes Group, Squadron and Aircraft Serial Numbers and Photo Availability, Specialty Press, North Branch, Mn., 1996

Howard, Clive and Whitley, Joe, One Damned Island After Another, The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, N.C., 1946

Livingstone, Bob, Under the Southern Cross: The B-24 Liberator in the South Pacific, Turner Publishing Company, Paducah, Ky., 1998

Rust, Kenn C., Seventh Air Force Story, Historical Aviation Album, Temple City, Ca., 1979

Rust, Kenn C. and Bell, Dana, Thirteenth Air Force Story, Historical Aviation Album, Temple City, Ca., 1981 (The Grey Geese were assigned to the 13th AF from January through May of 1943. Subsequently, they were part of the 7th AF.)