Deprecated: Function create_function() is deprecated in /home3/emc2ftl3/public_html/wp-content/plugins/wp-spamshield/wp-spamshield.php on line 2033

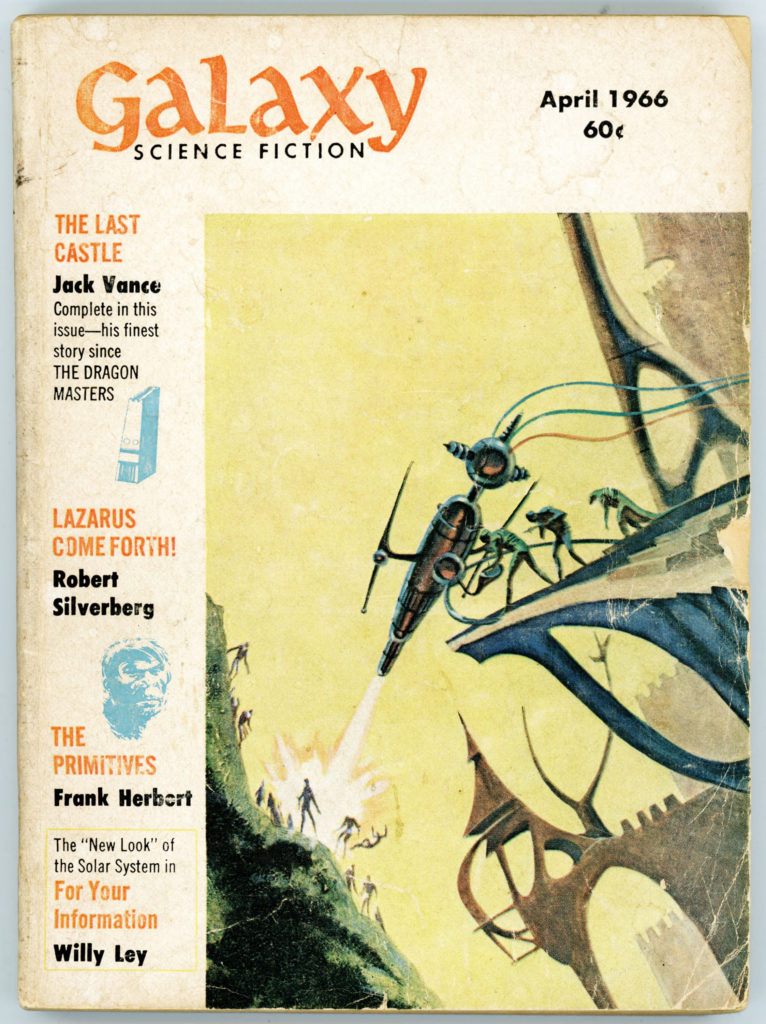

Over five decades ago, multiple Hugo and Nebula Award winner Frederick Pohl wrote an editorial entitled “Where the Jobs Go”, which appeared in the April, 1966 edition of of Galaxy Science Fiction. The impetus for his essay was the New York City Transit Strike of January, 1966 (1). That event created an intellectual springboard for musings about the relationship between automation, information technology and employment, particularly in terms of the diminution – if not outright elimination – of existing occupations. Writing in the midst of the strike – with the cancellation of bus and subway transportation affecting millions of New Yorkers – the issues Pohl raised are even more pressing today than in 1966.

Pohl presented a specific example of the effects of technological change on employment, through his discussion about the future of publishing, with representatives of the Philadelphia-based Institute for Scientific Information (a.k.a. “ISI”) (2), and, Simon and Schuster. He clearly foresaw what today would be termed “on demand” publishing. Though he didn’t specifically estimate when this would occur, he understood that for the replication of printed information, the central dependence on and necessity for human activity, and in turn specific job categories, could in time be eliminated. In the mid-1960s, this was in the areas of linotype operation, printing, binding, storage, and sales. Bypassing and eventually supplanting the these steps – and the human role in them – could enable a customer; a user; a consumer; to produce a book, “on order, anywhere in the world”.

Pohl presented a specific example of the effects of technological change on employment, through his discussion about the future of publishing, with representatives of the Philadelphia-based Institute for Scientific Information (a.k.a. “ISI”) (2), and, Simon and Schuster. He clearly foresaw what today would be termed “on demand” publishing. Though he didn’t specifically estimate when this would occur, he understood that for the replication of printed information, the central dependence on and necessity for human activity, and in turn specific job categories, could in time be eliminated. In the mid-1960s, this was in the areas of linotype operation, printing, binding, storage, and sales. Bypassing and eventually supplanting the these steps – and the human role in them – could enable a customer; a user; a consumer; to produce a book, “on order, anywhere in the world”.

Which is where we’re at today.

Another notable aspect of Pohl’s editorial was the realization that there is a natural and perhaps inevitable tendency to perceive the uses, effects, and implications of any new technology through the context of the past. Pohl’s “twelfth-century armaments expert” has appeared throughout history in all venues of human endeavor: technological, military, economic, educational, and political.

Pohl’s other examples included bank tellers, retail clerks, and accounts. he realized that the commonality among these occupations was their general predictability and codification. His prediction: Technological advances in electronics (“black boxes”) would eventually supplant established work activities, let alone categories of employment.

Pohl didn’t really address issues that would in time (our time) be wrought by these changes. Instead, he concluded by simply suggesting – simplistically and optimistically; resignedly and pragmatically – their acceptance: “Postponing this revolution or slowing it down isn’t going to make us very well indeed; let’s swallow it and get it over!”

Perhaps he couldn’t have foreseen – could anyone? – the magnitude to which the issues he discussed – in terms of both physical and intellectual activity; in terms of social cohesion; in terms of geopolitical stability; in terms of ethics and morality – would rise to prominence only a few decades later.

His editorial follows below…

____________________

WHERE THE JOBS GO

As this is written, the city of New York is tying itself in knots because of a strike in the Transport Workers Union. All of the city subways, and nearly all of its buses, are idle. Workers can’t get to their jobs; shoppers can’t get to stores; salesmen can’t call on their customers; theatergoers can’t reach the plays for which they have bought tickets months in advance – in a word, the normal operations of the city have stopped.

All of this costs money. The current guess is that the paralysis of the city is costing it something like $100,000,000 a day or substantially more than the combined expense of the space program, the war in Vietnam and Medicare put together.

It is our opinion that this is only a beginning, because it begins to look clear to us that the real squeeze brought about by automation is going to express itself – has already begun to express itself – in a wave of strikes such as we’ve never seen before.

True, automation is not technically an issue in this strike. The TWU had its confrontation with the machines – the “Headless Horseman”, as Mike Quill called it – when the subways installed the first automated tracks a few years ago. At union insistence the Transit Authority provided a standby motorman on the train, whose principal efforts consisted of walking from one end of the train to the other each time it came to the end of its run. The automated was destroyed accidentally in a fire after a year’s trial – apparently to the unspoken relief of all parties. There has been no announcement of any plan to build another, but we would judge that its ghost haunts the negotiating tables.

Nearly all of the subway jobs involved are relatively unskilled – changemakers, conductors, station guards, motormen – with only a comparatively small number involved in maintenance, repair, construction and other more technically demanding jobs. And this is the edge that cuts. The subway workers have not been through the automation shakeout, when a large number of repetitive jobs are obsoleted and the jobs that are left require more training and more skill.

In other words, their productive capacity has not yet been multiplied by the machine factor. This produces two opposed points of view, both of them unarguable. Say the subway administrators and the public at large: These jobs just don’t call for that kind of money, and besides it would make the expense of running the subways ridiculously high. Say the subway workers: Other people putting in the same hours earn much more; we have to live in the same world with them, we have to compete with them to buy what we want in the stores, and we can’t do it unless we make as much money as they do.

This is the classical formula for the hardest-fought wars: both sides are right.

Is there any way to avoid more and even worse strikes than this one in the transition to the Cybernetic Age?

We doubt it very much. Certainly what is happening now is not the final struggle; in fact, the issues haven’t even been joined. The present subway strike is only a taste of what will come when “Headless Horsemen” are beginning to come out of the shops for all the major routes – and that day cannot be far off. Remember the newspaper strike of a couple years ago. That one was indeed fought on the issue of automation; but we have it on the word of the man who designed the systems that triggered the strike, Eugene Leonard, that it was the wrong fight at the wrong time over the wrong issues – because the systems that caused the strike were already obsolete at the time.

Not long ago we took part in a radio program with the aforementioned Gene Leonard, along with Arthur Elias of the Institute for Scientific Information and Henry Simon of Simon & Schuster, talking about the future of the publishing business in the Cybernetic Age. We started by discussing automated typesetting, and it took exactly twelve minutes by the studio clock before we had reached a proposal for high-speed facsimile machines which would produce a book to your order, anywhere in the world. In twelve minutes we not only got rid of the human linotype operator, but abolished the linotype itself and went on to obsolete the printing press, the binderies, the warehouses and the publishing house’s road salesmen.

Is such a new kind of publishing technologically feasible right now? Certainly. Is it likely to come into being in the next few years? Certainly – cultural lag doesn’t permit us to move that fast – but it, or something like it, is surely the shape of the publishing business some time in the future.

We tend to think of automation’s effect on our own jobs in terms of a wilier, cheaper competitor to do the same things we’re doing right now. In the event it isn’t going to be like that at all. An analogy: Suppose we resurrected some twelfth-century armaments expert and asked him how he thought we should employ the resources of modern technology to build weapons. No doubt he would be delighted; at once he would proceed to the fabrication of sharper lances, springier bows, truer shafts; and just how far would his troops get against H-bombs or napalm grenades?

Unfortunately, our own outlook on our own jobs is largely medieval. The long lines of girls who used to assemble radio components don’t get replaced by speedier machine assemblies; they get put out of business entirely by printed circuits. The stockbreeders who used to export power to the cities in the form of draft animals weren’t hurt by competition from more efficient breeders. They simply ceased to have a market when the cities began exporting power to the farms, in the form of tractors and trucks.

Just so, in the long run (which may be measured in years or even months, these days), the bank tellers and retail clerks and accounting departments are not as likely to be replaced by whirring black boxes which accept ten-dollars bills and return change as they are to be retired completely by new electronic credit systems. The machines don’t confine themselves to doing our jobs faster and more reliably – and cheaper. They make it unnecessary for a great many of our jobs to be done at all.

Meanwhile, we have the strikes. More and more of them, we would bet; worse and worse strikes, costing us more and more money. (Each day’s loss to New York under the current subway strike would build a couple dozen handsome new schools.)

As long as Smith, operating at a job with only his own decision-making power, lives next door to Jones, whose decision-making power and consequent productivity is multiplied by the machine factor, they’ll go on; because Smith eats as many pork chops in a year as Jones, his children wear out as many clothes, his car uses as much gas – and he wants as much money. Postponing this revolution or slowing it down isn’t going to make us very well indeed; let’s swallow it and get it over! – THE EDITOR

___________________

Akin to my prior post “The Past As Prologue: Technology, Work, and The Future – The View From 1947” (which was based on a New Republic article “Communications Revolution” from 1947) “this” post includes – below – links to a variety of articles, essays, and a video or two. They cover topics such as the effect of the Internet and technological change upon employment, and, social stability (both domestically and internationally); the return – with a searing vengeance – of the question of “class” in contemporary America (it never really went away), whereby social status has become a zero-sum-game conferred through thought, belief, pose, and moral intent; the impact of automation and robotics on employment; the economic and social corrosiveness of an informational oligopoly; the cognitive and cultural effects of “social” media. And, in an age of ostensible meritocracy, the not uncommon lacuna between intelligence and wisdom.

The commonality among these writings is that most (not all) have been published since February of this year (2017), when I created that “first” post covering the 1947 essay from The New Republic.

For future blog posts concerning technology, economics, employment, and society, I hope to present links to similar writings, as they become available.

____________________

Thoughts of Note

Uncertainty Without Principles

Rod Dreher – Economic Insecurity

(The American Conservative – February 20, 2017)

Nicholas N. Eberstadt – Our Miserable 21st Century

(Commentary – February 15, 2017)

Esther Kaplan (Photography by David M. Barreda) – Losing Sparta: The Bitter Truth Behind the Gospel of Productivity

(Virginia Quarterly Review – Summer, 2014)

Michael Lind – The New Class War

(American Affairs – Summer, 2017)

David Ramli – Jack Ma Sees Decades of Pain as Internet Upends Older Economy

(Bloomberg.com – April 23, 2017)

Walter Scheidel – The Only Thing, Historically, That’s Curbed Inequality: Catastrophe

(The Atlantic – February 21, 2017)

Yves Smith – How Financialization and the “New Economy” Hurt Science and Engineering Grads

(Naked Capitalism.com – May 12, 2017)

____________________

The New Zero Sum Game: Social Status in America* in the 21st Century (The Aristocracy Reborn?)

Matt Stoller – On Mocking Dying Working Class White People

(Medium.com – March 24, 2017)

Twitter: https://twitter.com/matthewstoller

Lambert Strether – Frank Rich, the Trump Voter, and Liberal Eliminationist Rhetoric

(Naked Capitalism.com – March 27, 2017)

*And beyond.

____________________

Avarice In the Guise of Altruism

Kevin D. Williamson – Why Corporate Leaders Became Progressive Activists

(National Review – March 13, 2017)

Michael Hobbes – Saving the World, One Meaningless Buzzword at a Time

(Foreign Policy – February 21, 2017)

____________________

Robotics and Jobs: The Unknown Future

Nicholas Carr – The Digital Industrial Complex

(Rough Type – May 12, 2017)

Nicholas Carr – The Robot Paradox

(Rough Type – May 16, 2017)

Tyler Cowen – Industrial Revolution Comparisons Aren’t Comforting

(Bloomberg.com – February 16, 2017)

Jack Ma – World Leaders Must Make ‘Hard Choices’ or the Next 30 Years Will be Painful (CNBC.com – June 21, 2017)

Cade Metz – The AI Threat Isn’t Skynet, It’s the End of the Middle Class

(Wired – February 20, 2017)

Claire C. Miller – The Long Term Jobs Killer is not China. It’s Automation

(The New York Times – December 21, 2016)

Claire C. Miller – Why Are We Doing This to Ourselves

(The New York Times – December 28, 2016)

Claire C. Miller – How to Prepare for an Automated Future

(The New York Times – May 3, 2017)

Rick Moran – The Huge Economic Issue That Washington Isn’t Talking About

(Pajamas Media – February 12, 2017)

Clive Thompson – The Next Big Blue-Collar Job Is Coding

(Wired – February 8, 2017)

Victoria Turk – Don’t Fear the Robots Taking Your Job, Fear the Monopolies Behind Them

(Motherboard.com – June 19, 2014)

Marcus Wohlsen – When Robots Take All the Work, What’ll Be Left for Us to Do?

(Wired – August 8, 2014)

____________________

From Prose to Power. And, More Power.

Franklin Foer – Amazon Must Be Stopped: It’s too big. It’s cannibalizing the economy. It’s time for a radical plan.

(The New Republic – October 9, 2014

George Packer – Cheap Words: Amazon is Good for Customers. But Is It Good for Books?

(The New Yorker – February 17 and 24, 2014)

Matt Stoller – Why We Need to Break Up Amazon… And How to Do It

(Medium.com – October 16, 2014)

Twitter: https://twitter.com/matthewstoller

____________________

“Social” Media

Nicholas Carr – Zuckerberg’s World

(Rough Type – February 28, 2017)

Nicholas Carr – How Technology Created A Global Village and Put Us at Each Other’s Throats

(The Boston Globe – April 21, 2017)

David Foster – Mark Zuckerberg as Political and Social Philosopher

(ChicagoBoyz.net – March 7, 2017)

Annalee Newitz – Mark Zuckerberg’s Manifesto is a Political Trainwreck

(Arstechnica.com – February 18, 2017)

____________________

Intelligence Or Wisdom

Andy Beckett – Accelerationism – How a Fringe Philosophy Predicted the Future We Live In

(The Guardian – June 5, 2017)

Gregory Ferenstein – The Disrupters: Silicon Valley elites’ vision of the future

(City Journal – Winter, 2017)

E.M. Oblomov – Intelligentsia Elegy: American Intellectuals are at Odds with the Workings of Democracy

(City Journal – February 3, 2017)

Paul G. Raven – We’re Reading Up on Transhumanism

(Arcfinity.com – 2014)

Andrew Russell and Lee Vinsel – Hail the Maintainers: Capitalism Excels at Innovation But is Failing at Maintenance, and For Most Lives It Is Maintenance That Matters More

(Aeon.com – April 7, 2016)

____________________

On a hopefully lighter (!) note, this post ends with two illustrations that graced the interior of the April 1966 issue of Galaxy, both of which complemented Jack Vance’s remarkable Hugo and Nebula Award winning novella, “The Last Castle”. They’re by science-fiction artist Jack Gaughan. They show a Phane and a Mek.

To learn more, you can read about “The Last Castle” at Battered, Tattered, Yellowed, & Creased.

(For more literary illustrations, particularly from the “Golden Age” of science-fiction, you might want to visit: http://wordsenvisioned.com/.) [Shameless plug.]

Notes

(1) From Wikipedia: New York City’s Transport Workers Union, and, Amalgamated Transit Union, called a strike against the city’s Transit Authority on January 1. The strike was resolved by the 13th, through a package comprising, “wages increases from $3.18 to $4.14 an hour, an additional paid holiday, increased pension benefits, and other gains.” The strike also resulted in the passage of the Taylor Law, which defined, “rights and limitations of unions for public employees in New York.”

(2) Also known as “ISI”; later “Thomson-ISI”, then the Intellectual Property & Science business of Thomson Reuters; now “Clarivate Analytics”. The title of the enterprise’s next iteration – should one occur – is unknown.

References

New York City 1966 Transit Strike, at

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1966_New_York_City_transit_strike

Frederick Pohl (biography), at:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederik_Pohl

“The Last Castle” (by Jack Vance), at:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Last_Castle_(novella)

____________________

____________________

PHANE

MEK