The preeminent science-fiction magazine of the mid-twentieth century was Astounding Science Fiction, which rose to prominence under the editorial reign of John W. Campbell, Jr. First published in January 1930 as Astounding Stories of Super Science, the magazine has continued publication under the leadership of several editors and through various title changes, now being known as Analog Science Fiction and Fact.

Though by definition and nature a science fiction publication, Astounding (akin to its post-WW II counterparts and rivals Galaxy Science Fiction, and, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (“F&SF”)) also published non-fiction material. Such non-fiction material included leading editorials, book reviews, and letters, as well as articles – typically, one per issue – about some aspect of the sciences. As in any serial publication, the nature of this content reflected the opinions and interests of the magazine’s readers, and, the intellectual and cultural tenor of the times.

A perusal of science articles in Astounding from the late 1940s reveals a focus on aerodynamics, astronomy, atomic energy, chemistry (organic and inorganic), computation, cybernetics, data storage, electronics, meteorology, physics, and rocketry. (Biology it seems, not so much!) Viewed as a whole, these subject areas – in the realm of the “hard sciences” – reflect interests in space travel (but of course!), the frontiers of physics, information technology, and the creation and use of new energy sources.

Let’s take a closer look.

Here are the (non-fiction) science articles that were published in Astounding Science Fiction in 1949:

January: “Modern Calculators” (Digital and analog calculation), by E.L. Locke; pp. 87-106

February: “The Little Blue Cells” (The “Selectron” data storage tube), by J.J. Coupling; pp. 85-99

March: “The Case of the Missing Octane” (Chemistry of petroleum and gasoline), by Arthur Dugan; pp. 102-113 (Great caricatures by Edward Cartier!)

April: “9 F 19” (Hydrocarbons), by Arthur C. Parlett; pp. 46-162

May: “Electrical Mathematicians” (Machine (electronic) calculation), by Lorne MacLaughlan; pp. 93-108

______________________________

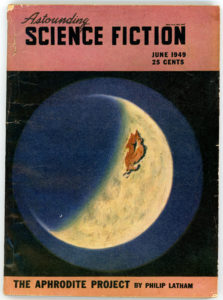

June: “The Aphrodite Project” (Determining the mass of the planet Venus), by Philip Latham; pp. 73-84. (Intriguing cover art by Chesley Bonestell.)

______________________________

______________________________

July: “Talking on Pulses” (Electronic transmission of human speech and other forms of communication), by C. Rudmore; pp. 105-116.

August: “Coded Speech” (Electronic speech; noise reduction), by C. Rudmore; pp. 134-145

September: “Cybernetics” (Review of Norbert Wiener’s book by the same title), by E.L. Locke; pp. 78-87

October – First article: “Chance Remarks” (Communication research), by J.J. Coupling; pp. 104-111

October – Second article: “The Great Floods” (Review of great floods in human history), by L. Sprague de Camp; pp. 112-120

November: “The Time of Your Life” (Time; Determining the length of the earth’s day), by R.S. Richardson; pp. 110-121

December – First article: “Bacterial Time Bomb“, by Arthur Dugan; pp. 93-95

December – Second article: “Science and Pravda“, by Willy Ley; pp. 96-111

Regardless of the topic, a notable aspect of the non-fiction science content of Astounding (likewise for Galaxy and F&SF) is that mathematics – in terms of equations and formulae, let alone Cartesian graphs – was kept to a minimum, if not eschewed altogether. Science articles largely relied upon text to communicate subject material, and often included photographs (especially for issues published during the latter part of the Second World War) and diagrams as supplementary material.

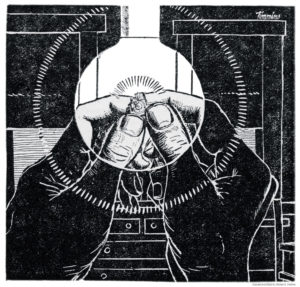

One such example – from February of 1949 – is presented below, in the form of J.J. Coupling’s article “The Little Blue Cells”.

______________________________

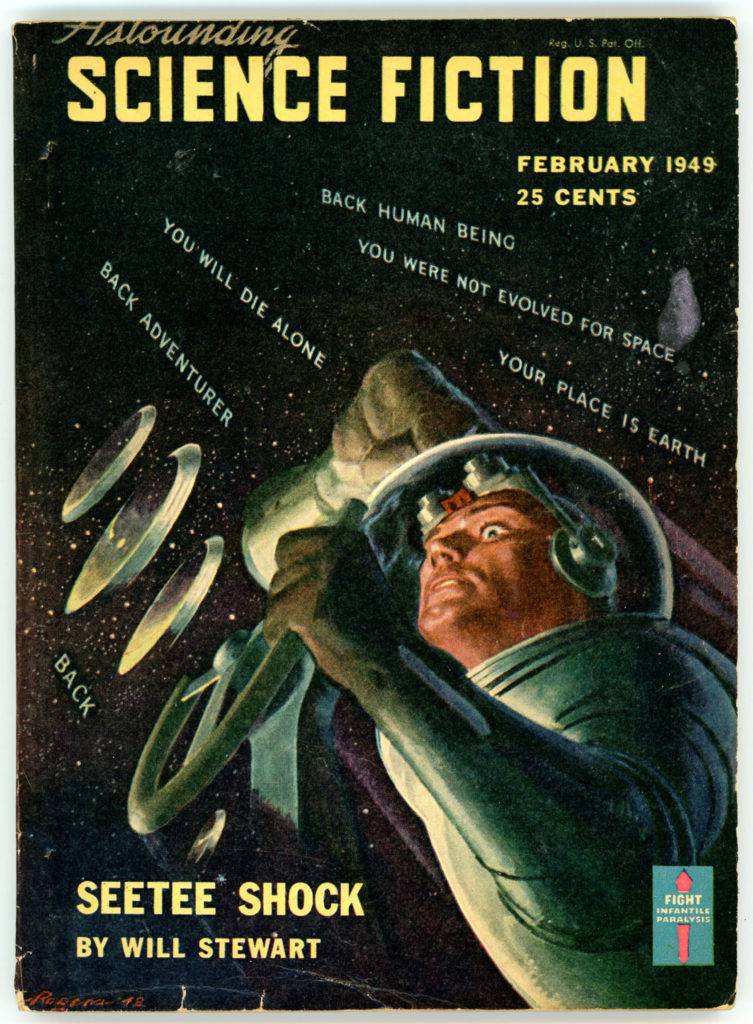

This issue features great cover art by Hubert Rogers for Jack Williamson’s (writing under the pen-name “Will Stewart”) serial “Seetee Shock”. The cover symbolizes adventure and defiance in the face of danger, by incorporating a backdrop of warning and admonition (“YOU WERE NOT EVOLVED FOR SPACE”; “BACK ADVENTURER”, and more) around the figure of a space-suited explorer, while cleverly using extremes of light and dark and a sprinkling of stars to connote “outer space”. Like much of Rogers’ best work, symbolism is as important as representation. (You can enjoy more of Rogers’ work at my brother blog, WordsEnvisioned.)

______________________________

______________________________

Coupling’s article is notable because it addresses a subject frequently addressed by Astounding, with continuing and likely indefinite relevance: recording, storing, preserving, and accessing information – computer memory.

The article focuses on Dr. Jan A. Rajchman’s – then – newly developed “Selectron Tube”, which was developed in the late 1940s at RCA (Radio Corporation of America) and about which extensive and rich literature is readily available, particularly at Charles S. Osborne’s wesbite. As implied and admitted by Coupling’s article, even at the time of the device’s invention there was ambivalence about its long-term economic and technical viability, despite its functionality and innovative design.

An image of a Selectron Tube, from Giorgio Basile’s Lamps & Tubes, is shown below. (Scroll down to end of post for a photograph showing a Selectron Tube in the hands of its inventor, illustrating its relative size.)

Eventually, the initial, 4,096-bit storage capacity Selectron Tube proved to be more difficult to manufacture than anticipated, and the concept was re-designed for a 256-bit storage capacity Tube. To no avail. Both tube designs were superseded by magnetic core memory in the early 1950s.

As for J.J. Coupling? Well…(!)…this was actually the nom de plume of Dr. John R. Pierce, a CalTech educated engineer, who had a long and rich literary career, writing for Astounding, Analog, and other publications. His lengthy oeuvre is listed at The Internet Speculative Fiction Database.

Today, Dr. Pierce’s “The Little Blue Cells” opens a window onto the world of information technology and scientific literature – for the general public – from over six decades gone by. His article, with accompanying illustrations, is presented below.

______________________________

THE LITTLE BLUE CELLS

By J.J. COUPLING

The most acute problem in the design of a robot, a thinking machine, or any of the self-serving devices of science-fiction is memory. We can make the robot’s body, its sensory equipment, its muscles and limbs. But thinking requires association of remembered data; memory is the essential key. So we present the Little Blue Cells!

Most of the robots I have met have been either man-sized androids with positronic brains to match, or huge block-square piles of assorted electrical junk. The small, self-portable models I admire from a distance, but I feel no temptation to speculate about their inner secrets. The workings of the big thinking machines have intrigued me, however. It used to be that I didn’t know whether to believe in them or not. Now, the Bell Laboratories relay computer, the various IBM machines and the Eniac are actually grinding through computations in a manner at once superhuman and subhuman. With the other readers of Astounding I’ve had a sort of inducted tour through the brain cases of these monsters in “Modern Computing Devices” by E.L. Locke. I’m pretty much convinced. It’s beginning to look as if we’ll know the first robot well long before he’s born.

Perhaps some readers of science fiction can look back to the old, unenlightened days and remember a prophetic story called, I believe, “The Thinking Machine.” The inventor of that epoch had first to devise an “electronic language” before he could build his electrical cogitator. The modern thinking machine of the digital computer type comes equipped with a special electronic alphabet and vocabulary if not with a complete language. The alphabet has the characters off and on, or 0 and 1, the digits of the binary system of enumeration, and words must certainly be of the form 1001-110—and so on. We may take it from Mr. Locke that somewhere in the works of our thinking machine information will be transformed into such a series of binary digits, whether it be fed in on paper tape or picked up by an electronic eye or ear. The machine’s most abstruse thought, or its fondest recollection – if such machines eventually come to have emotions – will be stored away as off’s and on’s in the multitudinous blue cells of the device’s memory.

I’m sure that I’m right in describing the memory cells of the machine as multitudinous and little – that is, if it’s a machine of any capabilities at all. To describe them as blue is perhaps guessing against considerable odds, but there are reasons even for this seemingly unlikely prognostication.

The multitudinous part is, I think, obvious. The more memory cells the machine has, the more the machine can store away – learn – the more tables and material it can have on hand, and the more complicated routines it can remember and follow. The human brain, for instance, has around ten billion nerve cells. It may be that each of these can do more than store a single binary digit – a single off or on, or 0 or 1. Even if each nerve cell stored only one digit, that would still make the brain a lot bigger than any computing machine contemplated at present. Present plans for machines actually to be built call for one hundred thousand or so binary digits, or, for only a hundred-thousandth as many storage cells as the brain has nerve cells. Mathematicians like to talk about machines to store one to ten million binary digits, which would still fall short of the least estimated size of the brain by a factor of one thousand to ten thousand. But, if one hundred thousand and ten million both small numbers as far as the human brain is concerned, they’re big numbers when it comes to building a machine, as we can readily see. It is because of the size of such numbers that we know that the memory cells of our thinking machine will have to be small, and, we might add, cheap.

For instance, some present-day computers use relays as memory cells. Now, a good and reliable relay, one good enough to avoid frequent failure even when many thousands of relays are used, costs perhaps two dollars. If we wanted a million cells, the cost of the relays would thus be two million dollars, and this is an unpleasant thought to start with. Further, one would probably mount about a thousand relays on one relay rack, and so there would be a thousand relay racks. These could perhaps be packed into a space of about six thousand square feet – around eighty by eighty feet. Then, there would have to be quite a lot of associated equipment, for more relays would be needed to make a connection to a given memory cell and to utilize the information in it. This would increase the cost and the space occupied a good deal. The thing isn’t physically possible, but it seems an unpromising start if we wish to advance further toward the at least ten sand-fold greater complexity of the human brain.

Fortunately, at just the time it as needed, something better than the relay has come along. That something, the possessor of the little blue cells, is the selectron. It is a vacuum tube which can serve in the place of several thousand relays. It promises to be reliable, small and, dually, at least, cheaper than relays, and in addition it is very much faster – perhaps a thousand-fold. The selectron was invented by an engineer, Dr. Jan A. Rajchman – pronounced Rikeman – for the purpose of making an improved computer and so its appearance at the right time is, after all, no accident. Instead, it is a tribute to Dr. Rajchman’s great inventive ability. Lots of people who worked on computers knew what the problem was, but only he thought of the selectron.

You might wonder how to go about inventing just what is needed, and if Dr. Rajchman’s career can cast any light on this, it’s certainly worth looking into. Did he, for instance, think about computers from his earliest technical infancy? The answer is that he certainly didn’t. I have a copy of his doctoral thesis, “Le Courant Résiduel dans Les Multiplicateurs D’Electrons Electrostatiques,” which tells me that he was born in London in 1911, that he took his degree at Le Ecole Polytechnique Federale, at Zurich and thereafter did research on a radically new type of electrically focused photo-multiplier – see “Universes to Order,” in Astounding for February, 1944. I am not sure how many different problems he has worked on since, but during the war he did do some very high-powered theoretical work on the betatron, as well as some experimental work on the same device. It would seem that the best preparation for inventing is just to become thoroughly competent in things allied to the field in which something new is needed.

What was needed in connects with computers was, as we have said, a memory cell, or, rather, lot, of them. What do these cells have to do? First of all, one must be able to locate a given cell in the memory so as to put information into it or take information out. Then, one must be able to put into the cell the equivalent of a 0 or a 1. One must have this stay there indefinitely, until it is deliberately changed. Finally, one must be able to read off what is stored in the cell; one must be able to tell whether it signifies 0 or 1 without altering what is in the cell. The selectron has these features.

You might be interested in some of the earlier suggestions for using an electron tube as a memory in a computing machine. The electron beam of a cathode ray tube sounds like just the thing for locating a piece of information, for instance. One has merely to deflect it the right amount horizontally and vertically to reach a given spot on the screen of the tube. One wishes, however, to store a particular piece of information in a particular place and then to find that same place again and retrieve that same piece of information. This would mean producing the exact voltages on the deflecting plates when the formation was stored, and that is by no means easy. Further, if the accelerating voltage applied to the tube changes, the deflecting voltage needed to deflect the beam to a given place changes, and this adds difficulty. When we realize further that our memory simply must not make mistakes, we see that there are real objections -to locating and relocating a given spot by simply deflecting an electron beam to it. The selectron has a radically different means for getting electrons to a selected spot – the selectron grid.

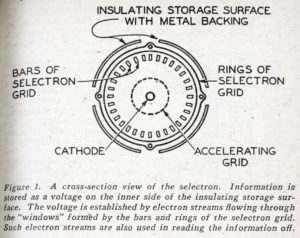

The features of the selectron which Dr. Rajchman holds in his hand – page 163 – are illustrated simply in Figure 1. There is a central cathode and around it a concentric accelerating grid. When this grid is made positive with respect to the cathode, a stream of electrons floods the entire selectron grid, the next element beyond the accelerating grid. The selectron grid, is made up of a number of thin bars located in a circular array, pointing radially outward, and a number of thin rings, spaced the same distance apart as are the bars. Figure 2 shows a portion of the selectron grid formed by the rings and bars. The rings and bars together form a number of little rectangular openings or windows.

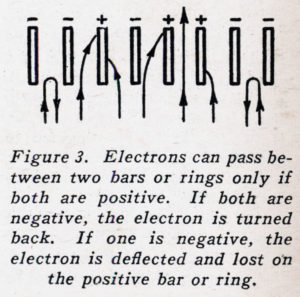

Now, in operation each bar and ring of the selectron grid is held either several hundred volts positive with respect to the cathode, or else a little negative with respect to the cathode. After a definite pattern of ages has been established on the selectron grid, the accelerating grid is made positive and the selectron grid is flooded with electrons. What happens? Let us consider first the bars of the selectron grid. Figure 3 tells the story. If two neighboring bars are negative, the approaching electrons are simply repelled and turned back. If an electron enters the space between a positive bar and a negative bar, it is so strongly attracted toward the positive bar that it strikes it and is lost. Only if the bars on both sides of the space which the electron enters are positive does the electron get through. At the rings, the story is the same; an electron can pass between two rings only if both are positive; it is stopped if either one or both are negative. Thus we conclude that electrons can pass through a little window formed by two bars and two rings only if both bars and both rings are positive. If both bars and both rings forming a window are held positive, the window is open; if one or more of the bars or rings are negative, the window is closed. Thus, we have a means for letting electrons through one window at a time.

Now, in operation each bar and ring of the selectron grid is held either several hundred volts positive with respect to the cathode, or else a little negative with respect to the cathode. After a definite pattern of ages has been established on the selectron grid, the accelerating grid is made positive and the selectron grid is flooded with electrons. What happens? Let us consider first the bars of the selectron grid. Figure 3 tells the story. If two neighboring bars are negative, the approaching electrons are simply repelled and turned back. If an electron enters the space between a positive bar and a negative bar, it is so strongly attracted toward the positive bar that it strikes it and is lost. Only if the bars on both sides of the space which the electron enters are positive does the electron get through. At the rings, the story is the same; an electron can pass between two rings only if both are positive; it is stopped if either one or both are negative. Thus we conclude that electrons can pass through a little window formed by two bars and two rings only if both bars and both rings are positive. If both bars and both rings forming a window are held positive, the window is open; if one or more of the bars or rings are negative, the window is closed. Thus, we have a means for letting electrons through one window at a time.

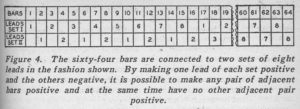

In the early model selectrons there were sixty-four apertures between bars around the tube, and sixty-four apertures lengthwise, giving four thousand ninety-six windows in all, and any one of these could be selected for the passage of electrons by applying proper voltages to the bars and rings. Does this mean that we must have one hundred twenty-eight leads into the tube for this alone, one for each bar and one for each ring? The tube would certainly work if it had one hundred twenty-eight leads to the selectron grid, but Dr. Rajchman’s ingenuity has cut this down instead to thirty-two, a saving by a factor of four. How is this done? The table of Figure 4 tells the story. Here we have in the top row the numbers of the bars, in order, sixty-four in all. These bars are connected to two sets of eight leads. The second and third rows show to which lead of a given set a bar is connected. Thus, Bar 1 is connected to Lead 1 of Set I. Bar 2 is connected to Lead 1 of Set II, while Bar 64 is connected to Lead 8 of Set II. To save space, some of the bars have been omitted from the table.

In the early model selectrons there were sixty-four apertures between bars around the tube, and sixty-four apertures lengthwise, giving four thousand ninety-six windows in all, and any one of these could be selected for the passage of electrons by applying proper voltages to the bars and rings. Does this mean that we must have one hundred twenty-eight leads into the tube for this alone, one for each bar and one for each ring? The tube would certainly work if it had one hundred twenty-eight leads to the selectron grid, but Dr. Rajchman’s ingenuity has cut this down instead to thirty-two, a saving by a factor of four. How is this done? The table of Figure 4 tells the story. Here we have in the top row the numbers of the bars, in order, sixty-four in all. These bars are connected to two sets of eight leads. The second and third rows show to which lead of a given set a bar is connected. Thus, Bar 1 is connected to Lead 1 of Set I. Bar 2 is connected to Lead 1 of Set II, while Bar 64 is connected to Lead 8 of Set II. To save space, some of the bars have been omitted from the table.

You will observe that if we make Lead 7 of Set I positive, and all the rest of the leads of Set I negative, Bars 13, 29, 45 and 61 will be positive. Then, if we make Lead 2 of Set II positive and all the other leads of Set II negative Bars 4, 8, 12 and 16 will be positive. All the bars which do not appear in either of the above listings will be negative. Now, the only adjacent bars listed are 12 and 13, which have been written in italics. Hence, when Lead 7 of Set I and Lead 2 of Set II are made positive and all the other leads negative, electrons can pass between the two adjacent positive bars 12 and 13, but not between any other bars. Thus, by selecting one lead from Set I and one lead from Set II, we can select any of the sixty-four spaces between bars.

You will observe that if we make Lead 7 of Set I positive, and all the rest of the leads of Set I negative, Bars 13, 29, 45 and 61 will be positive. Then, if we make Lead 2 of Set II positive and all the other leads of Set II negative Bars 4, 8, 12 and 16 will be positive. All the bars which do not appear in either of the above listings will be negative. Now, the only adjacent bars listed are 12 and 13, which have been written in italics. Hence, when Lead 7 of Set I and Lead 2 of Set II are made positive and all the other leads negative, electrons can pass between the two adjacent positive bars 12 and 13, but not between any other bars. Thus, by selecting one lead from Set I and one lead from Set II, we can select any of the sixty-four spaces between bars.

The thoughtful reader will have noticed, by the way, that there are only sixty-three spaces between sixty-four bars. This, however, omits the space out to infinity from Bar 1 and back from infinity to Bar 64. We can in effect shorten this space by adding an extra bar beyond the sixty-fourth and connecting it to Bar 1.

The same sort of connection used with the bars is made to the ring so that by selecting and making positive one lead each in two sets of eight leads we can select any of the sixty-four spaces between rings. Thus, in the end we have four sets of eight leads each, two sets the bars and two for the rings. We make positive one wire in each set at a time. The number of possible combinations we can get this way is four thousand ninety-six, and each allows electrons to go through just one window out of the four thousand ninety-six formed by the bars and rings of the selectron grid. The action is entirely positive. A given window is physically located in a given place. Small fluctuations in the voltages applied to the bars and rings will not interfere with the desired operation. This is a lot different from trying to locate a given spot by waving an electron beam around.

The selectron grid and its action are- of course, only a part of the mysteries of the selectron. They provide a means for directing a stream of electrons through one of several thousand little apertures at will. But, how can this stream of electrons be used in storing a signal and then in reading it off again? Part of the answer is not new. For some time electronic experts have n thinking of storing a signal on an insulating surface as an electric charge deposited on the surface by means of an electron stream. Thus, by putting electrons on a sheet of mica, for instance, we can make the surface negative, and by taking them off we can make it positive. It is easy enough to do either of these things, as we shall see in a moment.

There are two very serious difficulties with, such a scheme, however. First, how shall we keep the positive or negative charge on the insulating surface indefinitely? It will inevitably tend to leak off. Second, how can we determine whether the surface is charged positively or negatively without disturbing the charge? The logical exploring tool is an electron beam, but won’t the beam drain the charge off in the charge off in the very act of exploration? Both of these difficulties are overcome in the selectron. To understand how, we must know a little about secondary emission.

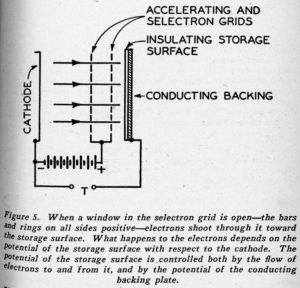

Beyond the accelerating and selectron grids of the selectron, as shown in Figure 1, there is a sheet of mica indicated as “storage surface.” This has a conducting backing. We are interested in what happens when electrons pass through an open window in the selectron grid – one made up of four positive bars and rings – and strike the mica. The essential ingredients of the situation are illustrated in the simplified drawing of Figure 5. Here the accelerating grid and the selectron grid are lumped together and shown as positive with respect to the cathode. Electrons are accelerated from the cathode, pass through the accelerating grid and the open window of the selectron grid, and shoot toward the mica storage surface. What happens? That depends on the potential of the storage surface with respect to the cathode.

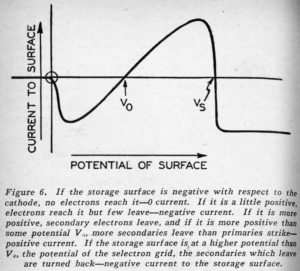

In Figure 6 the current reaching the part of the storage surface behind an open window is plotted vs. the potential of that part of the storage surface with respect to the cathode. Potential is negative with respect to the cathode to the left of the vertical axis and positive with respect to the cathode to the right of the vertical axis. Current to the storage surface is negative – electrons reaching the surface and sticking below the horizontal axis and positive – more electrons leaving the surface than reaching it – above the horizontal axis. The curve shows how current to the surface varies as the potential of the surface is varied.

In Figure 6 the current reaching the part of the storage surface behind an open window is plotted vs. the potential of that part of the storage surface with respect to the cathode. Potential is negative with respect to the cathode to the left of the vertical axis and positive with respect to the cathode to the right of the vertical axis. Current to the storage surface is negative – electrons reaching the surface and sticking below the horizontal axis and positive – more electrons leaving the surface than reaching it – above the horizontal axis. The curve shows how current to the surface varies as the potential of the surface is varied.

If the surface is negative with respect to the cathode, the electrons shot toward it are turned back before they reach it and the current to the surface is zero. If the surface is just a little positive, the electrons shot toward it are slowed down by the retarding field between the very positive selectron grid and the much less positive storage surface, and they strike the surface feebly and stick, constituting a negative-current flow to the surface, and tending to make the surface more negative. If the potential of the storage surface is a little more positive with respect to the cathode, the electrons reach it with enough energy to knock a few electrons out of it. These are whisked away to the more positive selectron grid. These negative electrons leaving the surface are equivalent to a positive current to the surface. There are now as many electrons striking as before, but there are also some leaving, and there is less net negative current to the surface. Finally, at some potential labeled V0 in Figure 6, one secondary electron is driven from the surface for each primary electron which strikes it, and the net current to the surface is zero. If the potential of the storage surface is higher than V0, each primary electron releases more than one secondary and there is a net flow of electrons away from the surface, equivalent to a positive current to the surface. This tends to make the storage surface more positive.

If the surface is negative with respect to the cathode, the electrons shot toward it are turned back before they reach it and the current to the surface is zero. If the surface is just a little positive, the electrons shot toward it are slowed down by the retarding field between the very positive selectron grid and the much less positive storage surface, and they strike the surface feebly and stick, constituting a negative-current flow to the surface, and tending to make the surface more negative. If the potential of the storage surface is a little more positive with respect to the cathode, the electrons reach it with enough energy to knock a few electrons out of it. These are whisked away to the more positive selectron grid. These negative electrons leaving the surface are equivalent to a positive current to the surface. There are now as many electrons striking as before, but there are also some leaving, and there is less net negative current to the surface. Finally, at some potential labeled V0 in Figure 6, one secondary electron is driven from the surface for each primary electron which strikes it, and the net current to the surface is zero. If the potential of the storage surface is higher than V0, each primary electron releases more than one secondary and there is a net flow of electrons away from the surface, equivalent to a positive current to the surface. This tends to make the storage surface more positive.

As the potential of the storage surface rises further above V0, current for a time becomes more and more positive. Then, abruptly the neighborhood of the potential VS of the selectron grid itself, the current becomes negative again and stays negative. Why is this? The the primary electrons still strike the storage surface energetically and drive out more than one electron each. The fact is that these secondary electrons leave the surface with very little speed. When the storage surface is more positive than the selectron grid, there is a retarding field at the storage surface which tends to turn the secondaries back toward the storage surface. Hence, there, is still a flow of primaries – a negative current – to the surface, but the secondaries are turned back before reaching the selectron grid and fall on the storage surface again. Thus, the current to the storage surface is again negative.

Our mechanism for holding the storage surface positive or negative is immediately apparent from Figure 6. If the surface is more positive than Vs, the current to it is negative and its potential will tend to fall. If the surface has a potential between V0 and Vs, the current to it is positive and its potential will tend to rise. Hence, if the storage surface initially has any potential higher than V0, current will flow to it in such a way as to tend to make its potential VB, the potential of the selectron grid. If, on the other hand, the potential is between O and V0, the current to the surface will be negative and the potential of the surface will tend to fall to O. If the potential of the surface is negative with respect to the cathode – less than O – there is no current to it from the electron stream and hence no tendency for the potential to rise and fall. Actually, some leakage would probably result in 3 very slight tendency for the potential to rise.

We see, then, that when it is bombarded by electrons, a part of the storage surface tends naturally to assume one of two potentials, or VS O. If it has initially any other potential, it tends to come back to one of these. Which potential it assumes is determined by whether the initial potential is greater or less than V0. Thus, if we store information on the part of the storage surface behind a particular window by making this area have a potential Vs with respect to the cathode – meaning, say, 1 – or O – meaning, O – and if this potential changes a little through electrical leakage, perhaps adjacent portions at a different potential, we can recover or regenerate the original potential merely by opening the window of the selectron grid and flooding the area with electrons. In fact, we can periodically regenerate the potentials behind all windows by opening all windows at once and flooding the whole surface with electrons. This is what is done in the operation of the selectron, and this regenerative feature, which makes it possible to retain the stored information indefinitely despite electrical leakage, is one of the most ingenious and important features of the selectron.

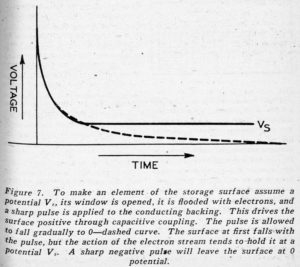

How do we get the information on the portions of the storage surface beind the various windows? That is, how do we initially bring some portions of the surface to the potential Vs and others to the potential V0? In this process of writing inflation into the tube, we first open the particular one of the four thousand ninety-six windows behind which we wish to store a particular piece of information, thus flooding a little portion of the surface with electrons. Then, to the terminals T of Figure 5, between the cathode and the conducting backstage of the storage surface, we apply a very sharply rising positive pulse, shown as the dashed line of Figure 7. Because of the capacitance between this backing plate and the front of the storage surface, where the electrons fall, this drives the front of the storage surface positive. Then the pulse applied to the conducting backing falls slowly to zero, as shown. However, the action of the electrons falling on the surface tends to make it assume the potential Vs, and so if the pulse falls off slowly enough the portion of the surface on which electrons fall is left at the potential Vs, as shown by the solid line of Figure 7. Application of the pulse will leave the portion of the storage surface behind the open window at the potential Vs regardless of whether its initial potential is Vs or O, and the pulse will not affect portions of the surface behind closed windows, because no electrons reach them.

This tells us how we can bring any selected area of the storage surface to the potential Vs which, we can say, corresponds to writing 1 in a particular cell of this memory tube. By flooding a given area or cell with electrons and applying a sharply falling, negative pulse, which rises again gradually toward O – the dashed pulse of Figure 7 upside down – we can bring any selected area of the storage surface to O potential, and thus write O in any selected cell of the memory.

This tells us how we can bring any selected area of the storage surface to the potential Vs which, we can say, corresponds to writing 1 in a particular cell of this memory tube. By flooding a given area or cell with electrons and applying a sharply falling, negative pulse, which rises again gradually toward O – the dashed pulse of Figure 7 upside down – we can bring any selected area of the storage surface to O potential, and thus write O in any selected cell of the memory.

Thus, each little area of the storage surface behind each window of the selectron grid is a cell of our memory. By opening a particular window – through making one lead of each of the four sets of eight selectron grid leads positive – and pulsing the conducting backing positive or negative, we can make the little area of the storage surface behind that window assume a potential Vs or a potential O, and so can, in effect, write 1 or 0 in that particular memory cell. By opening all windows periodically and flooding all areas with electrons, we can periodically bring all little areas back to their proper potentials, either VS or O, despite leakage of electrons to or away from the little areas. We can, that is, put thousands of pieces of information into the selectron and keep them there. What about reading? How can we get this information out?

Imagine that the entire inner storage surface is covered with a phosphor or fluorescent material like that used on cathode-ray tube screens or inside of fluorescent lights. Now, suppose we open one window of the selectron, shooting electrons at a particular area of the surface. If that area has a potential O, the electrons will be repelled from it. But, if that area has a potential Vs, corresponding to 1, the electrons will strike the fluorescent surface vigorously, emitting a glow of blue light. Suppose we let this light fall on a photo-multiplier, of the type Dr. Rajchman worked on earlier in his career. Then, when we open a given window of the selectron, if the potential of the surface behind the window is O, we get nothing out of the multiplier. But, if the potential is Vs, there is a flash of light, and a pulse of current from the multiplier. And so, we can not only write a O or a 1 in each little memory cell of the selectron, we can not only keep this information there indefinitely, but we can also read it off at will.

Dr. Rajchman has devised other ways for reading the stored information in the selectron, but the use of a phosphor-coated storage surface together with a photo-multiplier has been one of the preferred method. I have spoken of the phosphor as one giving blue light. This is because the photo-multiplier is more sensitive to blue light than to other colors. And so, I predicted that the memory cells of the thinking machines will be not only multitudinous and small, but also blue.

Of course the selectron provides only a part of the thinking machine – that is, the memory. Associated with it there must be circuits in tubes to seek out stored in tubes to seek out stored information, to make use of it to obtain new formation, to write in that new information, and to make use of the new information in turn. All is a field apart. Still, there is one wrinkle which is so intimately connected with the use of the selectron that it deserves mention here. I have referred to the O or 1 a cell of the selectron which can tore a binary digit or, alternately, as a letter of the electronic alphabet which the machine understands. Now, usually we don’t want to store isolated digits or letters: we want to store complete numbers or words – combinations of 1 and O, as, 10011. This is 19 in binary notation, and might in some instance stand for the nineteenth word in a dictionary. When we look up a number or a word, we want it all at once, not piecemeal.

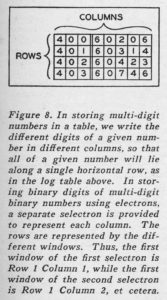

When we want to write many multi-digit numbers in a book, as, in a table of logarithms, for instance, we usually assign a vertical column for each digit to be stored, and write each digit of a given number in a different column, along the same row. Thus, entries in a log table appear as in Figure 8. Suppose that in using the selectron we assign a different tube to each binary digit of the numbers to be stored. If we wish to store twenty-digit numbers, we will need twenty tubes. Each tube will, in effect, be a given column of our storage space. The different cells in a tube will represent different rows. Thus, Cell 1 of Tube 1 will be Row 1 Column 1, Cell 1 of Tube 2 will be Row 1 Column 2, while Cell 10 of Tube 1 will be Row 10 Column 1, et cetera.

We want to look up all the digits in a given row at once. This means that we want to open corresponding windows in all the tubes at once, and so we can connect the corresponding selectron grid leads of all twenty tubes together. Thus, if want to store a number in Row 1, we apply voltages to the selectron grid leads which will open Window 1 in all tubes. We are then ready to read the number in Row 1 or to write a new number in. The twenty photo-multipliers which read the twenty selectrons are not connected in parallel, but are connected separately to carry off the twenty digits of the number in Row 1 to their proper destinations. Perhaps these twenty leads from the twenty photo-multipliers may go to the twenty backing plates of another twenty selectrons to which it is desired to transfer the number. We see, thus, how a whole table of numbers can be stored in twenty selectrons. The windows 1, 2, 3 et cetera, can represent, for instance, the angle of which we want the sine. The first selectron can store the first digits of all the sines, the second selectron can store all the second digits, et cetera. The twenty digits of the sine of any angle – any window number – can be read off simultaneously from the photo-multipliers of the twenty selectrons.

We want to look up all the digits in a given row at once. This means that we want to open corresponding windows in all the tubes at once, and so we can connect the corresponding selectron grid leads of all twenty tubes together. Thus, if want to store a number in Row 1, we apply voltages to the selectron grid leads which will open Window 1 in all tubes. We are then ready to read the number in Row 1 or to write a new number in. The twenty photo-multipliers which read the twenty selectrons are not connected in parallel, but are connected separately to carry off the twenty digits of the number in Row 1 to their proper destinations. Perhaps these twenty leads from the twenty photo-multipliers may go to the twenty backing plates of another twenty selectrons to which it is desired to transfer the number. We see, thus, how a whole table of numbers can be stored in twenty selectrons. The windows 1, 2, 3 et cetera, can represent, for instance, the angle of which we want the sine. The first selectron can store the first digits of all the sines, the second selectron can store all the second digits, et cetera. The twenty digits of the sine of any angle – any window number – can be read off simultaneously from the photo-multipliers of the twenty selectrons.

The selectron isn’t perfect by any means. Perhaps it’s not even the final answer. At the moment, in its early form, it may be almost expensive as relays, but that’s partly because it’s new. It’s certainly great deal more compact than relays, a very great deal faster, and probably more reliable as well. It represents a first huge stride in the electronics of the thinking machine. Just how far it takes us is up to a lot of mathematicians, a lot of circuit gadgeteers, and, especially, to Dr. Jan A. Rajchman and RCA, to whom we must look for smaller, cheaper and better selectrons.

– J.J. Coupling, 1949 –

______________________________

______________________________

References

Dr. Jan A. Rajchman

Jan A. Rajchman (at Wikipedia)

Jan. A. Rajchman (at I.E.E.E. History)

J.J. Coupling (Dr. John R. Pierce)

J.J. Coupling (at Wikipedia)

J.J. Coupling (at Speculative Fiction Database)

Machine Hearing and the Legacy of John R. Pierce (at Cal Tech) (at CalTech.edu)

Creative Thinking, by John R. Pierce (at Tom Schneider’s “Molecular Information Theory and The Theory of Molecular Machines”)

Selectron Tube

Pierce, John R. (as J.J. Coupling), “The Little Blue Cells”, Astounding Science Fiction, 1949, Vol. 42, No. 6, February, 1949, pp. 85-99

Lamps & Tubes / Lampen & Röhren (Giorgio Basile’s website)

Selectron Tube (at Wikipedia)

RCA Selectron (at Charles Osborne’s “RCA Selectron.com” – superb and comprehensive website)

Почему фон Нейман верил в SELECTRON (“Pochemu fon Neyman Veril v Selectron”) (Why Von Neumann believed in the Selectron) (In Cyrillic)

Astounding Science Fiction

Analog Science Fiction and Fact (at Wikipedia)